Harvard file photo

Marine vet’s future was a puzzle. Then he found archaeology.

Shane Rice credits Gen Ed class — and professor’s wall of declassified intelligence photos — with illuminating career path

Part of the Commencement 2025 series

A collection of features and profiles covering Harvard University’s 374th Commencement.

The professor’s office was wallpapered with declassified U.S. intelligence photos.

“I walked in and the first thing I saw were these floor-to-ceiling printouts of U2 and CORONA aerial imagery,” recalled Shane Rice ’25. “I took one look and thought — maybe there’s something here.”

Rice, 26, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, needed a new scholarly focus. When he first arrived at Harvard from Warrenton, Virginia, he had his sights set on environmental engineering. But the field proved a poor fit for his interests and talents. “So I went on this search,” he recalled. “I got lunch with all these different department heads including integrative bio and environmental science public policy.”

The quest ended in the office of Jason Ur, Stephen Phillips Professor of Archaeology and Ethnology, with its collection of aerial landscapes. The display resonated with Rice, in part due to his military training. As a mortarman, he frequently worked with maps and satellite imagery over three deployments.

Rice was drawn to Ur’s introductory “Can We Know Our Past?” course. The Cabot House resident, who settled into College life with the help of the Warrior-Scholar Project and other veteran supports, later won a prize for his essay on the clarity he gained during the Gen Ed offering.

The curriculum, he wrote, helped him reconcile a calling to public service with interests in antiquities, procedure, organizing data, and working in places far from home. “Shane wrote very eloquently about how studying archaeology helped him figure out the transition to academia from the military,” Ur said.

“Shane wrote very eloquently about how studying archaeology helped him figure out the transition to academia from the military.”

Jason Ur

Those Cold War-era stills that captivated Rice allow Ur to survey sites in Syria, Turkey, and Iran. Since 2012, the technique has helped Ur scour the Kurdistan region of Northern Iraq for traces of ancient atrocities. Rice became the rare undergraduate to join Ur’s fieldwork in the semi-autonomous region. He even applied Ur’s methods to an investigation of scars left far more recently in the area. Rice used declassified satellite reconnaissance to uncover hundreds of lost settlements, all destroyed during Iraq’s suppression of ethnic Kurds.

“In 1987, the Iraqi Army, under the regime of Saddam Hussein, cleared the entire plain where we’re working of its rural Kurdish villages,” Ur said. “The intensive mapping Shane did offers us a great analogy for understanding the distribution and density of rural settlements in the deeper past. But it also stands as a testament to genocidal state actions.”

Visiting Ur during weekly office hours became a new habit for Rice. That’s how he learned of the professor’s fieldwork around the city of Erbil, capital of the Kurdistan Region. Ur collaborates with researchers there to sift the area for features dating to the Neo-Assyrian Empire (ca. 900-600 B.C.)

“We’re there to test the hypothesis that the Assyrian kings engaged in large-scale deportation,” explained Ur, noting that the rulers’ accounts are corroborated by their victims in the Hebrew Bible.

Also pocking the region’s landscapes is evidence of recent demographic assaults. Hussein was eventually charged with killing tens of thousands of Kurds during the 1988 Anfal campaign. U.S. news coverage has often focused on the government’s use of chemical weapons against Kurdish civilians but less so on the destruction, a year earlier, of rural farming villages.

“We don’t think of the 1980s as being terribly archaeological,” said Ur, who helped Rice settle on these villages for his thesis topic. “But this was the same tragic story told 3,000 years after the Assyrians. And it really needed some dedicated work.”

Rice was invited to join Ur on the Erbil plain just before his junior year. “I choose my team very carefully, because we’re basically as an extension of American diplomacy when we’re there,” Ur said. “Shane impressed me early on with his extraordinary responsibility and discipline, which I’m sure comes from his military background.”

The archaeology concentrator had been toying with specializing in nomad pastoralists. Rice, who also completed a language citation in Russian, arrived in Erbil after spending weeks with reindeer herders in northern Mongolia. But Ur’s work in the Kurdistan Region felt far more urgent. “They’re racing against the clock with this project,” Rice said. “They’re racing against urban development and sprawl to try to document these sites.”

Upon returning to Cambridge, Rice immediately set about structuring his own research project. Foundational to his approach was Ur’s graduate-level course on archaeological applications of Geographical Information Systems. Rice started searching government databases that semester for declassified intelligence photos that fit his needs in terms of resolution, timescale, and coverage of the 3,000-square-kilometer survey area.

That’s how he discovered a cache of high-resolution landscape images, declassified in 2013, that were collected in June 1980 by the KH-9 Hexagon U.S. photo-reconnaissance satellite. “In a perfect world, you would compare photos taken right before and right after the point of impact,” Rice said. “But 1980 was pretty close to the time we were looking at.”

