Every picture tells a story

Photographer Susan Meiselas (left) speaks with attendees following the talk.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Photographer Susan Meiselas shares how ‘44 Irving Street Cambridge, MA’ shaped her career

Susan Meiselas didn’t set out to be a photographer. The documentary photographer, filmmaker, and president of the Magnum Foundation was working toward her master’s degree at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 1971 when she shot her groundbreaking “44 Irving Street, Cambridge, MA series,” which is now on view at the Harvard Art Museums.

Best known for her documentary photography of the late 1970s insurrection in Nicaragua and her photos of carnival strippers later that decade, Meiselas looked back on the Irving Street black-and-white prints during a recent gallery talk and shared how they helped shape the career that followed.

Initially, she said, she was focused on her degree when a course in photography “with a sociological bent” caught her eye. (She no longer remembers the name of the course.) For a class project, she chose to shoot the other inhabitants of her Cambridge boarding house.

“The camera was this way to connect,” she said. “I knew no one, and I began to knock on doors.”

Going around to the different apartments, she realized that each space in the old building “had a different character.” Seeing how the residents personalized their rooms, “I became fascinated by what they did with their space.”

Visitors gather to examine the photographs Meiselas discussed.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographersity

Even more captivating than the personal use of space, Meiselas found, were the interactions with her neighbors, whom she identified only by their first names. To start with, she would explain that she was a student, learning photography. “I’d ask them if there was a place in their room that they would sit for a portrait.” The results vary, with subjects settled into easy chairs or lounging on the floor, some in clean, well-lit areas and others surrounded by books and papers. Once she developed the photos, she’d return with a contact sheet to show her subjects. “That was the moment where something else for me happened,” she said. After her subjects had viewed the photos, she would ask them, “How do you feel about yourself?”

Those written responses, which can be read by accessing a QR code on the exhibit wall, make the installation complete, said Meiselas, who submitted the letters along with the photographs for class. “They wrote me either about how they felt about themselves, how the picture did or didn’t portray them.”

