Tian Chen (T.C.) Zeng (from left) and David Reich.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Ancient DNA solves mystery of Hungarian, Finnish language family’s origins

Parent emerged over 4,000 years ago in Siberia, farther east than many thought, then rapidly spread west

Where did Europe’s distinct Uralic family of languages — which includes Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian — come from? New research puts their origins a lot farther east than many thought.

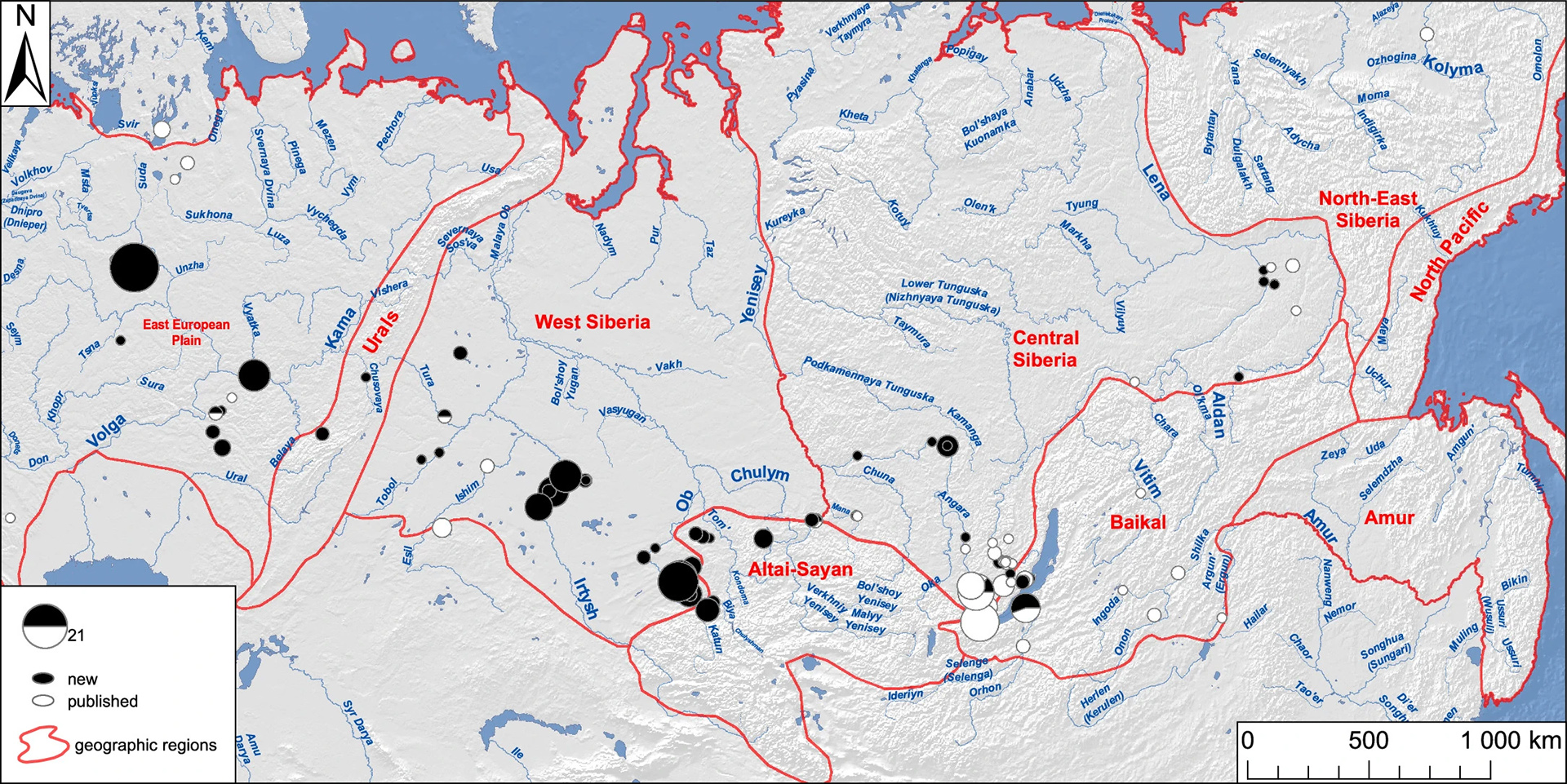

The analysis, led by a pair of recent graduates with oversight from ancient DNA expert David Reich, integrated genetic data on 180 newly sequenced Siberians with more than 1,000 existing samples covering many continents and about 11,000 years of human history. The results, published this month in the journal Nature, identify the prehistoric progenitors of two important language families, including Uralic, spoken today by more than 25 million people.

