‘Have a healthy respect that nature sometimes bites back’

It’s a bad year for ticks. Here are some precautions, and steps to take if you get bitten.

Getty Images

Public health officials are saying this year is a particularly bad one for ticks, due to milder winters and rainy springs in many parts of the country.

In a virtual event hosted by Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, experts from medicine, epidemiology, and environmental health came together to remind the public that these critters, which carry a range of serious diseases, can put a huge damper on summer plans if not taken seriously.

“Go outside. Enjoy nature, it’s healthy for you; but just have a healthy respect that nature sometimes bites back,” said Richard Pollack, senior environmental public health officer.

Gaurab Basu, an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Health, said it’s important to approach tick season thoughtfully, with rates of Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses on the rise.

“[We need] vigilance, not panic,” he said during the event, which was livestreamed July 1.

Basu said climate change has changed tick behavior and presence — essentially, they emerge earlier and remain longer. The arachnids are most active in warmer months, but there have been sightings even in January in some areas.

“We can’t say any one case of Lyme is because of climate change,” Basu said. “But we have to understand what we’re doing to our environment, what we’re doing by burning fossil fuels and warming our planet. And the trend lines that we are creating because of it.”

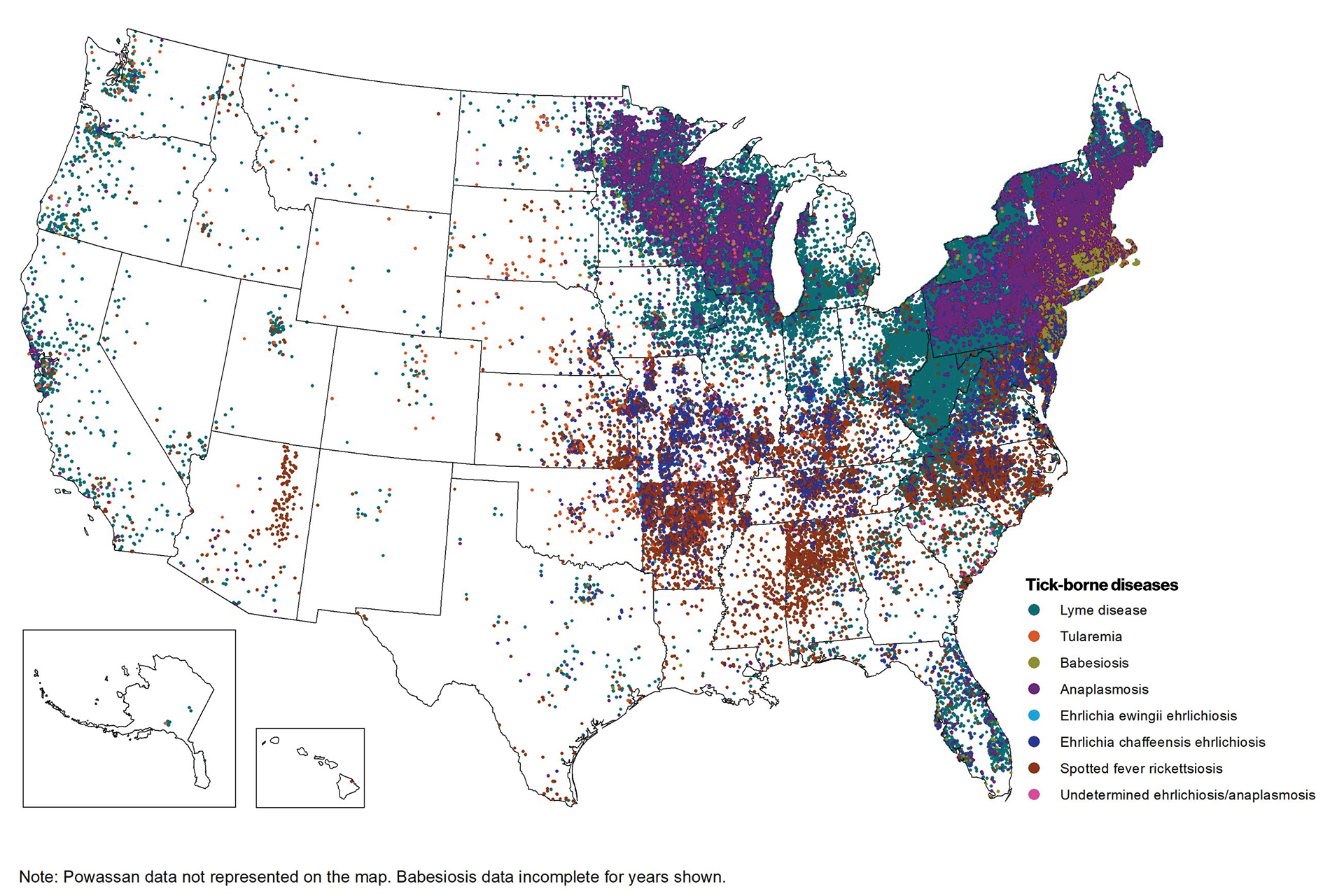

Previously known hot spots are still hot, particularly in New England and the Midwest, but the areas where ticks have thrived are growing.

Cassandra Pierre, assistant professor at Boston University’s Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine, said cases of tick-borne Rocky Mountain spotted fever are on the rise in southern Massachusetts, including places like Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard. While rare, it is a life-threatening disease if not recognized and treated early.

Reported cases of tick-borne diseases, 2019-2022

“Lyme certainly does still dwarf everything else we see,” Pierre said. That being said, she continued, instances of some of the rarer tickborne illnesses — like anaplasmosis and babesiosis — have increased.

A rise in co-infection rates, which track patients infected with multiple types of tick-borne diseases, complicates the picture even further. These cases can lead to more severe symptoms, delays in treatment, and prolonged illness.

Pollack shared basic best practices for keeping safe in high-risk outdoor areas.

When hiking, stay on the path; wear light-colored pants and socks so you can more easily spot a tick (Pollack encouraged listeners to flick the tick off and “send the tick for a ride”); pretreat clothing with an EPA-registered form of permethrin, a synthetic form of what can be extracted from chrysanthemums, which is known to be safe for humans; and use EPA-registered insect repellent on exposed skin.

Also check yourself occasionally while outdoors, and again when you come inside. If you find a tick, remove it immediately with a fine-tip forceps, your fingernail, or a credit card.

“Speed is far more important than is the actual means of removing,” Pollack said. “The longer the tick is attached, the more likely it is that it will be able to transmit one of those nasty pathogens to you.”

“When ticks attach, they need to attach for a period of 24-36 hours to have the opportunity to expose their host — in this case humans — to [pathogens],” said Pierre, who is also the medical director of public health programs and an associate hospital epidemiologist at Boston Medical Center. This is why checking frequently is crucial.

The antibiotic doxycycline is available by prescription and it can reduce the risk of infection by as much as 87 percent if taken within 72 hours of the bite.

At the end of the day, ticks are part of our natural environment, Pollack said.

“Nature is a core factor in human health and public health. You’ve got to respect nature, and I think we often don’t,” Basu said. “We need to integrate this understanding of how we build our communities, what kind of energy we use, where our roads are, where we’re building into. [These] all have profound implications for public health.”

The event was moderated by Dave Epstein, a meteorologist for WGBH and a correspondent for The Boston Globe. To watch the full event, visit the Chan School’s YouTube page. For more information on Lyme disease, visit the Lyme Wellness Initiative.