Letting the portraits speak for themselves

Artist Robert Shetterly ’69 and Brenda Tindal, chief campus curator.

Photos by Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

New exhibit elevates overlooked voices as it explores hope, change, and how we see others

In 2002, two Harvard affiliates, artist Robert Shetterly ’69 and the late Harvard Medical School Professor of Neurology S. Allen Counter, launched portraiture projects driven by a desire for change. Shetterly, disillusioned by the U.S. government’s decision to go to war in Iraq, had turned to painting people who inspired him as a form of protest and solace. Meanwhile, Counter, the founding director of the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations, wanted to address issues of representation by diversifying the portraits displayed across Harvard’s campus.

What emerged were Shetterly’s “Americans Who Tell the Truth” series and the Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project, both of which use portraiture as a form of storytelling to amplify overlooked voices.

“Every one of the people I paint has a particular kind of courage that meets a particular moment,” Shetterly told chief campus curator Brenda Tindal in front of an audience at Cabot House. “They take the risk, often, of being either ostracized by society or legally entangled, something that’s going to put them in some oppositional relationship with large segments of this country. I am so drawn to that. It’s because of that courage that we have social justice.”

“Every one of the people I paint has a particular kind of courage that meets a particular moment”

Robert Shetterly

Last week, the Office for the Arts, the Harvard Foundation, and the Harvard College Women’s Center staged an exhibition at Cabot that highlighted portraits of Harvard affiliates from both projects. Titled “Seeing Each Other: A Conversation Between the Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project and Americans Who Tell the Truth,” it included paintings from Shetterly and the Portraiture Project’s Stephen Coit ’71.

In honor of Women’s Week, the portraits spotlighted female changemakers, including former U.S. Treasurer Rosa Rios ’87, musicologist Eileen Southern, civil rights activist Pauli Murray, ethnomusicologist Rulan Pian, youth development advocate Regina Jackson, and former Maine State Sen. Chloe Maxmin ’15. Portraits of Counter and W.E.B. Du Bois, the first Black Ph.D. to graduate from Harvard, are also included.

“History reminds us that the fight for gender equity has often been strengthened by allies who have used their platforms to challenge injustice and uplift the voices of those most marginalized,” said Habiba Braimah, senior director of the foundation, introducing the conversation between Tindal and Shetterly. “By showcasing their portraits alongside the extraordinary women we honor tonight, we acknowledge that meaningful progress is achieved through both advocacy and solidarity, reinforcing the idea that the pursuit of gender equity has always been and must remain a shared responsibility.”