The study finds the ancestors of present-day Uralic speakers living about 4,500 years ago in northeastern Siberia, within an area now known as Yakutia.

“Geographically, it’s closer to Alaska or Japan than to Finland,” said co-lead author Alexander Mee-Woong Kim ’13, M.A. ’22.

Linguists and archaeologists have been split on the origins of Uralic languages. The mainstream school of thought put their homeland in the vicinity of the Ural Mountains, a range running north to south about 860 miles due east of Moscow. A minority view, noting convergences with Turkic and Mongolic languages, theorized a more easterly emergence.

“Our paper helps show that the latter scenario is more likely,” said co-lead author Tian Chen (T.C.) Zeng, who earned his Ph.D. in human evolutionary biology this spring from the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “We can see this genetic pulse coming from the east just as Uralic languages were expanding.”

The discovery was made possible by Kim’s long-term effort to gather ancient DNA data from some of Siberia’s under-sampled regions. As he helped establish, many modern-day Uralic-speaking populations carry the same genetic signature that first appeared, in unmixed form, in the 4,500-year-old samples from Yakutia. People from all other ethnolinguistic groups were found, by and large, to lack this distinct ancestry.

Genetic ties to Yakutia also show up in sets of hyper-mobile forager hunter-gatherers believed to have spread Uralic languages to northern Scandinavia’s indigenous Sámi people and as far south as Hungary, now a linguistic island surrounded by German, Slovak, and other Indo-European languages.

Proto-Uralic speakers overlapped in time with the Yamnaya, the culture of horseback herders credited with transmitting Indo-European across Eurasia’s grasslands. A pair of recent papers, led by Reich and others in his Harvard-based lab, zeroed in on the Yamnaya homeland, showing it was mostly likely within the current borders of Ukraine just over 5,000 years ago.

“We can see these waves going back and forth — and interacting — as these two major language families expanded,” offered Reich, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and human evolutionary biology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “Just as we see Yakutia ancestry moving east to west, our genetic data show Indo-Europeans spreading west to east.”

But Uralic’s influence was largely anchored in the north.

“We’re talking about taiga — the large expanse of boreal forest that goes from Scandinavia almost to the Bering Strait,” said Kim, who concentrated in organismic and evolutionary biology at the College and studied archaeology at the Harvard Griffin GSAS. “This isn’t territory you can simply ride a horse through.”