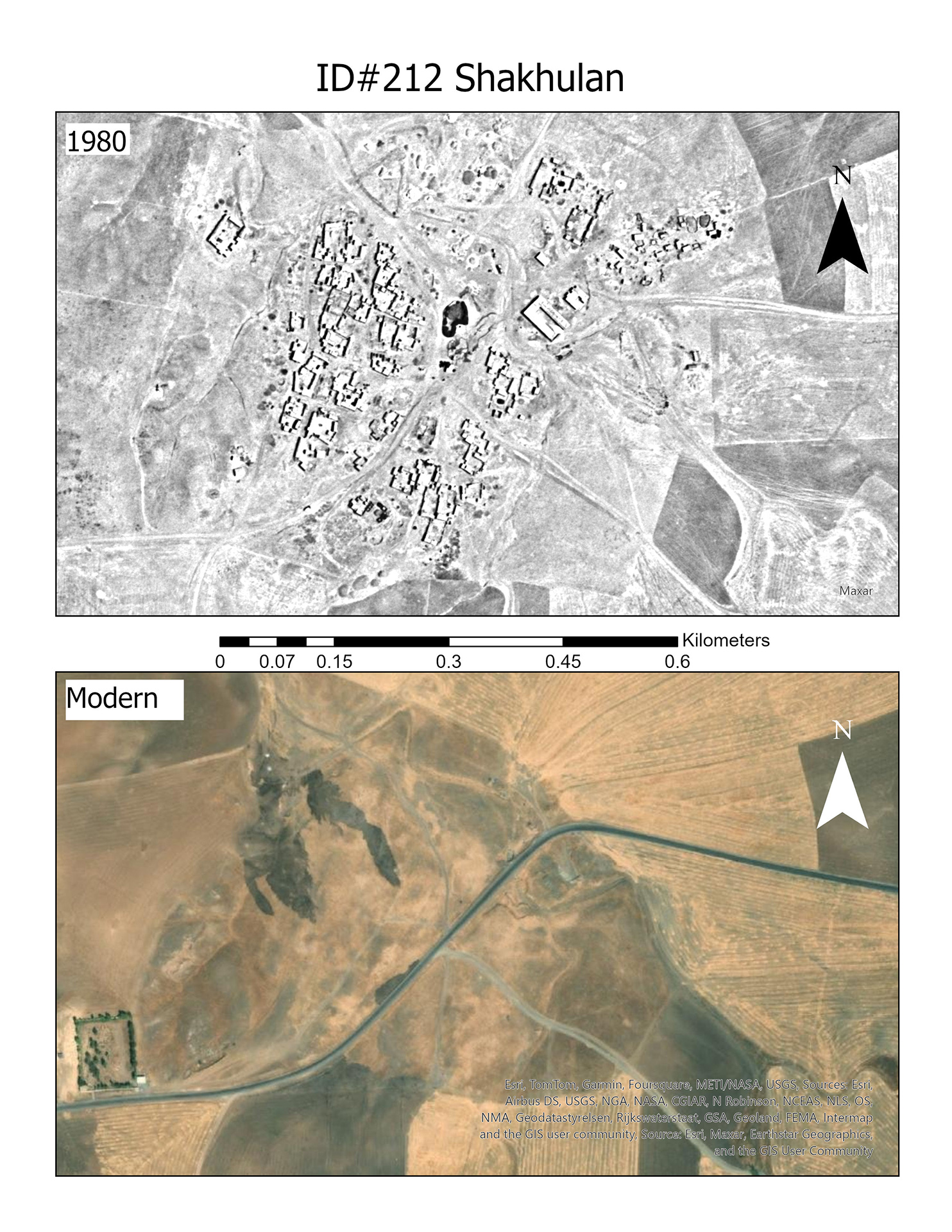

Matching these satellite captures to contemporary commercial imagery enabled Rice to document hundreds of destroyed settlements. The village of Shakhulan, he found, had been plowed over, appearing in modern images as little more than cultivated fields. Standing in place of other locales were new construction or ruins.

Rice compared images from 1980 and 2013 to document destroyed settlements in the Kurdish Region of Iraq.

Images courtesy of Shane Rice

“Sometimes there is literally the footprint of the four walls that once made a building,” Rice said.

The 1980 set also revealed a tightly gridded refugee complex, or mujamma’a, that matched one described in a 1993 Human Rights Watch report. By then, the undergraduate knew the history’s rough contours from his Kurdish collaborators and friends. The Anfal campaign followed years of the Iraqi military forcibly removing Kurds to tent camps like the one he identified 25 kilometers south of Erbil.

“These sites have existed purely in oral tradition and memory,” said Rice, who will begin at Cornell Law School in the fall. “And here we have primary-source evidence of one of these sites that thousands of individuals and families were moved through. To me, that speaks to the real value of doing this project.”