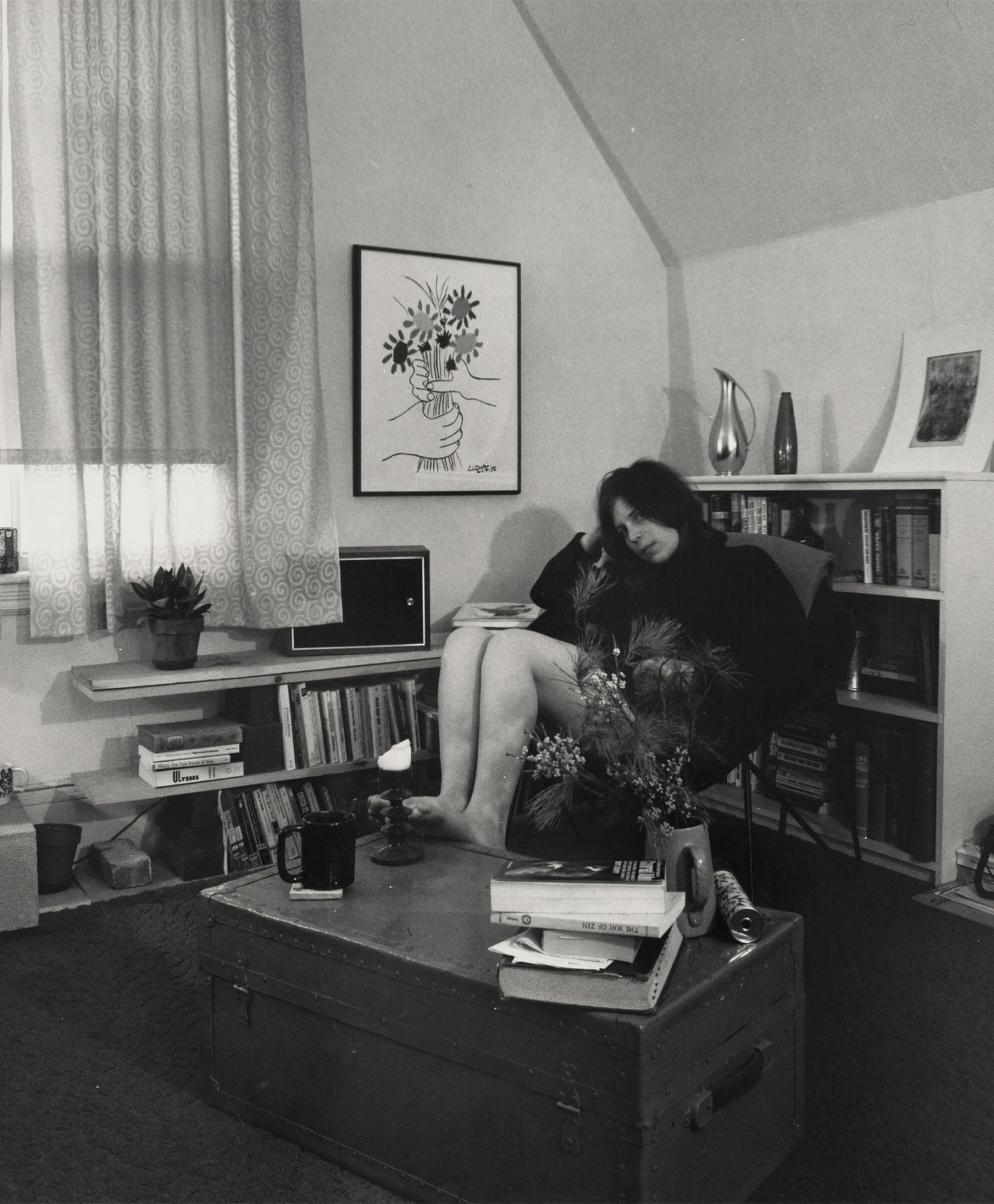

“Gordon, 44 Irving Street, Cambridge, MA,” 1971, gelatin silver print.

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum; photo courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

