Anxious about retirement savings? Avoid these mistakes.

Complexity of finance system sets up many for failure, argues economics professor

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

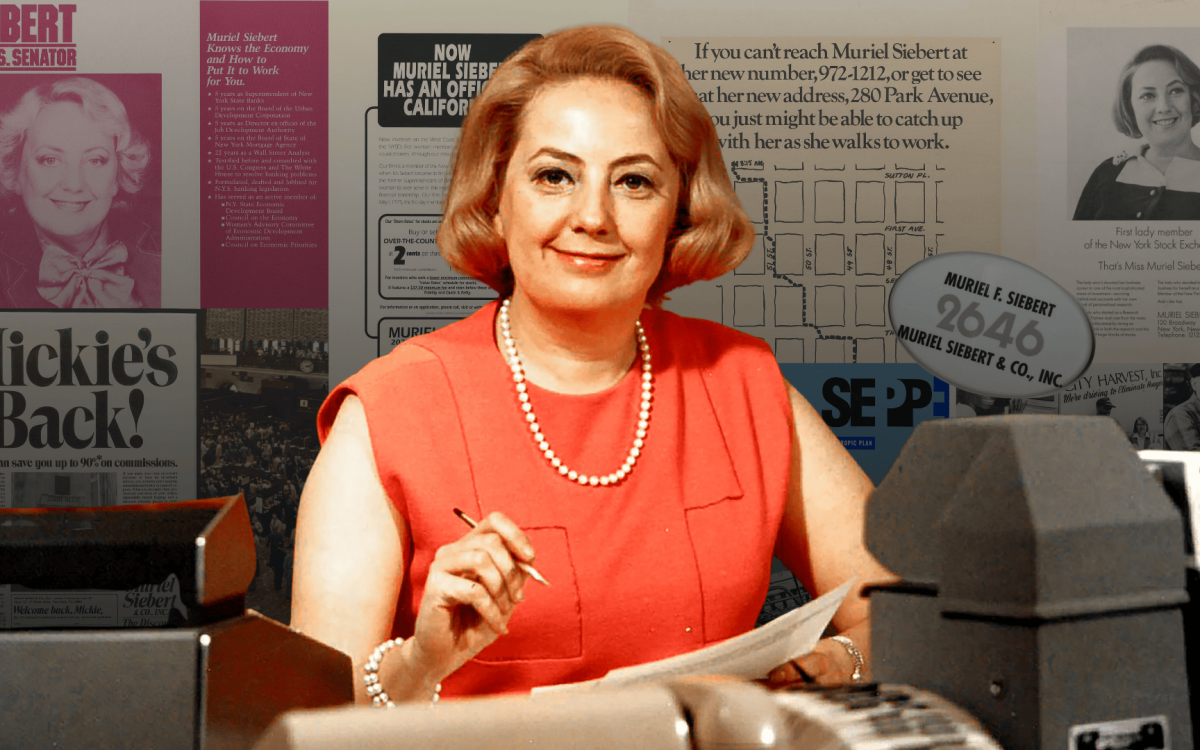

More than half of middle-income older adults in the U.S. believe that their savings won’t last them through retirement, according to findings published in November by the Pew Research Center. John Y. Campbell, the Morton L. and Carole S. Olshan Professor of Economics, isn’t surprised that people are worried.

