Why self-appraisals may not be best way to judge job performance

Research shows women, workers of color rate themselves lower; manager ratings tend to mirror them if bosses read rankings before writing their own

Companies often rely on annual employee reviews to determine who gets promoted, who gets a raise, and who are the best candidates for layoffs. But research has shown the process can be influenced by factors other than job performance, such as gender and race.

A new paper examines how those two factors played out in worker performance ratings at a multinational company, particularly in cases where bosses got a chance to see employee self-evaluations before doing their own.

In such cases, manager scores closely correlated to how high or low employees had rated themselves, suggesting an “anchoring” effect. Overall, women and workers of color tended to give themselves lower marks. Women of color rated themselves the least favorably and got the lowest scores from managers.

Managers gave out lower scores across the board when they didn’t see employee self-appraisals beforehand.

The Gazette recently spoke with the paper’s co-author Iris Bohnet, Albert Pratt Professor of Business and Government and co-director of the Women and Public Policy Program at Harvard Kennedy School. In this edited conversation, Bohnet, a behavioral economist who studies gender, explains how gender and race appear to shape the way employees are assessed at work and what can be done about it.

Why were you interested in the dynamics of performance evaluations?

Most performance appraisal processes invite employees to evaluate themselves and then share those self-evaluations with their managers before managers make up their minds.

I was concerned about that process and have been for a long time.

There’s lots of research in behavioral science and in psychology suggesting that if you throw even a random number at somebody, that anchors people’s judgments. If we throw any information at evaluators during the performance appraisal process, it’s very likely that information is going to influence their decisions.

Assume you’re my manager, and we have a rating scale from one to 10. I give myself a seven, another person gives themselves a nine. You will be influenced by the seven and the nine. The question is how informative the seven and the nine really are.

Women and people of color tend to give themselves lower self-evaluations. We knew that going in. If we have reason to fear that people differ in their ability or willingness to shine the light on themselves, then we might bake inequity into the system by inviting people to share their self-evaluations.

“On the employee side, we do find that women give themselves low self-ratings, and in particular, women of color give themselves even lower ratings than white women.”

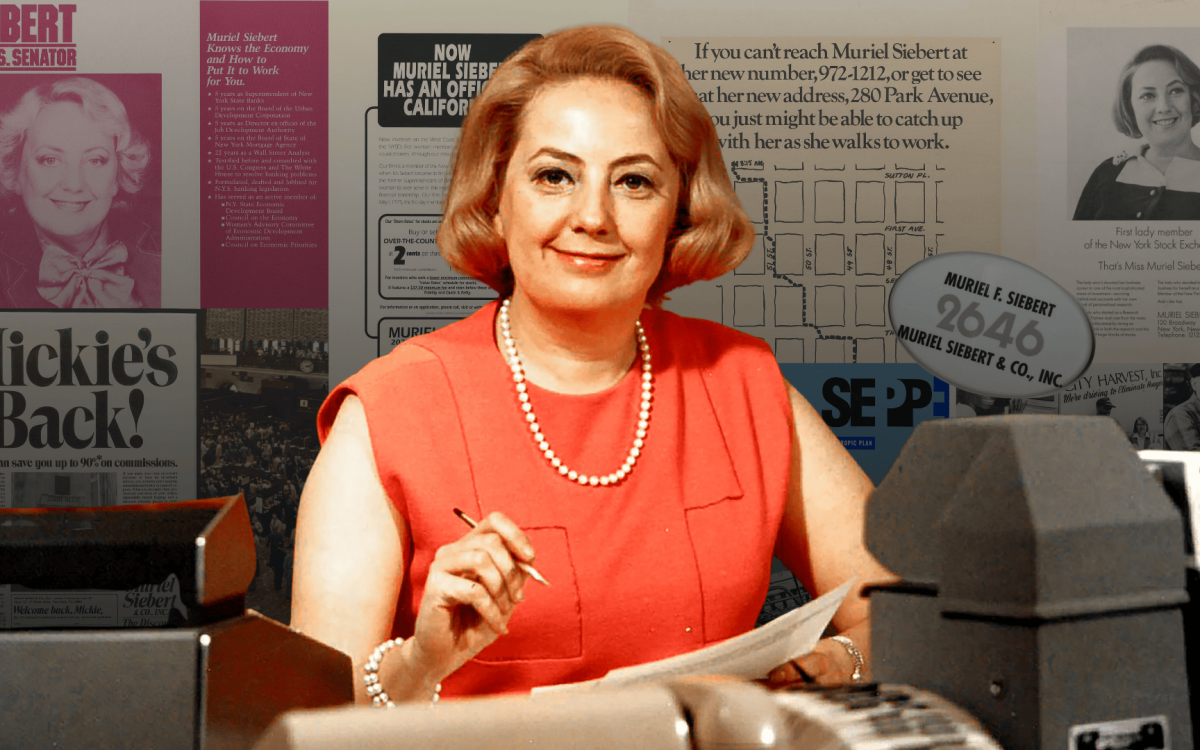

Iris Bohnet.

