An architect-detective’s medieval mystery

Photos by Justin Knight; photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

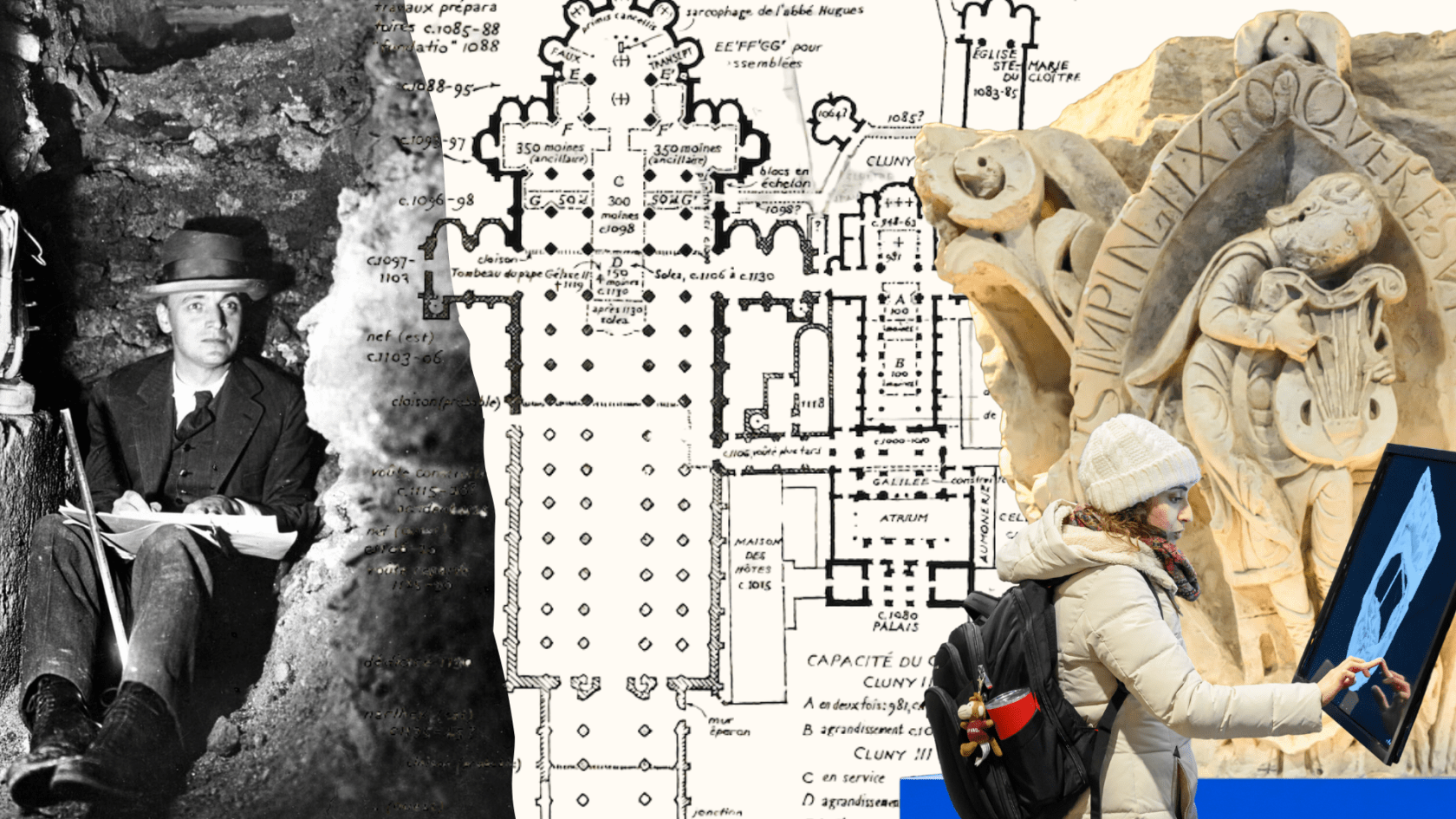

Exhibit traces scholar’s quest to reconstruct abbey destroyed after French Revolution