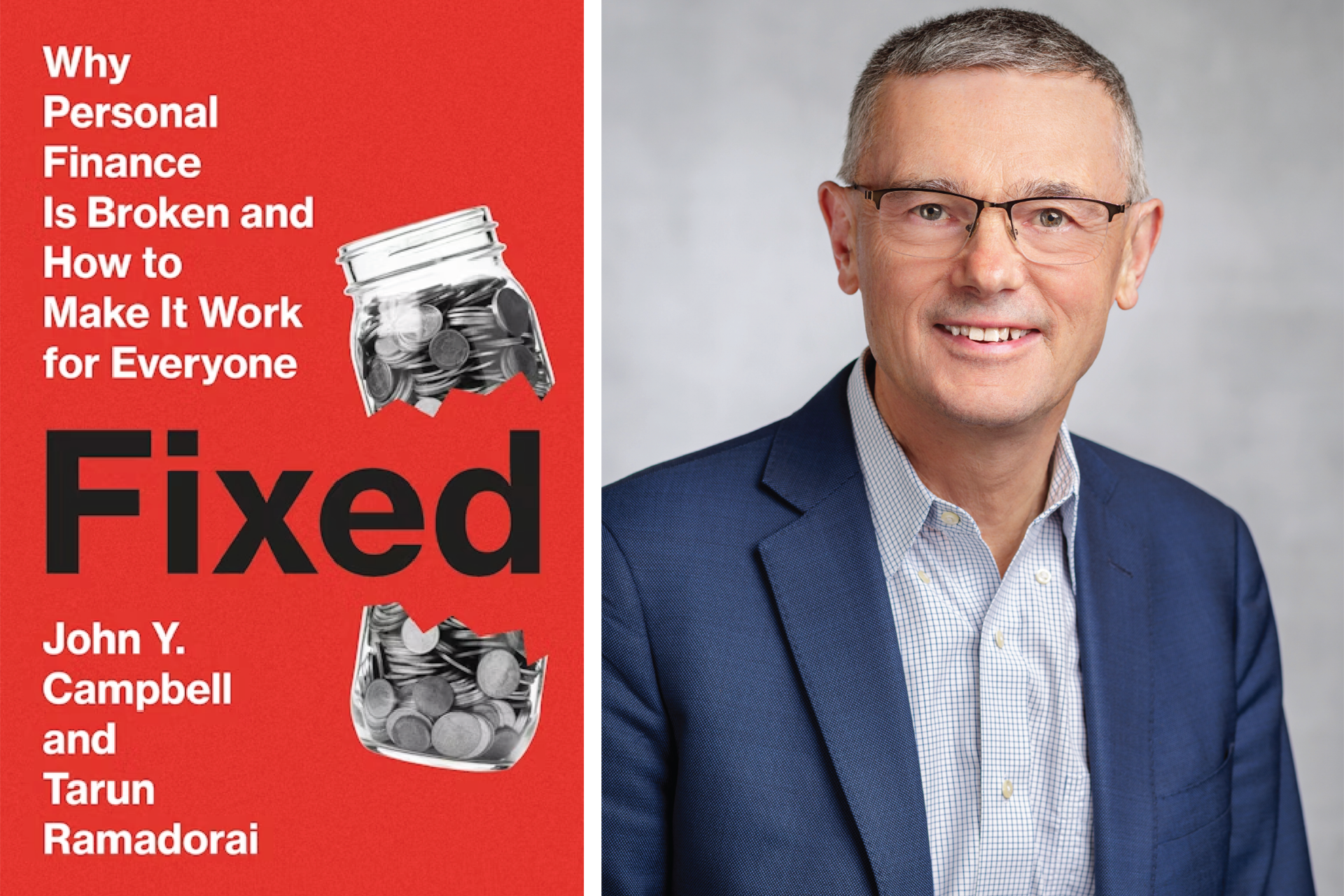

“What does concern me is that it’s not always the right people who are worried,” said Campbell, co-author of the new book “Fixed: Why Personal Finance is Broken and How to Make it Work for Everyone.”

In the book, Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai (Ph.D. ’03) of Imperial College London argue that the financial system acts as a “reverse Robin Hood,” setting the most vulnerable up for failure. In an interview edited for clarity and length, Campbell broke down the challenges of saving for retirement and what can be done to fix them.

Why is it so hard to save for retirement these days?

Life expectancy is high; if you retire at 65, you’re going to need to fund potentially decades of living expenses. A great many people underestimate how much they need to accumulate in a 401(k) or an IRA to fund a retirement of that length. People also tend to have smaller families and fewer people to rely on. And housing and higher education are so expensive — for many people going to college in this country, higher education imposes quite a debt burden on them, which makes saving for retirement much harder.

But there’s also a challenge that comes from the complexity of the financial system itself. If you feel confused and you don’t know what you’re doing, you naturally become very anxious. Unfortunately, one very natural human reaction is to ignore the problem, tell yourself you’ll deal with it later. That’s a very big mistake.