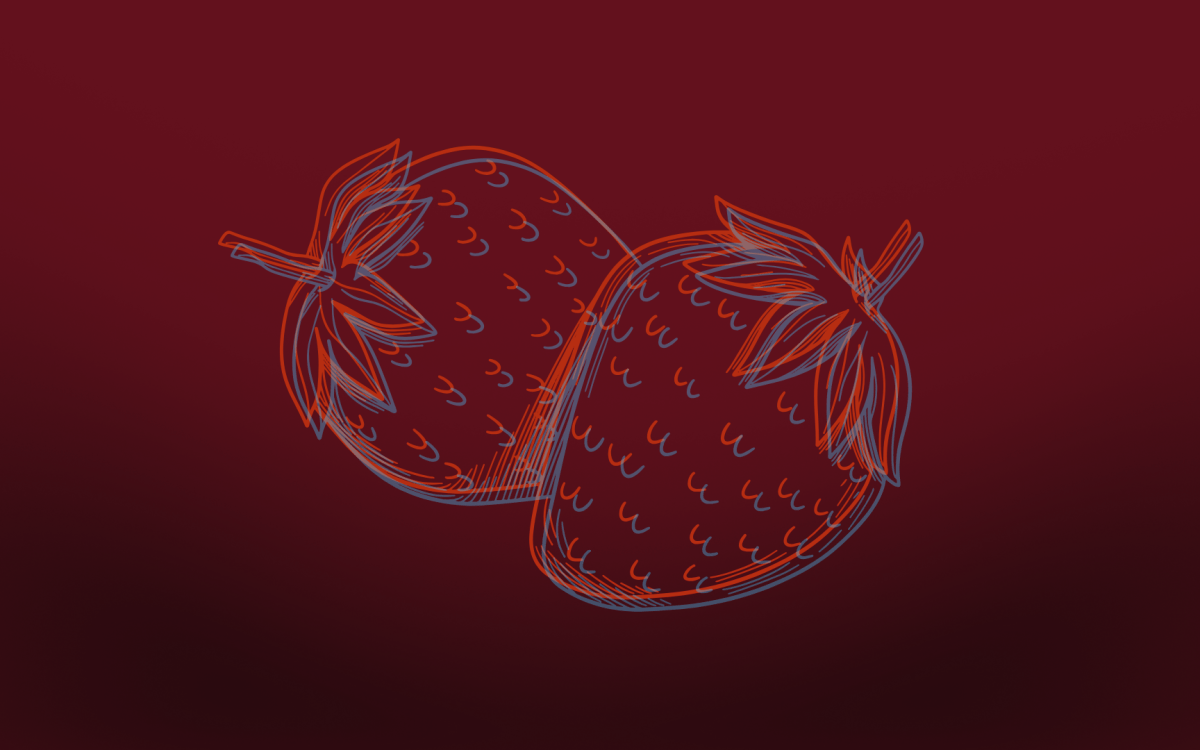

Archaeologists have long connected Uralic’s spread with what is called the Seima-Turbino phenomenon, or the sudden appearance around 4,000 years ago of technologically advanced bronze-casting methods across northern Eurasia.

The resulting artifacts, primarily weapons and other displays of power, have also been tied to an era of global climate changes that could have advantaged the small-scale cultures that spoke Uralic languages during and after the Seima-Turbino phenomenon.

Seima-Turbino artifacts.

Source: “Ancient DNA reveals the prehistory of the Uralic and Yeniseian peoples,” Nature

“Bronze often had a transformative effect on the cultures that used it,” explained Zeng, noting the need to source raw materials — largely copper and tin — from select locations. “Bronze really catalyzed long-distance trade. To start using it, societies really needed to develop new social connections and institutions.”

A picture of the genetically diverse communities who practiced Seima-Turbino techniques became clear with the advent of ancient DNA science.

“Some of them had genetic ancestry from Yakutia, some of them were Iranic, some of them were Baltic hunter-gatherers from Europe,” Reich said. “They’re all buried together at the same sites.”

The newest genetic samples, assembled by Kim with the help of other archaeologists, including third co-lead author Leonid Vyazov at Czechia’s University of Ostrava, revealed strong currents of Yakutia ancestry at a succession of ancient burial sites stretching gradually to the west, with each bearing rich reserves of Seima-Turbino objects.

“This is a story about the will, the agency of populations who were not numerically dominant in any way but were able to have continental-scale effects on language and culture,” said Kim, an archaeologist with longstanding interest in Siberia and Central Asia.

Map of all the sites that are sources of samples used in the study.

Source: “Ancient DNA reveals the prehistory of the Uralic and Yeniseian peoples,” Nature

Previous studies established that Finns, Estonians, and other Uralic-speaking populations today share an Eastern Eurasian genetic signature. Ancient DNA researchers ruled out the region’s best-known archaeological cultures from contributing to the Uralic expansion

“That just meant we needed more data on obscure cultures, or obscure time periods where it was unclear what was happening,” said Zeng, who led the study’s analyses of DNA data.

Today, he found, Uralic-speaking cultures vary in how much Yakutia ancestry they carry.

Estonians retain about 2 percent, Finns about 10. At the eastern end of the distribution, the Nganasan people — clustered at the northernmost tip of Russia — have close to 100 percent Yakutia ancestry. At the other extreme, modern-day Hungarians have lost nearly all of theirs.

“But we know, based on ancient DNA work from the medieval conquerors of Hungary, that the people who brought the language there did carry this ancestry,” Zeng emphasized.

A separate finding concerns another group of Siberian-spawned languages, once widely spoken across the region. The Yeniseian language family may be contracting today, with the last survivor being central Siberia’s critically endangered Ket, now spoken by just a handful of the culture’s elders. But Yeniseian’s influence was long evident to linguists and archaeologists alike.

“Just like ‘Mississippi’ and ‘Missouri’ are from Algonquian, there are Yeniseian toponyms in regions that today speak Mongolic or Turkic languages,” said Kim, a scholar on these languages since his undergraduate years (when he also learned to speak Uyghur). “When you consider this trace on the landscape, its influence extends far beyond where Yeniseian languages are spoken.”

The study locates the first speakers of the Yeniseian family some 5,400 years ago near the deep waters of Lake Baikal, its southern shores just a few hours by car from the current border with Mongolia.

The genetic findings also provide the first genetic signal — albeit a tentative one — for Western Washington University linguist Edward Vajda’s Dene-Yeniseian hypothesis, which proposed genealogical connections between Yeniseian and the Na-Dene family of North American Indigenous languages.

Research described in this report was supported by the National Institutes of Health as well as by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the John Templeton Foundation.