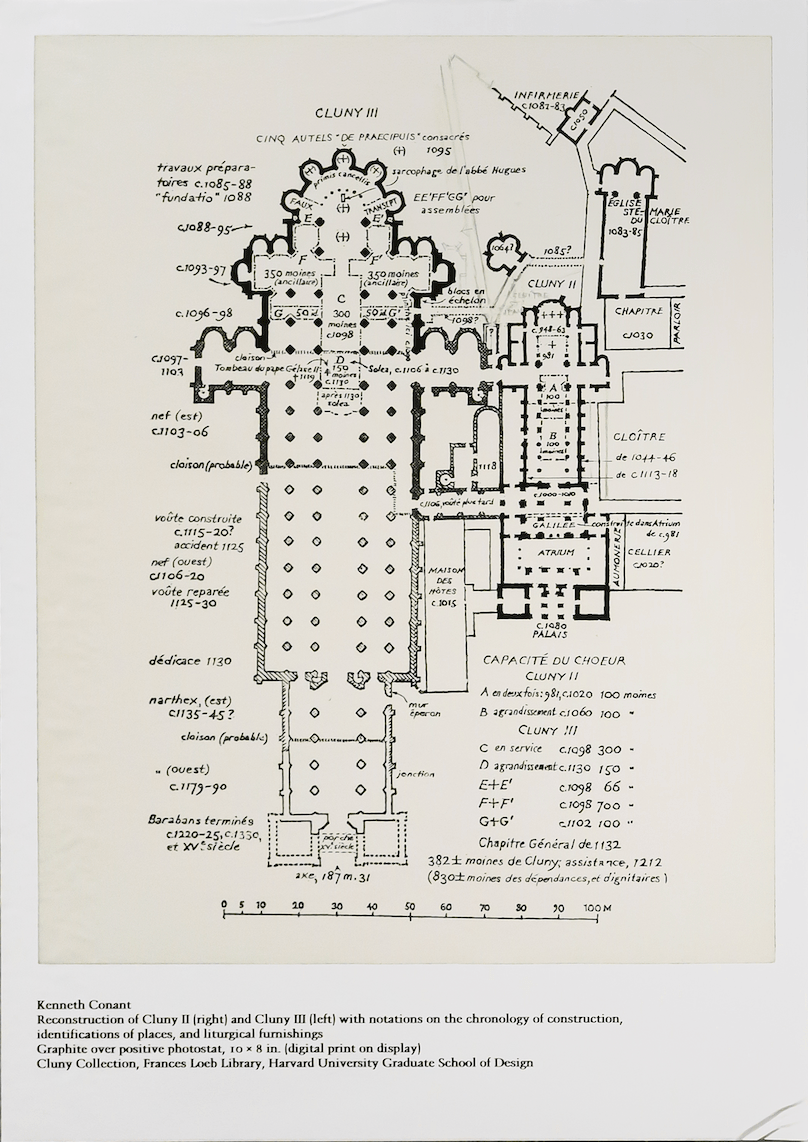

Cluny III, once the largest building in Europe, was little more than rubble when Harvard architectural historian Kenneth Conant laid eyes on it in the 1920s. His efforts to painstakingly recreate the medieval abbey as it looked in the Middle Ages — outlined as part of an exhibition now on view at the Graduate School of Design — illustrate how architects learn to see what isn’t there.

“Envisioning Cluny: Kenneth Conant and Representations of Medieval Architecture, 1872–2025,” on view in the Druker Design Gallery through April 4, explores the ways that the study of medieval architecture has changed, from hand-drawn sketches to photography to 3D digital models and virtual reality.

“The exhibit is the story of a man and his passion, which is the Cluny abbey church, and how we can experience it today using modern tools,” said Matt Cook, digital scholarship program manager at Harvard Library, who worked closely with curator and architectural historian Christine Smith. “Several teams across Harvard Library allowed Christine to realize her vision for the exhibit with emerging technology.”

The eight plaster casts of Cluny III capitals, on display at the Druker Design Gallery, have been an enduring mystery for scholars.

Construction began on the Benedictine abbey of Cluny III, located in the Burgundy region of France, in 1088. It stood for more than 700 years, growing to more than 500 feet long and 100 feet high; at one time, it was home to about 1,000 monks. But after the French Revolution, the impressive structure was demolished and sold for scrap materials.