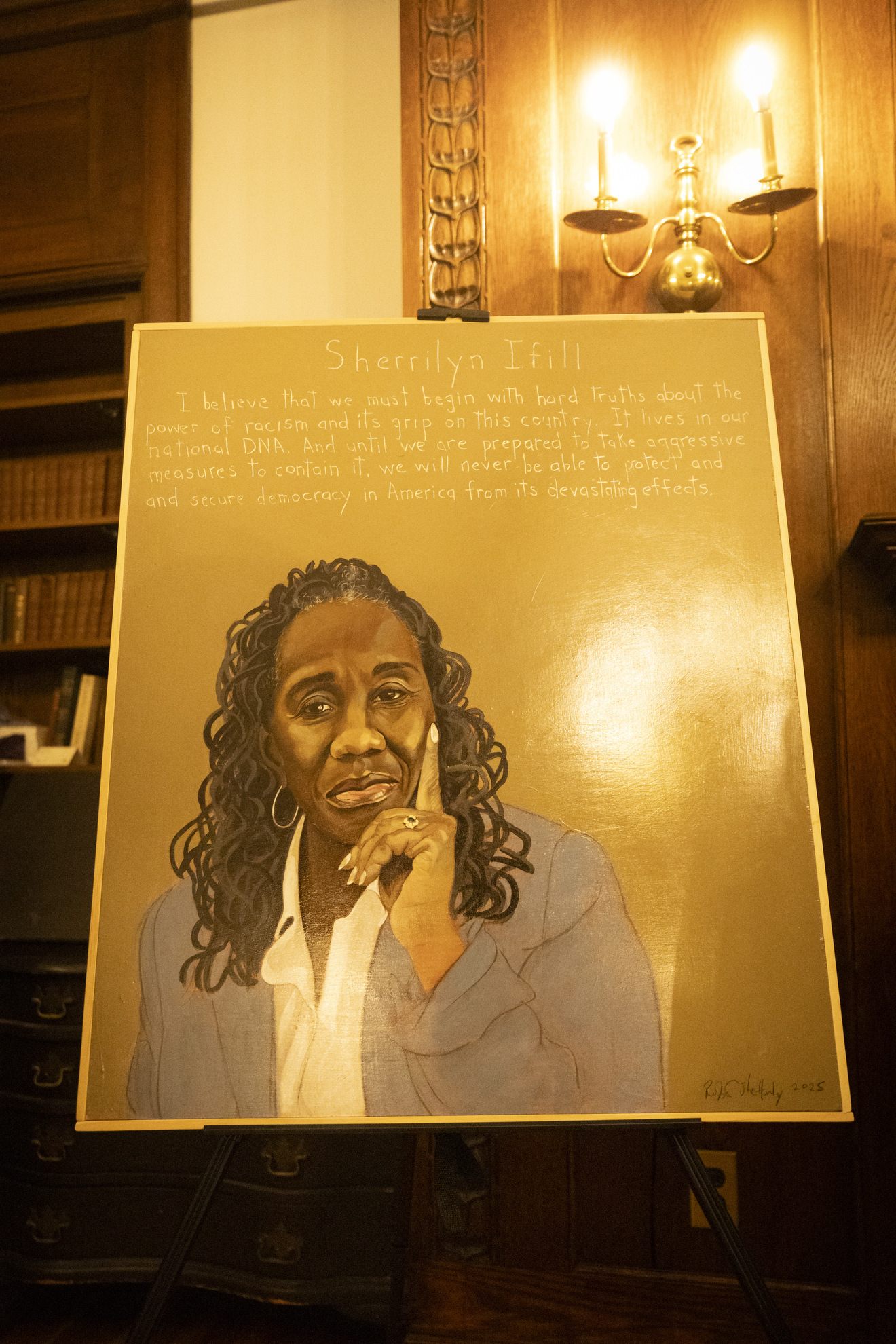

At the exhibition opening, Shetterly also unveiled a new portrait of civil rights lawyer Sherrilyn Ifill, former president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, who was Steven and Maureen Klinsky Visiting Professor of Practice for Leadership and Progress at Harvard Law School from 2023 to 2024. In the portrait, Ifill, wearing a blue suit jacket, gazes outward with a thoughtful expression, chin resting on one hand.

Having attended Iffil’s 2024 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Commemorative Lecture at Harvard, Adaolisa Agbakwu ’28 remembered being moved by the lawyer’s analogy of the Civil Rights Movement as a cycle of planting and harvest — laying groundwork so future generations can reap the benefits.

“The portrait’s warm and the cool undertones spoke to me of this almost solace within her but also this fiery passion and energy that she has toward her work and dedication to the cause that she exhibits in everything she does,” Agbakwu said.

In his discussion with Tindal, Shetterly said that what began as a plan to create 50 portraits for his series has since grown into a collection of more than 200. Shetterly took his first art course at Harvard — a drawing class in the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

“What I noticed was that when I had to look at something — my own hand, an apple, a pencil, an old shoe, a glove — in order to draw it, I had to really see it for the first time,” Shetterly recalled. “That changed my life.”

Shetterly paints on wood panels with brushes, palette knives, and his fingers, and uses a dental pick to carve a quote from his subject into the wood above their likeness. The use of quotes was partly inspired, he said, by hearing that most gallery attendees only spend seven seconds in front of a painting and wanting to encourage viewers to slow down and look.

“Having the words incised into the surface gives them a slightly different weight than if they have been painted on the surface,” Shetterly said. Once in the painting, they seem to be a little bit stronger, more organic, as though they really come from the person in the painting.

Coit, who has contributed more than two dozen portraits to the Harvard Foundation Portraiture Project, told the audience that he feels his role is to showcase what his subjects want to reveal about themselves.

“When I was painting somebody I would say, ‘What do you want to say in your portrait?’” Coit said. “We’d think about the background, we’d think about what they were wearing, we’d think about the expression on the face, and they would create it with me. I always felt my job was a little bit to create a kind of immortality, so it felt like they were in the room with you, delivering that message.”