You argue in the book that the complexity of the financial system perpetuates inequality. How so?

Some inequality in the financial services sector is inevitable: For example, there are fixed costs to providing a financial service, and those fixed costs are going to be a bigger proportional drag on return for a small saver.

But there are also differences that arise because many financial products require skill to manage. If you’re unskilled, you’re going to make mistakes that generate fee revenue for the financial service providers. They may pocket some of that as profit, but they’re also competing for business, so part of that will get passed on in the form of lower prices up front.

As a result, if I know what I’m doing, I’m going to get a cheap product that’s only cheap because of the revenue that comes in from other people — often poorer, less-educated people — making mistakes.

Let me give you some examples. If you pay a late fee because you forgot to pay your credit card bill, that’s revenue the credit card company can then use to offer airline miles or cash-back rewards that savvier consumers benefit from. Or mortgages: Richer, better-educated consumers are more likely to refinance a fixed-rate mortgage at a beneficial time and end up paying much less over time. Essentially, it adds up to a reverse Robin Hood maneuver in which money is taken from poorer people and given to rich people.

It’s tempting to spend that extra $5 on a coffee instead of saving it for later. How much of the challenge of saving for retirement is caused by human psychology?

The challenge is really in the interaction between human psychology and the financial system. The market forces of capitalism meet the demand that’s being expressed, as opposed to the demand that would be expressed if people knew what they were doing.

But it’s not determinative. People hate to shop around for financial products because they find personal finance confusing, so they just stick with whatever bank they know. That’s a huge mistake. People can really alter their fortunes by just putting in a little more effort to look around. And of course you can make small changes like setting up some money to automatically transfer into savings from each paycheck.

“Essentially, it adds up to a reverse Robin Hood maneuver in which money is taken from poorer people and given to rich people.”

What are the consequences when the financial system does a poor job of setting people up for retirement?

As people have become aware of the inequalities, they’ve become very suspicious of financial institutions. Under these conditions, some people seek out alternatives to formal finance. They might keep their money under the mattress and miss out on earning interest; they might borrow from friends and family or turn to loan sharks; or they might invest in cryptocurrency. That’s jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire.

We need formal finance; it’s safer than the alternatives, and it funds investments in the future. That’s why we’re not revolutionaries: We want to reform the system and preserve traditional institutions.

You propose a financial “starter kit” to help people navigate the system. Can you explain that?

We push for a regulatory intervention to promote a set of straightforward, well-designed financial products that most people can start with.

An example might be access to 401(k) plans, which are currently available to people who work for large employers, but not so much for smaller employers and the self-employed. And when you move jobs, you may end up with multiple 401(k) plans that you have to remember to roll over into one another and so on.

Our starter kit would include a 401(k) plan that you’re offered when you work your first job, even if you’re a teenager bagging groceries at the supermarket, and it should carry with you for your lifetime. I would argue it should have a Roth structure, but that’s a technical detail. The main point is broader and simpler access to a retirement savings product for the retirement problem.

What are some practical ways to gauge the health of your retirement fund?

It’s always best to consult with a financial adviser. But as a rule of thumb, you want to retire with six years of income saved up. At 50, you should have about four years of income saved up, and plan to accumulate the remaining two years of income in the last 15 years or so of your working life.

But that number depends in part on the rate of return you can earn on that money, because in retirement, you’re not just spending the principal you’ve saved, but also the investment income. The inflation-indexed bond yield is a good proxy for a safe rate of return. For much of the 2010s and into the pandemic, that rate of return was zero or even negative, implying that you wouldn’t earn any safe investment return at all after correcting for inflation. Recently that has come up a lot, which is great news for investment savers. Now the inflation index bond yield is about 2 percent, which is about the historical average.

Many people do, and many people should, own significant stock investments as well. You can get a good idea of the long-term return on stock investments by looking at how expensive the stock market is in relation to earnings over 10 years, what’s called the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio. The record was 45 during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, and right now it’s at 40, the highest it’s been at any time since. So if you’re an aggressive stock investor trying to take some risks and get a higher return, this is a rather daunting environment, because stocks are so expensive. But if you’re a conservative bond investor just trying to keep your money safe, things are better than they were a couple of years ago.