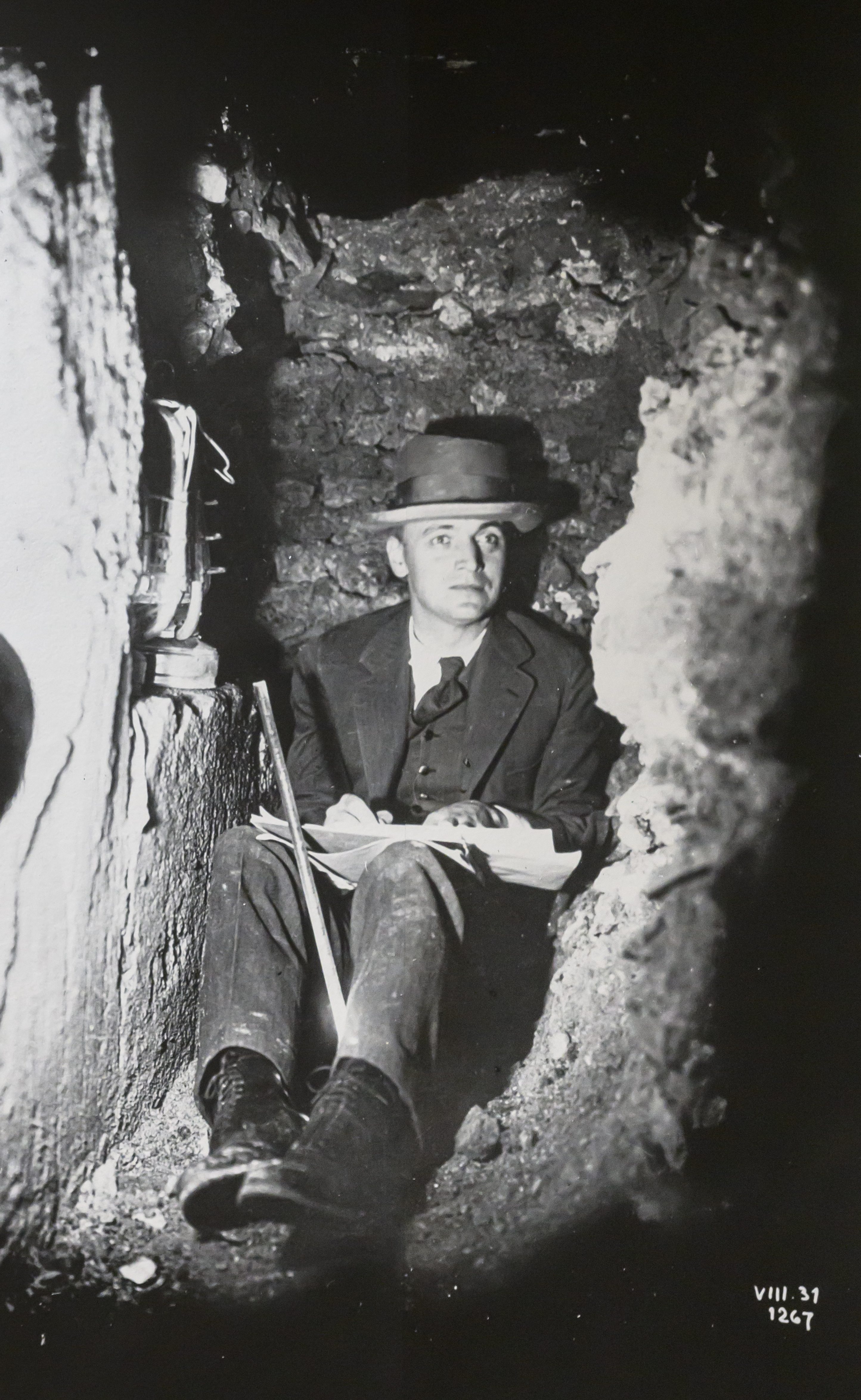

When Conant first arrived at Cluny decades after its destruction, all that remained was the south transept and eight partially destroyed capitals, or the decorative tops of columns, which once stood behind the altar.

