Why are women twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s as men?

Andrzej Wojcicki/Getty Images

Researchers focusing on chromosomes, menopause

A neglected piece of the Alzheimer’s puzzle has been getting increased scientific attention: why women are twice as likely as men to develop the disease.

One might be tempted to explain the disparity as a natural consequence of women living longer. But those studying the disease say that wouldn’t account for such a large difference, and they’re not precisely sure what would.

While many factors may be at play, researchers are zeroing in on two where the biological differences between women and men are clear: chromosomes and menopause.

Women have two X chromosomes, and men have an X and a Y. Differences between genes held on the X and Y chromosomes, researchers say, may give women an increased chance of developing Alzheimer’s.

Menopause, when production of the hormones estrogen and progesterone declines, is another clear difference between the sexes. Those hormones are widely known for their roles in the reproductive system, but estrogen also acts on the brain, researchers say.

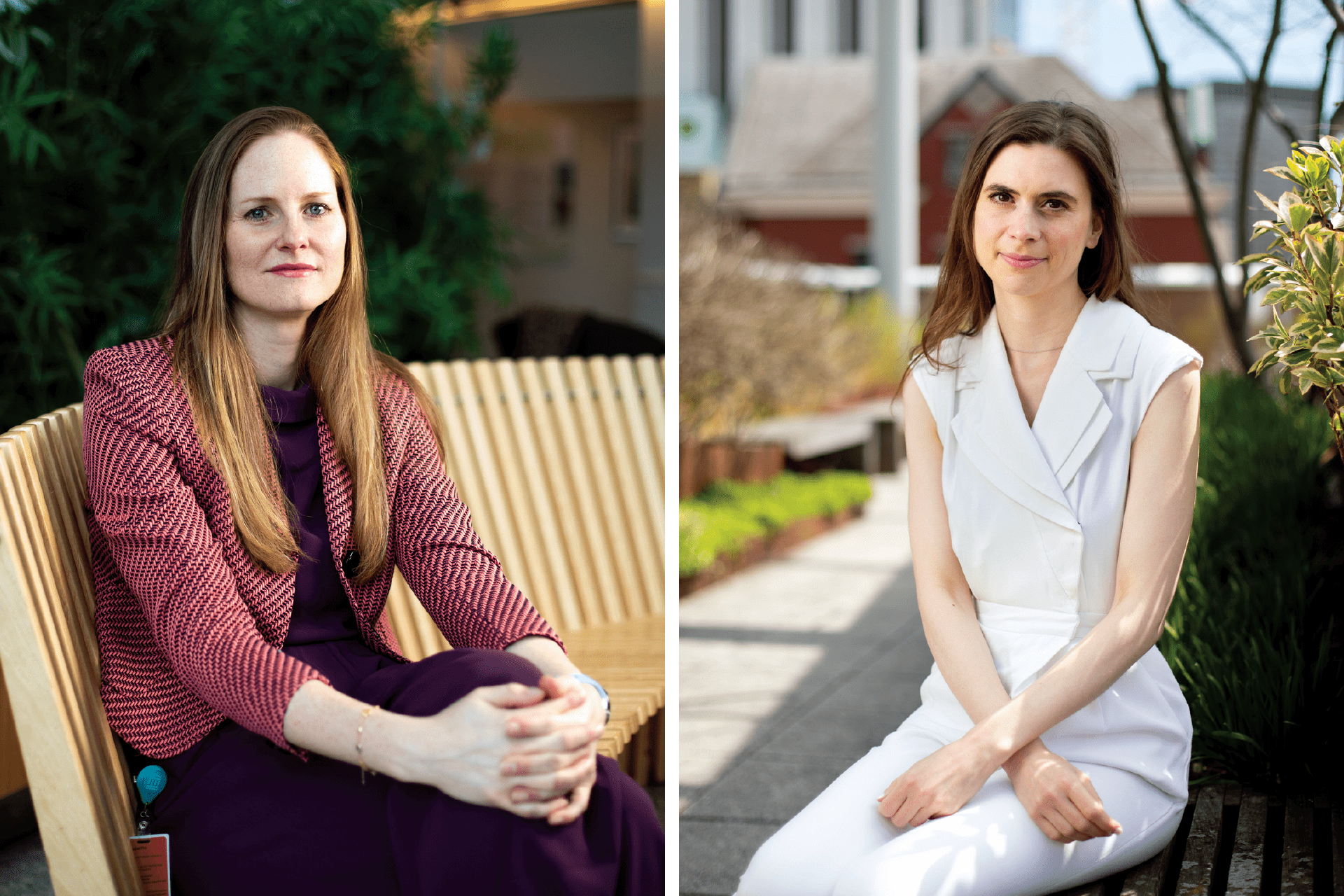

Researchers Rachel Buckley (left) and Anna Bonkhoff.

Photos by Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Whatever’s at play is likely part of deeper neurological processes, researchers say, pointing to similar sex-related differences in other conditions. Multiple sclerosis and migraine, for example, are both more common in women. Parkinson’s disease, brain tumors, and epilepsy, by contrast, are more common in men. In some cases — like migraine in women and Parkinson’s in men — increased severity accompanies increased incidence.

