Can Trump fire Fed chairman?

U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell at a news conference following a Federal Open Market Committee meeting in March.

Photo by Sha Hanting/China News Service/VCG via AP

Law professor and former Fed Board member says it’s possible but likely market reaction should give pause

President Trump has had a difficult relationship with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

Concerns over Trump’s global tariff plans roiled markets earlier this month. Powell, who was first nominated to the post by Trump in 2017, noted the president’s policies could lead to higher inflation and slower growth.

Trump accused the Fed chair of failing to boost the economy by not being more aggressive about cutting interest rates. (The two also disagreed over rates in Trump’s first term.) He also hinted he was contemplating ousting Powell before his four-year-term expires next year, further unsettling markets.

Many analysts said such a move would gravely harm the Fed’s longstanding independence and is, according to Powell, “not permitted under the law.”Trump later said he had no plans to fire Powell.

In this edited conversation, Daniel Tarullo, Nomura Professor of International Financial Regulatory Practice at Harvard Law School, discusses the potential fallout should the president make good on his threats to fire Powell. Tarullo served on the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the body that decides on interest rates, from 2009 to 2017.

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 allows governors to be removed for cause, but it doesn’t say anything about the FOMC chair. In your view, does a president, as head of the executive branch, have the power to oust Powell?

There are two separate issues. One is a statutory interpretation issue — whether the addition of the amendment to the Federal Reserve Act in the 1970s, which provided for Senate confirmation of the chair for a four-year term, incorporates the “for cause” protection the original Federal Reserve Act afforded to all members of the Board of Governors.

The alternate reading would be that the four-year term for the chair as chair is not protected by the “for cause” provision.

The second issue, of course, is whether — regardless of what the Federal Reserve Act provides — the Supreme Court believes that the Constitution gives the president removal power for anybody at an independent agency who is performing what the court considers to be “executive” functions. Those two issues are related, but in the first instance, they’re actually distinct.

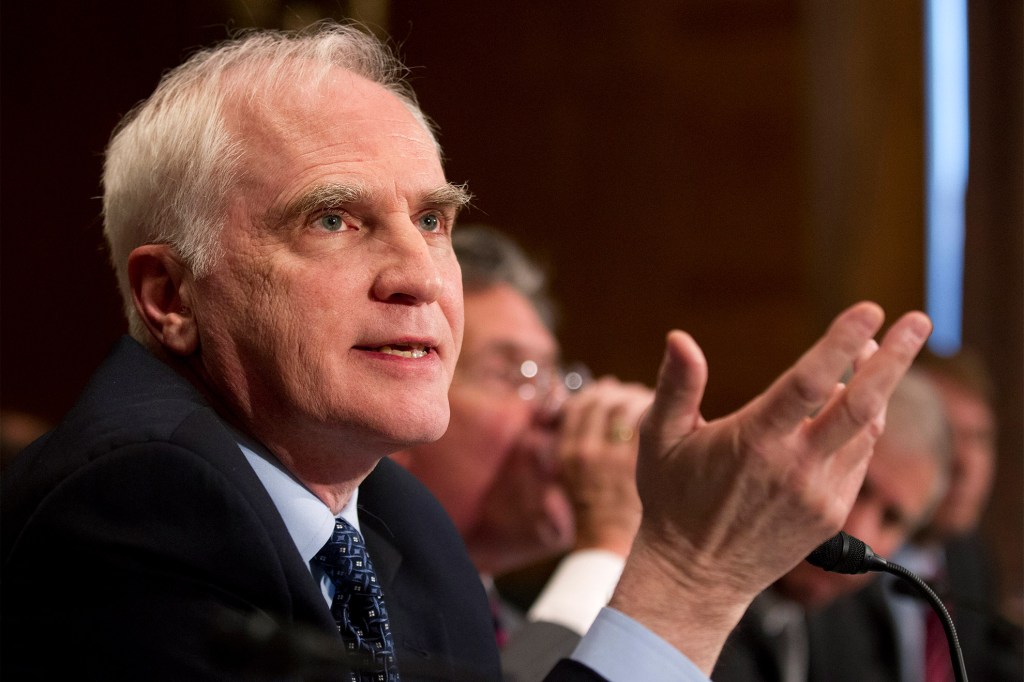

Daniel Tarullo.

Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP file photo

Is the Supreme Court likely to support such a move given recent decisions on the scope of executive authority?