Photo by Martha Stewart

Overall, women received lower ratings than men, and employees of color were rated lower than white employees. Is that evidence of manager bias?

What we can say is certain outcomes are driven by the employees themselves; certain patterns are driven by managers.

On the employee side, we do find that women give themselves low self-ratings, and in particular, women of color give themselves even lower ratings than white women. I’m using the binary here on gender and race because these are global data.

Then, the question is what managers do with this information, and we see three patterns: The first one is they take everyone down. The second one is they take people of color down more than white people. And the third one is that they take women down less than men.

Somewhat surprising, we saw the employee-manager gap was less pronounced for all women. We don’t quite know why that is.

Something complicated happens on race.

There are two things happening for women of color. Remember, they started out giving themselves the lowest self-evaluations. Managers give them, so to speak, a gender “boost” — they decrease their evaluations less than those of men of color, for example. So, in that sense, they didn’t treat women of color any differently than white women.

However, this “boost” was not enough to correct for women of color’s very low self-evaluations.

What makes this even more complicated was that managers treated all people of color more harshly. So that’s where your question about manager bias comes in.

Is there anything that managers do in addition to what the self-evaluations are causing? Yes. The self-evaluation effect is driven by gender, and then the manager effect is driven by the reverse gender effect, and the fact that they evaluate people of color more harshly than white people, particularly, in the U.S., Black people.

We’re trying to be careful in the paper to say that the data do not allow us to prove that the observed patterns are due to bias.

It seems unlikely that people of color are worse performers than white people or that women of color should have given themselves worse ratings than everyone else. That’s what we told the company: “It’s not that we can prove this is biased because we don’t have objective performance information available. But the patterns are so correlated with social identities or demographic characteristics that this should probably give you pause.” Which it did.

During one of the years, managers did not get to look at employee self-evaluations before they submitted their performance reviews. Can you explain what happened?

Yes, the company had a glitch in the system that kept them from following their usual process. In that year, while they collected self-evaluations, they were unable to share them with managers beforehand. In the data, we see the glitch must have happened because the managers’ ratings are much less correlated with people’s self-evaluations.

We’re also seeing that managers lower people’s ratings even more than normally.

However, we were surprised that it didn’t change the gender-race dynamics. That glitch year, everything was lower, less correlated, and the dynamics looked like every other year. Which is why we looked at the data more carefully and then saw that managers must have gone back to the prior year’s self-evaluations. Their assessment is more correlated with what people did and said last year.

When I tell organizations, people are not very surprised that managers would do that. In some ways, it’s further support for this social influence channel. Managers really rely on these self-evaluations.

Your research focuses on interventions. Are there any that could minimize the social effects on managers while they conduct appraisals?

The financial services company decided to no longer share self-evaluations based on everything I just told you, including the caveats that we couldn’t show it as powerfully as we would have liked to show it.

They also decided to do the analysis that we did for them on a regular basis. These are data analyses that a data science team in a large firm can easily do and that helps them diagnose potential issues and to identify potential hotspots.

Not sharing self-evaluations might be helpful if managers don’t have access to an employee’s rating history. At least, this is what we found for newly hired employees in the glitch year, where women of color ended up with ratings on par with white women and men.

That doesn’t mean you can’t ask people to do self-evaluations and discuss them once managers have made up their mind.

While we did not study this ourselves, it could also be useful to give more evaluations rather than fewer.

Most firms have these appraisals once a year and that leads to lots of issues, including the social influence channel we have discussed, but also lobbying from employees that knock on the manager’s door the week before the process starts to influence their judgment and remind them of the wonderful things they have done this year. That leads to differences across all kinds of dimensions because some people are less likely to do that.

Culturally, it may not be appropriate to knock on your manager’s door. Or maybe gender comes in: For women, it’s harder to negotiate assertively in those types of instances. There are companies and organizations that have moved to quarterly evaluations to increase the accuracy of their performance assessments.

And then, secondly, more is better than less. Peer evaluations are intriguing, so it’s not just the manager and the employee, but other people as well. More accurate data that paints a more accurate picture of performance. It shouldn’t be only the manager, who might be very removed from what an employee does on a daily basis.

There are companies which have also done away with these performance appraisals completely and just decide to give feedback on a very regular basis, sometimes weekly, and find that much more productive than these formal evaluations.

But I fear the final verdict is still out. We need more organizations to take a close look at their data and test what works and what doesn’t to make these subjective performance appraisals more accurate and fairer.