Finding common humanity, modern lessons in antiquity, a path forward

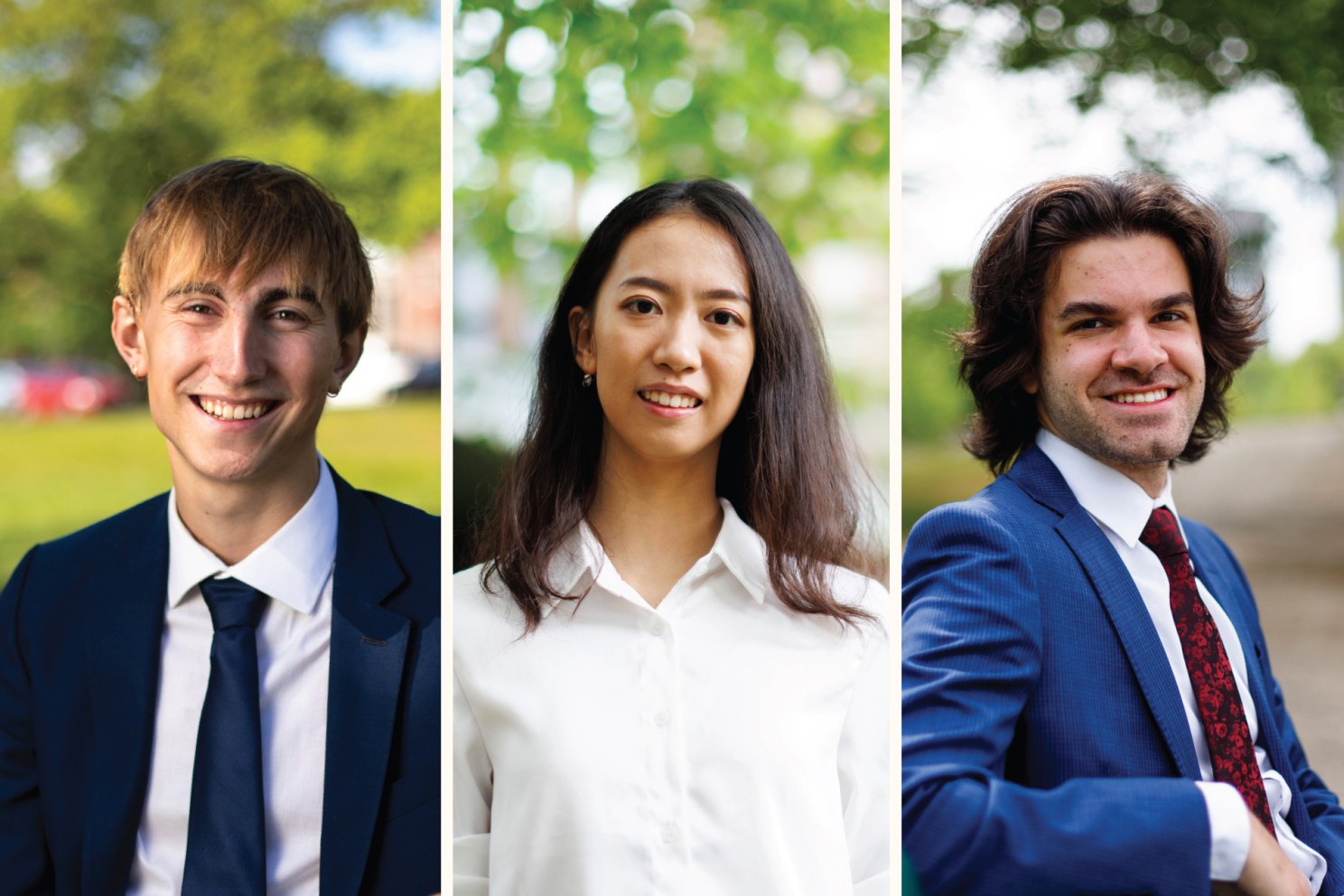

Graduates Thor Reimann (from left), Yurong “Luanna” Jiang, and Aidan Scully will deliver speeches Thursday at Commencement.

Photos by Veasey Conway and Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographers and Grace DuVal

Yurong ‘Luanna’ Jiang, Aidan Scully, Thor Reimann to deliver orations

Part of the Commencement 2025 series

A collection of features and profiles covering Harvard University’s 374th Commencement.

On Thursday, three graduating students selected in a University-wide competition will deliver speeches at Tercentenary Theatre — one of the oldest of Harvard’s Commencement traditions.