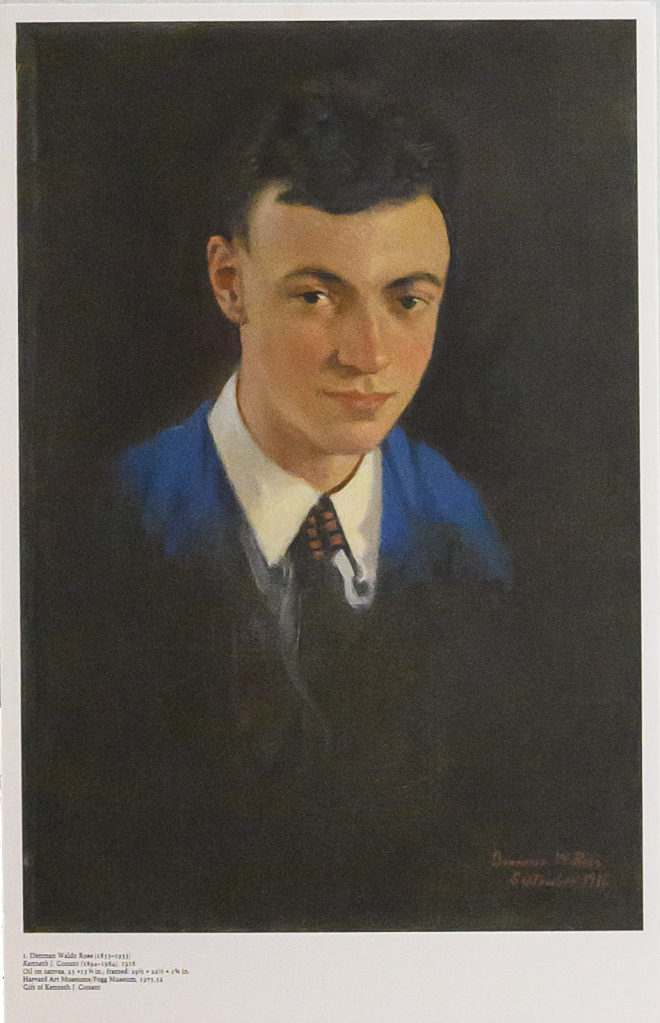

Conant received his undergraduate and graduate degrees from Harvard and taught architectural history at the University from 1920 to 1954. It was an era when architectural historians were still learning to classify medieval architecture and to understand what a building might have looked like in its original form before pieces were added or taken away over the centuries.

“It’s a kind of an idealism,” said Smith, who is the Robert C. and Marian K. Weinberg Professor of Architectural History.

The “idealist” task that Conant gave himself was to imagine Cluny III as it once was, in excruciating detail, based on what he knew of similar buildings and on 20 years of excavations.

Conant tried to identify the original form of the abbey church before later additions were built.