“Epidemiologically, we see that for almost all neurological diseases, there are differences in how many biological women and men are affected,” said Anna Bonkhoff, resident and research fellow in neurology at Harvard Medical School and Mass General Brigham. “There’s a tendency, for example, in MS and migraine for more females to be affected, while it’s the contrary for brain tumors and Parkinson’s. Just based on these numbers, you get the feeling that something needs to underlie these differences in terms of the biology.”

The basic building blocks are genes, which in humans are arranged on 46 chromosomes, organized into 23 pairs. One of those pairs — XX in women and XY in men — contain the genes that define sex-based characteristics, differences that are key areas of exploration.

The X and Y chromosomes differ significantly, Bonkhoff said.

The X chromosome is rich in genes, while the Y chromosome has lost a significant number over the millennia. Having two X chromosomes, though, doesn’t mean that women have a double dose of the proteins and other gene products produced by those genes, because one of the X chromosomes is silenced.

That silencing, however, is imperfect, Bonkhoff said, leaving some genes on the silenced X chromosome active. Studies have shown that genes on the X chromosome are related to the immune system, brain function, and Alzheimer’s disease.

“We know that biological men and women differ by the number of X chromosomes,” said Bonkhoff, lead author of a recent review article in the journal Science Advances that examined sex-related differences in Alzheimer’s disease and stroke.

“A lot of genes for the immune system and regulating brain structure are located on the X chromosome, so the dosages differ to certain degrees between men and women. That seems to have an effect.”

“If we can find ways to incorporate sex difference to optimize the treatment for individuals, both men and women, that is the overarching goal.”

Anna Bonkhoff

Another key difference between men and women relates to their hormones. All humans have three sex hormones: estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. In women, estrogen and progesterone dominate, while in men testosterone dominates. When one looks at changes between men and women with respect to hormones and aging, menopause is a significant nexus over the course of a lifetime.

“Menopause is part of the puzzle, probably one of the bigger ones,” Bonkhoff said. “I’m not saying it’s the only one — aging is relevant by itself, and there’s a lot of interesting research looking at what aging does to the immune system that seems to have implications for cognitive changes.”

Women typically go through menopause from their mid-40s to mid-50s. During that time, their ovaries stop producing estrogen and progesterone, resulting in the characteristic symptoms of menopause, like hot flashes, emotional changes, cessation of menstruation, difficulty sleeping, among others.

In March, Rachel Buckley, associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, and her colleagues followed that hormonal thread in a study that examined the impact of hormone replacement therapy and the accumulation of the protein tau in the brain, a key characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease.

Buckley, who is also an investigator in neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital, found that women who were receiving hormone replacement therapy later in life, after age 70, had significantly higher levels of tau accumulation, and suffered higher cognitive decline.

The result, she said, supports the “timing” approach to hormone therapy, which holds that hormone replacement therapy can safely be used to ease the symptoms of menopause, but should not be continued into old age.

The timing theory arose in response to a study by the federally funded Women’s Health Initiative in the early 2000s, which showed an association between women taking hormone replacement therapy and increased cognitive decline. That was contrary to expectations from earlier studies that indicated estrogen had protective effects on cognition.

Later studies, however, showed that hormone therapy appeared to be protective in younger women but was associated with declining cognition in women age 65 and up.

Buckley’s research took that work a step further, linking it to physiological changes in the brain. Alzheimer’s disease involves the accumulation of amyloid beta into characteristic plaques in the brain — considered an important hallmark of the condition. Those plaques spur the development of tangles of a protein called tau, which then sparks damaging inflammation.

Buckley’s research showed that hormone therapy among older women was associated with an increase in tau and with cognitive decline. It was not associated with an increase in amyloid beta, which today is a common therapeutic target.

“We’re trying to see if we can set up a new study design where we can really look at the time of menopause.”

Rachel Buckley

The research, published in the journal Science Advances in March and funded in part by the National Institute on Aging, allowed Buckley, Gillian Coughlan, first author and instructor in neurology, and their colleagues to highlight the role of hormone replacement in the accumulation of tau tangles in older women. But Buckley said the study also highlights significant areas where work remains to be done.

The database used for the study didn’t have information about variables that may be important, such as a woman’s reproductive history, information on when the replacement therapy was initiated, and the length of hormone therapy use.

Understanding the importance of that missing data, Buckley said, is a step forward even though the fact that it’s missing limits the conclusions that can be made in her study. To remedy that, Buckley is planning her own study that will gather what she believes is all the pertinent data, including reproductive history, and details of hormone therapy use.

“We work with a lot of secondary data that already exists, and that’s great but there are limitations to what we can do with it,” Buckley said. “We’re trying to see if we can set up a new study design where we can really look at the time of menopause, what is changing in the blood, what is changing in the brain, what is changing in cognition, and how that might be associated with later life risk.”

Sussing out how biological sex affects risk of Alzheimer’s disease, Bonkhoff and Buckley said, can help us understand Alzheimer’s more generally. That understanding, they said, has the potential to lead to new pathways of treatment and prevention of a disease that, despite decades of research and encouraging recent progress, is still poorly understood.

“It’s an important aim in medicine to understand and then to innovate in how we can prevent or treat,” Bonkhoff said. “If we can find ways to incorporate sex difference to optimize the treatment for individuals, both men and women, that is the overarching goal.”