I think most observers expect some further erosion of the famous 1935 decision Humphrey’s Executor, which for 85 years was understood as validating “for cause” protection for the principals at independent agencies.

Whether the court will further erode Humphrey’s step by step or will sweep it away in a single case remains to be seen.

The issue, though, would be whether the Fed (and perhaps other agencies) would be treated differently. And I think we’ve seen some hints from three of the conservative justices — Samuel Alito, John Roberts, and Brett Kavanaugh — that they may regard the Federal Reserve differently from other agencies.

They may still hold a broad view of the president’s authority, but favor a carve-out for the Fed?

Yes. None of the three justices has done more than hint at a potential difference, so we don’t have a sense of what their basis for distinction would be.

One that is available is the legacy of the Federal Reserve in the First and Second Banks of the United States. There could be an argument that from the very first Congress, which convened right after the Constitution was ratified, there was an acknowledgement that Congress could create an independent central bank.

Now, the First Bank of the United States was not a central bank as we would think of it today, but in the late 18th century it was pretty close to what was then thought of as a central bank, epitomized by the Bank of England. So that argument would be available. It’s not overwhelmingly compelling, but it’s arguable. Besides, I haven’t thought that the court’s recent decisions on the “for cause” removal protection have themselves been compelling, so there is an opportunity for the court to do some picking and choosing.

Is there a good legal argument for removing Powell before his term ends?

We can go back to the fact that for 85 years “for cause” protection in independent agencies was generally thought to be the prevailing doctrine.

But the Supreme Court gave substantial reason to question that proposition in Seila Law, the 2020 case that found Congress’ grant of “for cause” removal protection to the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to be unconstitutional.

So, it’s the court which has changed that 85-year-old understanding and left unanswered the question of how broadly it will ultimately rewrite Humphrey’s Executor.

If there were an effort by the president to remove the chair, the market reaction would be very significant — well before any court had an opportunity to pass on the issue. The anticipated market effect is a disincentive to try to remove the chair, no matter how unhappy the administration may be with his policies.

Given Powell’s term as chair now has only a year to run, that’s probably an additional argument for just waiting until the president can name his own person as a successor. And so, at some level, the market is as much a protection for the Board of Governors as the law may end up being.

Why is Wall Street rattled by the prospect of Powell removal?

Sitting administrations will almost always favor a looser monetary policy in order to promote near-term economic growth. The point of having some independence for a central bank is that the central bankers can look at the potential impact on inflation over the medium term and try to keep inflation closer to what today for the Fed is a 2 percent target. It’s a pretty simple rationale, but it’s a powerful one.

What markets fear is that if a president removes the chair or other members of the Board of Governors, it would be with the intent of having a looser monetary policy. At that point, the markets’ trust in the central bank will be substantially undermined, and thus, the central bank’s credibility as an inflation fighter will be undermined. Longer-term interest rates will then rise, probably dramatically.

Thus, there’s the potential for an odd situation in which the Fed central bank is more responsive to the administration’s desire for near-term growth and reduces short-term rates, but markets, thinking that’s going to be inflationary, essentially demand a higher premium for holding longer-term Treasuries and other longer-term debt. It’s for that reason that I believe that any action by any administration to try to remove the chair or other members of the board is ultimately self-defeating.

Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent has quite understandably been focused on the 10-year Treasury rate, because that rate is very important for investment decisions throughout the economy. One would presume the administration doesn’t want to drive up that rate because of uncertainty in markets.

How much power does the chair actually have over internal policy deliberations?

There’s still some significant public misperception on just how powerful the chair is within the board and within the FOMC.

For a period when Alan Greenspan was chair, his preferences and decisions apparently more or less drove FOMC decisions. By the time I joined the Board of Governors in early 2009, that was certainly not the case. I think Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, and now Jay Powell have all had to do a substantial amount of internal consultation and internal work trying to forge a consensus around monetary policy.

There’s no question that the chair is far and away the most important individual on the FOMC. But it’s not the case that the chair can simply dictate what policy is going to be and the rest of the FOMC will fall into line.

If Powell was replaced by someone with a certain pedigree, would that calm market jitters?

I think if there were an effort to remove him, the identity of the successor wouldn’t be all that consequential because I believe markets would read into the very act of removal an intent to have a significantly more accommodative monetary policy.

If Jay Powell is allowed to serve out his four-year term, then obviously the identity of the individual whom the president nominates to succeed him will be of substantial interest to markets.