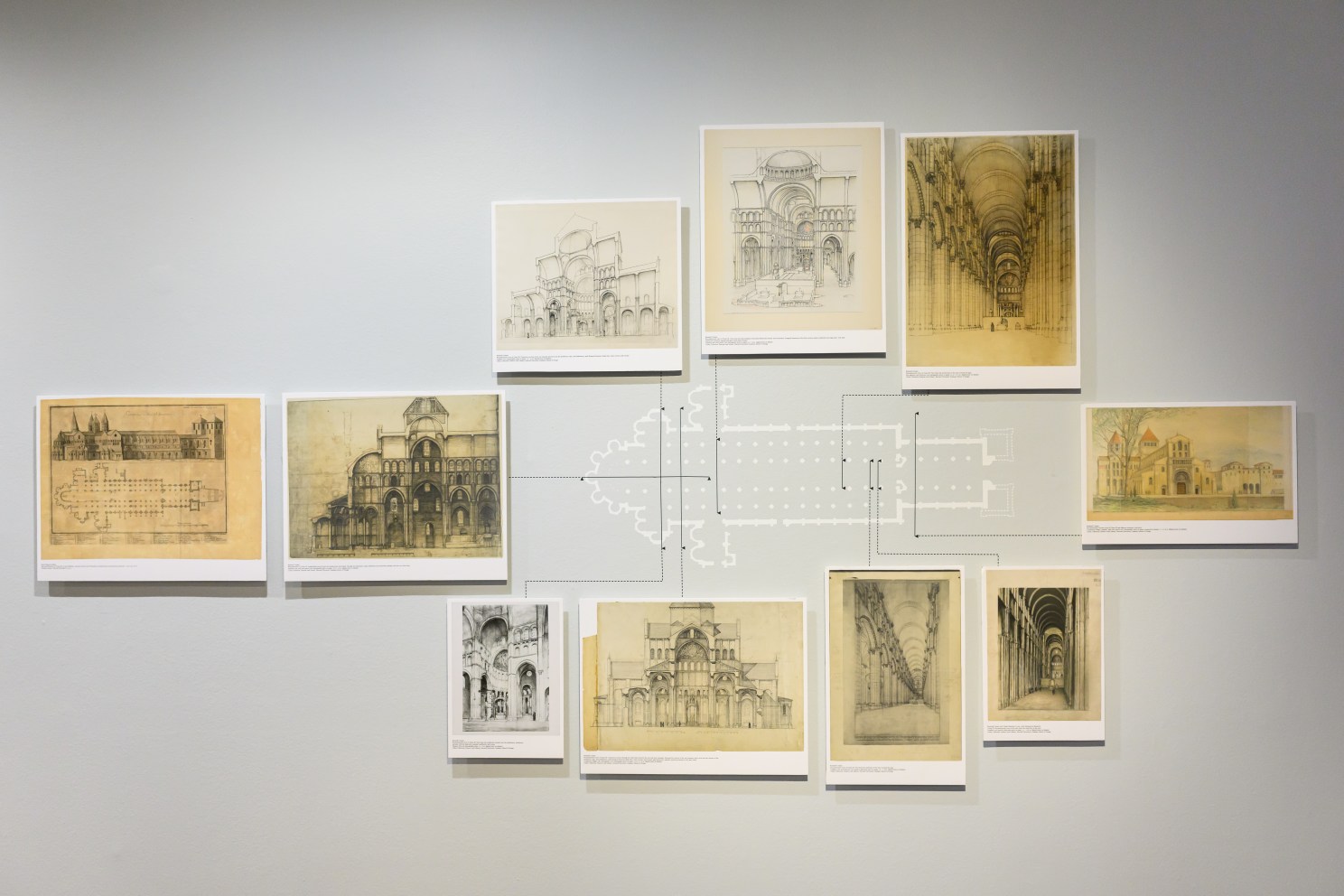

Conant made precise illustrations of the inside of Cluny III from a variety of perspectives, all without ever seeing the building.

“It was unimaginably immense,” Christine Smith said of Cluny III.

Like Conant himself, “Envisioning Cluny” attempts to recreate the feeling of being inside one of medieval Europe’s largest buildings, long since ruined.

“In my own work, when I’m studying something, I try to know it in such reality and detail that I live it,” Smith said. “I think that’s what he’s doing: He’s living it. He wants to see it. He wants to feel it in many different ways. He wants to understand it objectively, but also in terms of the color, the light, how you moved around in it, how it felt to be there.”

Technology allows viewers to interact with architectural designs in ways Conant’s contemporaries could not have imagined.

The enduring mystery of the Cluny capitals

The eight capitals discovered at Cluny III fascinated Conant. They were damaged, with key details missing, but each seemed to feature ornate designs of people, plants, and musical instruments. It wasn’t clear which sides ought to face the front, or what order they should go in, or if they even told a cohesive story.

“Some people think they’re all by one sculptor; other people think they’re by two identifiable sculptors; other people think we don’t know,” Smith said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty about them, which is what’s fun.”

Early in his career, Conant hoped the columns told a single story about the virtues of monastic life, Smith said. But eventually, he came to believe there was little uniting them as an octet. To this day, there are no firm answers, but they remain an object of study as one of the earliest examples of figural sculpture in the Romanesque era.

From plaster casts to 3D

Contemporary students of architectural history don’t have to rely on the stone capitals themselves, or even the unwieldy plaster casts that scholars have traditionally used as aids.

Using a method called photogrammetry, Harvard Library Imaging Services photographed the plaster casts of the Cluny columns to create the 3D models that are featured in the exhibit. The team took hundreds of individual photos of each capital cast to create each model. Additionally, library conservators, archivists, and curators prepared the print and photo reproductions on display.

With the 3D scans, Smith and her students can zoom in, rotate, and rearrange the eight capitals and each of their designs in a way previous generations never could, giving them new insight into the enduring puzzle of the octet.

“I can compare them in a way that I can’t with the plaster cast,” Smith said. “I can look at all eight of them in a row.”

It’s a different experience for today’s architectural students than for Conant and his contemporaries, she said. But at the core, the exercise is the same: Learning to see what’s there, and learning to imagine what’s not.

“Envisioning Cluny: Kenneth Conant and Representations of Medieval Architecture, 1872–2025” is on display through April 4 in the Druker Design Gallery.