The student orators are Yurong “Luanna” Jiang, a graduating master’s student at the Harvard Kennedy School who will deliver the Graduate English Address; Aidan Scully, a graduating senior who will deliver the Latin Salutatory; and Thor Reimann, also a senior, who will deliver the Senior English.

‘Guard Our Humanity’

Yurong “Luanna” Jiang

Growing up in Qingdao, China, Jiang realized that education was a way to change the trajectory of her life. And it did.

High test scores earned her a full scholarship to a high school in Cardiff, Wales. She attended Duke University for her undergraduate education and will represent Harvard Kennedy School as the University’s Graduate Orator.

One of her friends had the same early understanding about education. But while Jiang had plenty of time to study, her friend — the daughter of fishmongers — had to help before and after school at her parents’ shop.

“It’s almost like you’re standing at a railway,” Jiang said, “and you know you have to hop off. Otherwise, your life will always be the same.” Jiang’s path shifted, and her friend’s didn’t.

The disparity got Jiang thinking about a question that would guide her educational journey: “What does it mean to have equality, fairness, and social justice?”

In Cardiff, where Jiang arrived not knowing English, she became interested in economics. “I trace it back to middle school,” she said. “When you see those hardships, why do they happen? What would the solution be?”

She continued studying economics at Duke and became increasingly interested in philosophy and politics, reading the work of thinkers such as John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, and William L. Rowe. To Jiang, economics felt like learning to drive a car, and philosophy felt like learning where to take it.

She also hosted a boxing club, having learned the sport growing up. Despite standing at around 5 feet, 3 inches tall, Jiang often prepared for competitions by sparring with men.

“It strengthens your character,” she said. “You have to look at them eye-to-eye and not be scared — because if you close your eyes, you cannot block the punch you can’t see, and you cannot hit a target you cannot see.”

Jiang worked in private-sector finance after Duke, thinking she might become an economist, but she felt the work was too far removed from the people she wanted to serve. The instinct brought her to the Kennedy School’s two-year M.P.A./I.D. program in international development.

She joined a class of 77 students from 34 countries. As she arrived, she writes in her address, “the countries I knew only as colorful shapes on a map turned into real people — with laughter, dreams, and the perseverance of surviving the long winter in Cambridge.”

She found her fellow students as idealistic as she was about supporting communities across the world — and one another on campus. When classmates lost loved ones or went through other tough experiences, friends from the program came to their aid, making sure they were eating and were not lonely.

“It makes us realize that this kind of empathy or human connection is beyond the countries,” she said.

She also continued studying philosophy, taking a class, and later a tutorial, with Arthur Isak Applbaum, Adams Professor of Political Leadership and Democratic Values. Reading philosopher Michel de Montaigne’s thoughts on recognizing the humanity of those very different from himself helped inspire her, more than 400 years later, to write her own reflection on the topic.

In her speech, Jiang encourages people to listen to one another without judgment, looking for shared beliefs rather than conflict.

“If we still believe in a shared future,” she writes, “let’s not forget: Those we label as enemies, they, too, are human. In seeing their humanity, we find our own.”

‘De Haereditatibus Peregrinis (On Foreign Inheritances)’

Aidan Scully

When your father is a high-school Latin teacher, “The Aeneid for Boys and Girls” is bedtime story material. At least, that was the case for Scully.

“The story was not in Latin,” he clarified, “but I had ancient history stories floating around from pretty early on.”

When it came time to choose a language at nearby Taunton High School, he remembers his father joking that he was allowed to study whichever one he wanted — as long as it was Latin.

Fortunately, Scully loved it.

“From day one,” he said, “I was hooked.” He took every Latin class the school offered, and when he was done, he continued independent study courses with his Latin teacher, Jessica Ouellette.

With her support, he worked toward publishing a translation of the first poem in Ovid’s “Amores,” from 16 B.C. Though others had translated the text before, he wanted to preserve its original metric playfulness.

“You can read Latin, and it can be an intellectual thing,” he said. “But I think trying to make poetry accessible to people in the way that it would have been 2,000 years ago bridges history in a way that is really exciting.”

Scully, a resident of Adams House, planned to concentrate in classics and government but realized his interests better aligned with a joint concentration in classics and religion. From sophomore year on, he split the bulk of his academic work studying the relationship between politics and religion in the ancient world and how they shape the modern U.S.

His former area of interest led to his thesis about how Romans in Late Antiquity balanced their Roman and Christian identities. While most people accept today that one can embrace both a religious and national identity, many Romans found this inconceivable.

“People at this time are trying to make sense of the fact of, ‘Well, if I am Roman and I am Christian, what does that mean? How are the two different? How do I make sense of the parts where it doesn’t seem like I can be both?’”