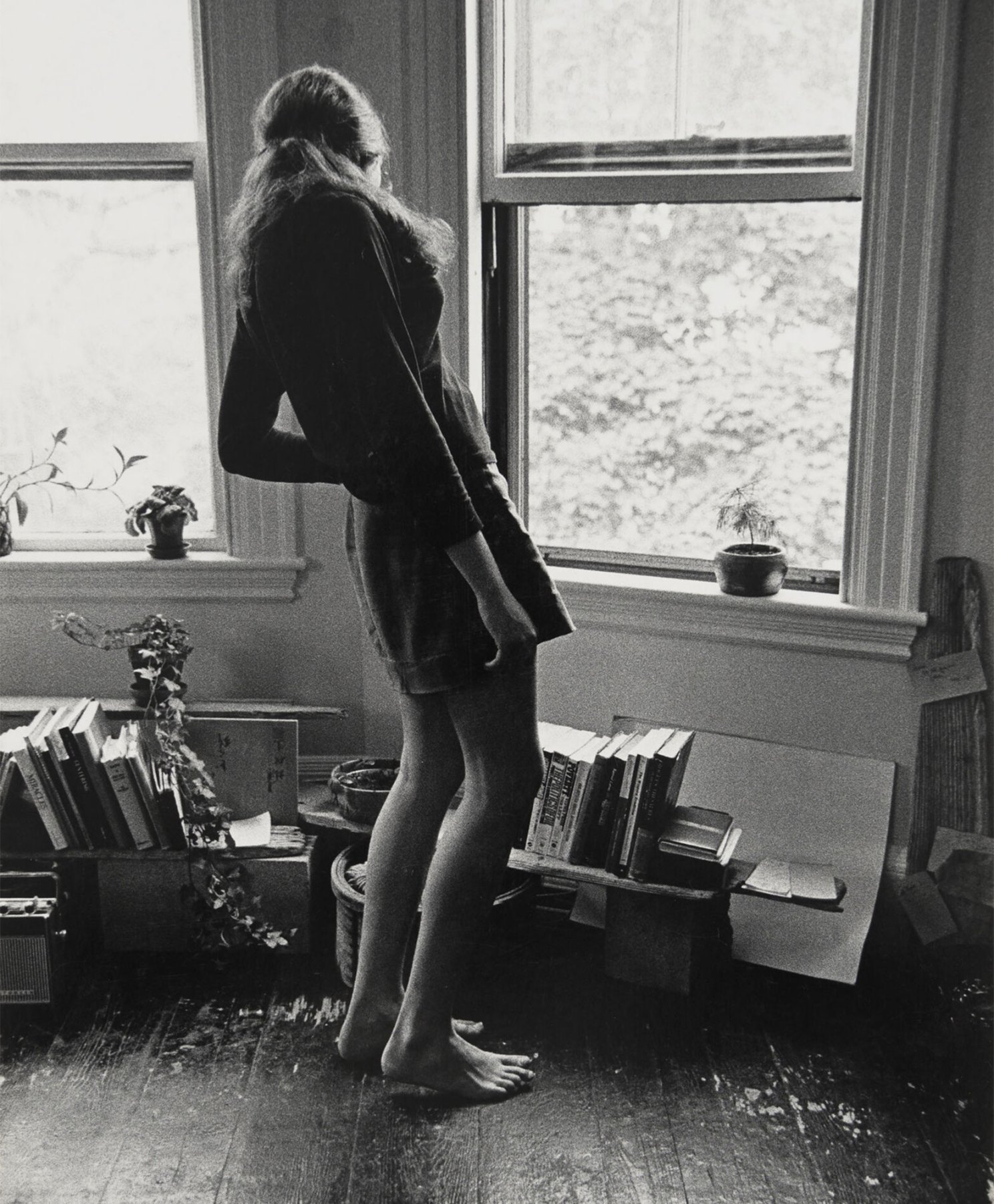

“Carol, 44 Irving Street, Cambridge, MA,” 1971, gelatin silver print.

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum; photo courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

