We know exercise is good for you. Why? He‘s working on it.

Building on decades of research, Robert Gerszten seeks to pinpoint movement’s molecular benefits

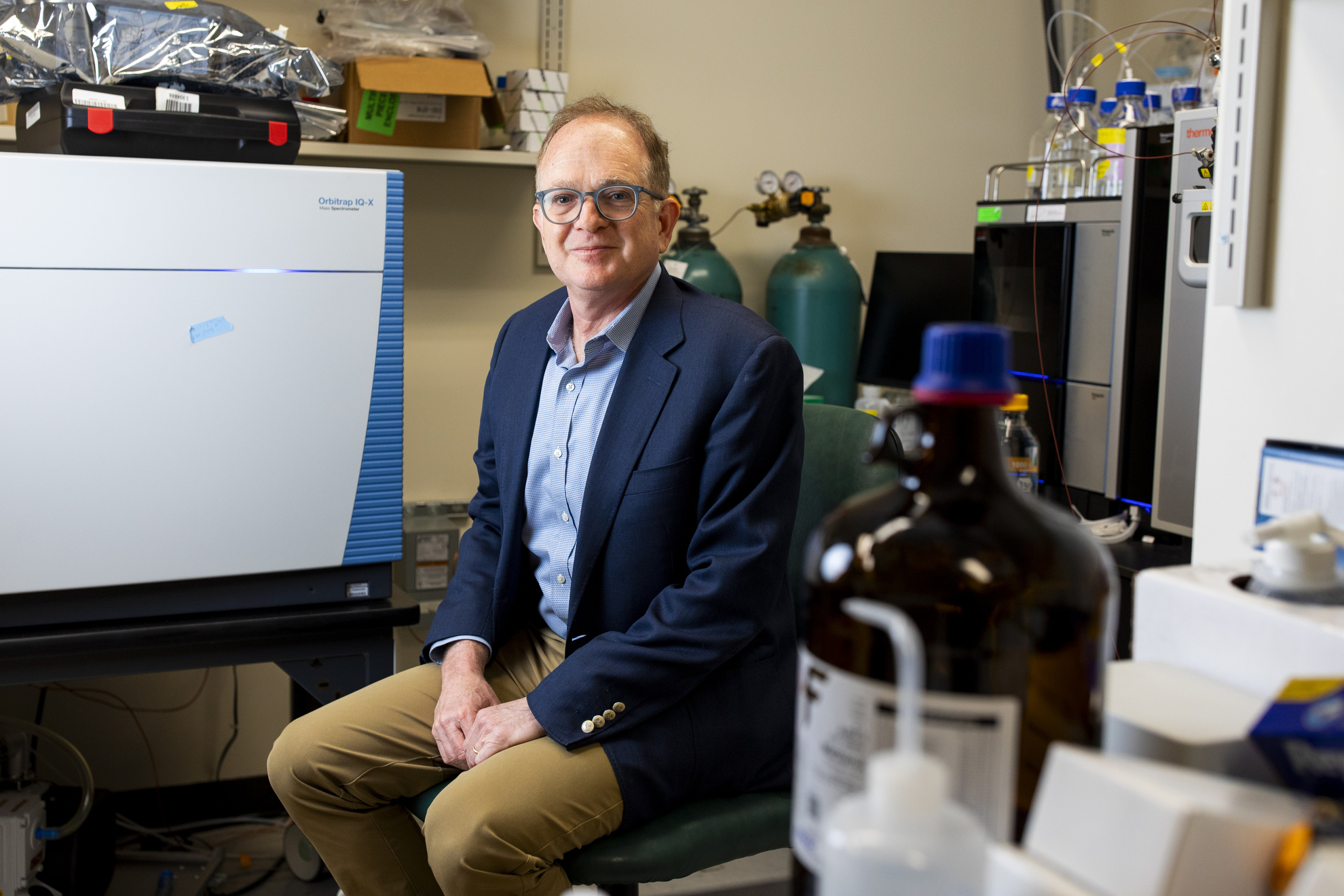

Robert Gerszten in his lab.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

We know exercise is good for us — but not exactly why. At Harvard, researchers are trying to pinpoint how exercise impacts our bodies down to the cellular level.

“It’s been known since Hippocrates that exercise is associated with health,” said Robert Gerszten, a professor at Harvard Medical School and chief of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. “But how exercise is beneficial at a molecular level is not well described.”

For decades, Gerszten’s lab has been tackling this question. Notably, he’s been involved in a landmark National Institutes of Health project launched in 1992 known as the HERITAGE Family Study. Drawing on data from more than 650 men and women of varying fitness levels undertaking a 20-week exercise program, the study continues to publish findings.

In 2021, Gerszten helped author a paper using HERITAGE data in which researchers were able to predict with reasonable accuracy whether individuals could improve their cardiovascular fitness, and by how much. The team used pioneering molecular tools to identify blood-based biomarkers linked to fitness and training response. Out of the more than 5,000 proteins his lab studied, Gerszten and his team were able to identify 147 that had strong predictive relationships.

“We began to identify some new biochemicals that hadn’t been described previously in the context of exercise physiology,” Gerszten said.

Building on that work, Gerszten is a part of another NIH-funded project — the Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium. His lab is one of the core chemical analysis sites analyzing clinical metrics like blood pressure, VO₂ max (a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness), and muscle strength in more than 2,000 participants. Additionally, the team is taking blood samples and tissue biopsies before and after 12 weeks of exercise to analyze molecular changes compared to baseline samples.

“The HERITAGE study was a prelude for this study,” Gerszten said. “It was the largest exercise study ever done, and it was about 650 people, so about a third of the size of this.”

“The notion is, if you identify some pathway that’s conferring a lot of the benefit of exercise, do you really need the exercise?”

Gerszten noted that this study isn’t comprehensive just because of its size, but also its breadth of patients. There are participants under 18 and over 60. And from each person, about seven blood samples are taken, along with tissue samples, during acute exercise. “Each time,” he said, “before and after training, you get muscle and fat biopsies.”

The researchers are seeking to better understand why some people respond better to different types of workouts, such as running versus weightlifting. They also hope their findings will lead to clinical applications.

“The notion is, if you identify some pathway that’s conferring a lot of the benefit of exercise, do you really need the exercise?” Gerszten said. “You can imagine that for certain individuals, wheelchair-bound, super frail, etc., these types of putative interventions might be particularly helpful.”

Early findings from pre-COVID trials of patients are starting to be released. Though Gerszten said it may be years before all the data is collected and analyzed, an unusual feature of the study is that data is being released publicly on a rolling basis to allow doctors and scientists to use it for their own research.

“This is one of the largest genomic databases,” Gerszten said. “So there’s going to be so many eyes on the data. I would underscore that the real goal is to get this out ASAP for everybody to look at.”

This research is supported by the NIH Common Fund and is managed by a program team led by the NIH Office of Strategic Coordination, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the National Institute on Aging, and by a trans-agency working group representing multiple NIH institutes and centers.