He found those fundamental questions relevant to the modern relationship between religion and government in the U.S. While mainstream U.S. history highlights religion’s impact on certain eras — The Great Awakening, the Civil Rights Movement — Scully studied its persistent presence over time.

Learning about evangelicalism and the landscape of Protestantism in the U.S. while studying ancient analogues fascinated Scully.

“This is the intersection I want to work at,” he said, “seeing what comparisons I can draw that maybe people haven’t thought to put in the conversation.”

His studies also affected how Scully approached his own faith and community service.

“Every work of religious scholarship begins with something like, ‘We don’t really know what religion is,’” Scully said, smiling. “It’s not easy to provide a definition that isn’t just a list of examples.” He finds that lack of certainty — and expansive approach — helpful in his volunteer work with queer interfaith communities.

“The lines we’re drawing are almost always arbitrary and usually based on at least one misconception,” he said. “Thinking critically about that leads to more inclusive activism.”

Besides introducing Scully to age-appropriate epics in childhood, Scully’s father, Christopher, also provided an example to Scully in a different way: He was Harvard’s Latin Orator in 1994. Family legend has it that his grandmother showed up not knowing that his father was about to deliver a Commencement address.

This time, though, Scully’s parents will know. He credits his mother, who graduated from Harvard as Elisa Leone in 1996 with a degree in social anthropology, for holding him accountable to reach the goals he set for education, and his life.

“I’ve been truly extremely fortunate to have a family that’s been so supportive of me doing a thing that’s kind of obscure and not, you know, employable,” he said. “The fact that things seem to be working out so far is a testament to them.”

‘This World is Not Conclusion’

Thor Reimann

Reimann was born and raised in Apple Valley, Minnesota, with parents who encouraged him and his two older siblings to pursue their own interests. It took each on a different path: His sister is a nurse; his brother is a nuclear submarine officer with the U.S. Navy; and Reimann hopes to attend law school and practice environmental law.

As a first-year, though, Reimann’s vision wasn’t quite so clear. In high school, he said, “I loved every subject.” He trusted that he’d find his way to a fulfilling academic experience and, as one of the only openly queer students from his high school, “the personal space to fully explore who I was,” he writes in his English Oration.

At first, Reimann, a resident of Mather House, thought he might concentrate in history and literature or social studies, which would allow him to take a broad range of classes. A general education course he took freshman year shifted his trajectory: “Life and Death in the Anthropocene.”

The course, taught by Naomi Oreskes, Henry Charles Lea Professor of the History of Science, encouraged Reimann to think about climate change and environmental problems from a range of academic and personal perspectives.

“They really touch every aspect of human life that’s out there,” he said. “I found myself constantly thinking about it when I would leave class.”

A lover of nature who would go on to join the steering committee for the First-Year Outdoors Program, Reimann decided to pursue a joint concentration in environmental science and public policy and comparative religion. Though he appreciated the technocratic element of environmental studies, the added focus on religion helped him balance policy with a big-picture idea of what he was trying to protect in the first place.

With guidance from Terry Tempest Williams, the Harvard Divinity School writer-in-residence, Reimann developed a deep interest in conservation. His joint major, and his conservation interest, sparked his senior thesis on Bears Ears National Monument, a federally protected area in southeastern Utah.

One of the most culturally dense landscapes in the U.S., the federal monument contains artifacts from different Native American tribes dating back thousands of years. Reimann was interested in how political organizing across different tribes that described the area as “sacred” helped earn it federal protection in 2016 — and how the same idea of “sacredness” was used by different groups to reduce its size the following year.

“The government just doesn’t have the right policy tools to be able to create space to talk about these claims,” he said.

Just as his thesis can be traced to first-year discoveries, so too can his speech. The title, “This World is Not Conclusion,” is borrowed from an Emily Dickinson poem that he read during a first-year seminar.

“I was having this big moment of, ‘Oh gosh, what am I going to do? How do I think about this opportunity?’” said Reimann. “And I think a lot of the poem is about how the circumstances of the day that you’re in right now are going to change. There’s going to be something that comes next.”

He felt especially struck by the final two lines of the poem: “Narcotics cannot still the Tooth / That nibbles at the soul —”

“You can have a lot of money or you can have a lot of power,” Reimann said, “but still, the tooth is going to nibble — so you better listen.”

The poem helped him be comfortable letting his curiosities guide him as he started his undergraduate experience. It also helped him process its conclusion.

“In this time when there’s a lot of uncertainty and fear, I think it can be reassuring that there is something coming next, and we have the agency to go and be a part of creating that,” he said. “It’s not just an end. New things are beginning.”