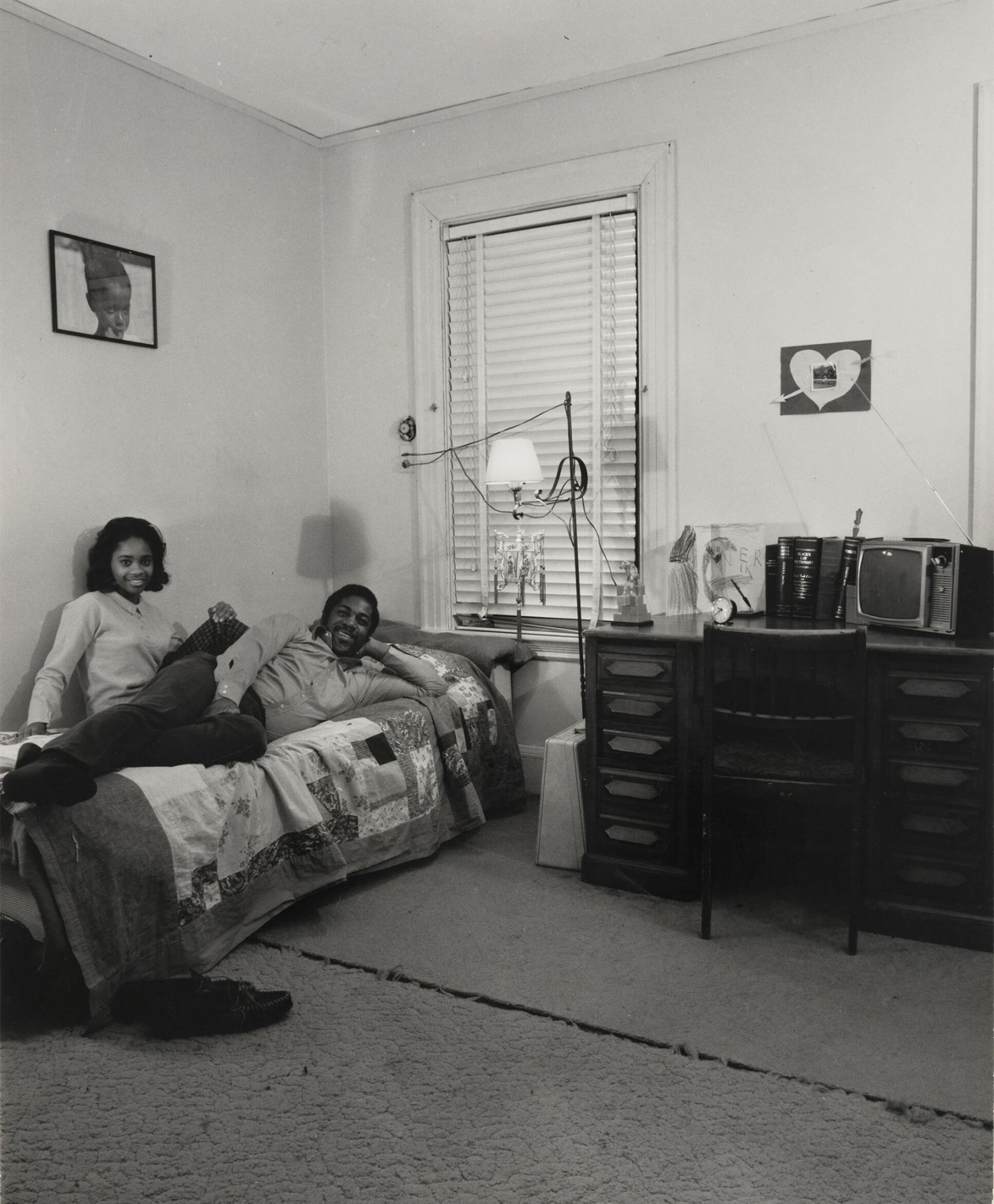

“Mike and Alease, 44 Irving Street, Cambridge, MA,” 1971, gelatin silver print.

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum; photo courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

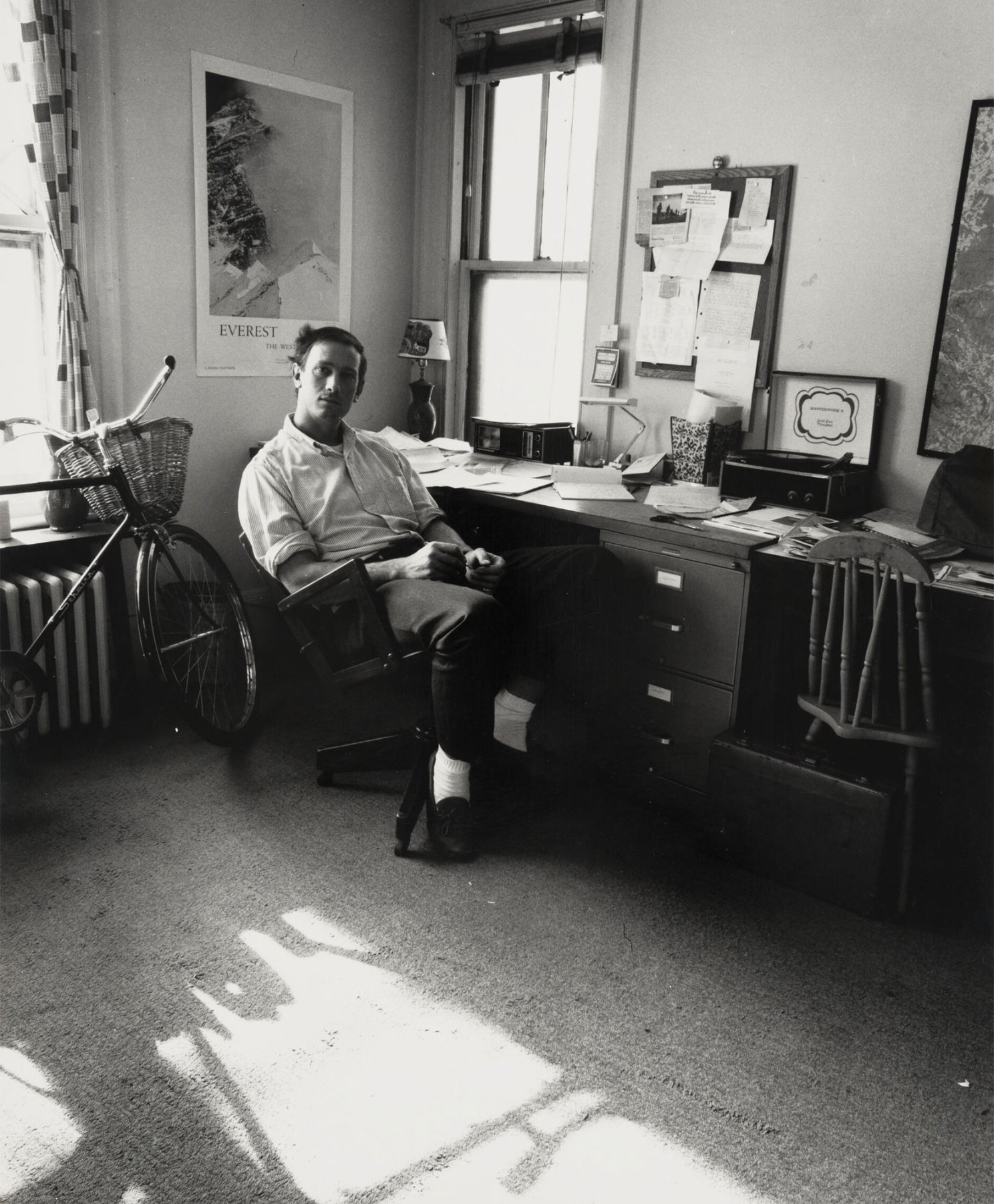

“Cromwell, 44 Irving Street, Cambridge, MA,” 1971, gelatin silver print.

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum; photo courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

“Susan, 44 Irving Street, Cambridge, MA,” 1971, gelatin silver print.

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum; photo courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

At the gallery talk, she read excerpts of those responses aloud. Her former neighbor Gordon, for example, is shown slumped in a chair, with books and a television behind him. “I wouldn’t have chosen to live alone. I was forced to,” he wrote, perhaps to explain his dejected posture. “That’s the way I am, somewhat distant. I get turned in on myself. I look at this place as a way station.”

In other samples of the QR-accessible text, another neighbor, Carol, responded to her photo, which shows her surrounded by her books. “I like to think my face conveys the way I feel during my most creative jam sessions: slightly dissatisfied at my slowness, slightly chagrined by the progress and quality so far lacking.” Another, Barbara, focused on herself: “My picture shows me … in my small world,” she wrote of the photo, which shows her typing at a desk, “looking out at everyone and everything.”

Those letters became Meiselas’s focus. “I didn’t leave class thinking ‘I’m going to be a photographer,’” she said. Instead, “I became fascinated by the camera as a point of connection.”

What interested her, she continued, was how the subjects responded. The experience also raised two themes that have become constants in her work: “the pleasure of the connection, and the problematic nature of the power of representation.”

Meiselas explored these themes recently in the book “Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography,” which she calls “an attempt to really look at photography as including others.” (The book was co-authored with UC Berkeley Professor of African American Studies Leigh Raiford; Yale University Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Laura Wexler; photographer Wendy Ewald; and Brown University Professor of Modern Culture and Media Ariella Aïsha Azoulay.) Such an examination is necessary, she said, because the relationship between the subject and the photographer can be fraught, balanced between “what’s positive and collaborative and inclusive and participatory, and what is more problematic.”

After the “Irving Street” project, Meiselas went on to get her education degree and teach. Working with elementary school students at an experimental school in the South Bronx, she again incorporated photography into her work. Using simple pinhole cameras, her students took photos of their surroundings and their neighbors “and made little books,” she recalled.

“They used images to tell stories. It wasn’t about the formalism of photography,” she said. “It was about the narrative and the connectivity. It was: Take your pinhole camera, go out on the street, meet the butcher…” Through these photos, Meiselas said she hoped to give her students “a notion of photography as an exchange in the world.”

Through all these projects, she sees the thread of relationship-building. Looking back once more on the “Irving Street” series, she noted: “This project has always resonated as the beginning of my practice.”

Photographs from Susan Meiselas’ “44 Irving Street, Cambridge, MA” portfolio are on display at the Harvard Art Museums through April 6.