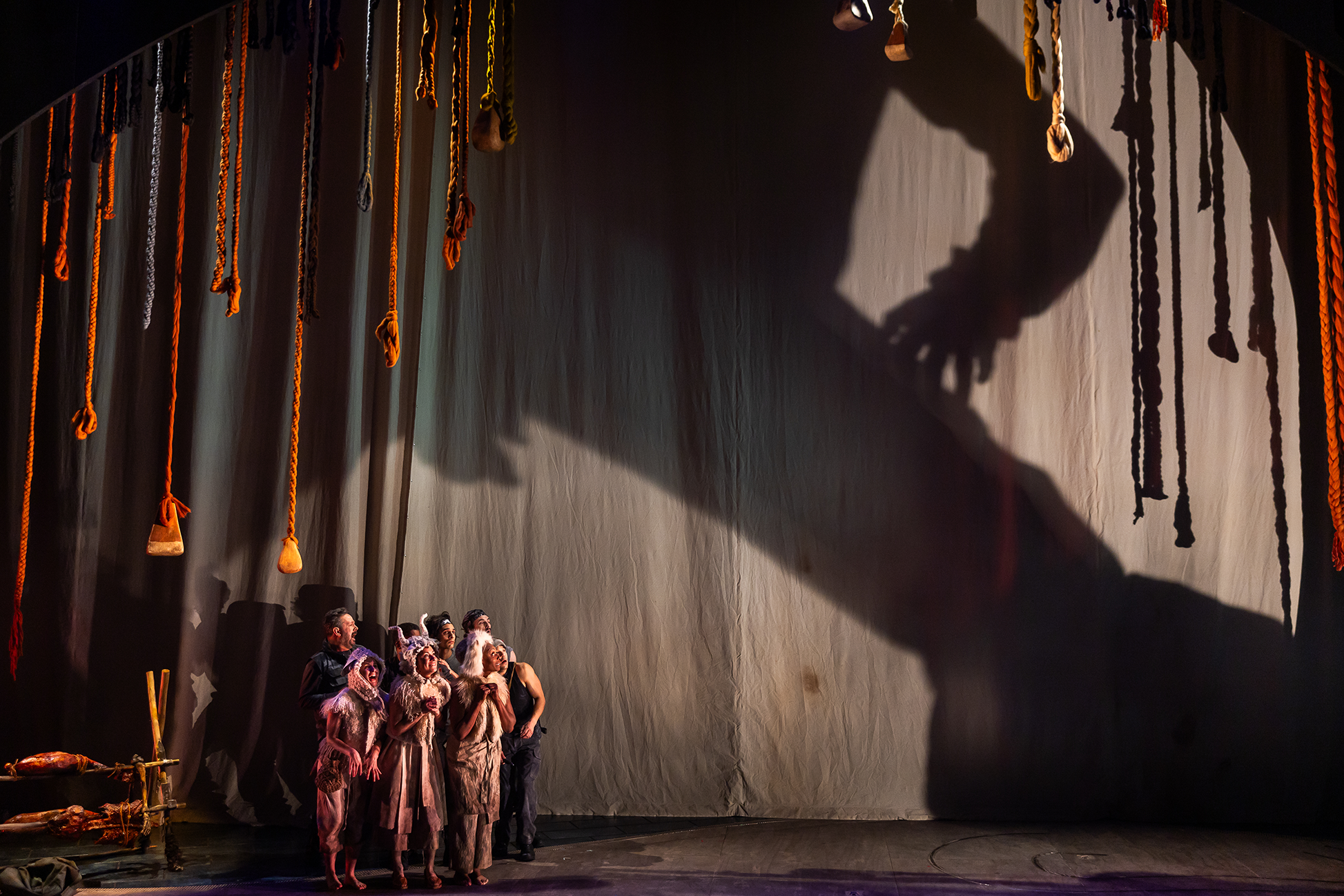

Members of the cast of “The Odyssey.”

Nile Scott Studios and Maggie Hall

Star of new ‘Odyssey’ adaptation? Your imagination.

Puppet designer on power of negative space to provoke emotion — and creating a convincing Cyclops

Kate Brehm knelt behind a backlit screen in a Loeb Drama Center rehearsal room, holding a shadow puppet of the character Penelope from Homer’s “Odyssey.” Brehm and puppeteer Abigail Baird were discussing the movements required to ensure a sharp silhouette of the puppet during a scene in the A.R.T.’s new stage adaptation of the epic poem.

“Part of the skill of puppetry is to offer just enough information, but not all of it, so that you’re taking advantage of the negative space in between so that the audience can fill it in,” said Brehm, puppetry director and designer for “The Odyssey,” which opens at the American Repertory Theater on Feb. 18.

“Puppets are a blank slate in a way, which sometimes allows for more emotional engagement from the audience. I’m very excited about audience imagination, because what the audience can imagine is better than anything I could make.”

The artifice involved in shadow puppetry dovetails perfectly with a production that reflects on the illusions of heroism created by storytelling, said Brehm, lecturer in Physical Theater in the FAS’ Theater, Dance & Media program.

Written by Kate Hamill and directed by Shana Cooper, the adaptation reimagines the stories of Odysseus (played by Wayne T. Carr) and his wife, Penelope (Andrus Nichols), around themes of healing and forgiveness as ways to end cycles of violence and revenge. While most of the play is performed by live actors, puppets are used in several key scenes.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

“I’m intrigued by the non-verbal information that is conveyed through puppetry,” said Brehm, who has been directing, designing, and performing puppetry and experimental theater works for more than 20 years. “You can really tell difficult stories, stories about trauma, like this version of ‘The Odyssey.’ It makes sense to me to express these difficult ideas in something other than the human.”

Take the scene in which Penelope tells her son Telemachus (Carlo Albán) the story of his father’s departure. As many as five cast members are handling puppets behind the screen, including Nichols and Albán, who are puppeteering while also narrating the story. The actors must think about their puppets’ placement on the screen, how the size of their shadows changes with their proximity to light, as well as the emotions conveyed through their movement.

“It’s very much like choreography,” said Brehm, who is teaching a course titled “Puppet Theater” this semester. “There are two performances going on here. One is the performance the audience sees on the puppet screen, and one is the choreography of the actors and puppeteers behind the scenes, picking up and putting down puppets in precise locations.”

“I’m intrigued by the non-verbal information that is conveyed through puppetry,” says Kate Brehm.

Photos by Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

A puppet made of plywood.

One piece of the Cyclops’ eye.

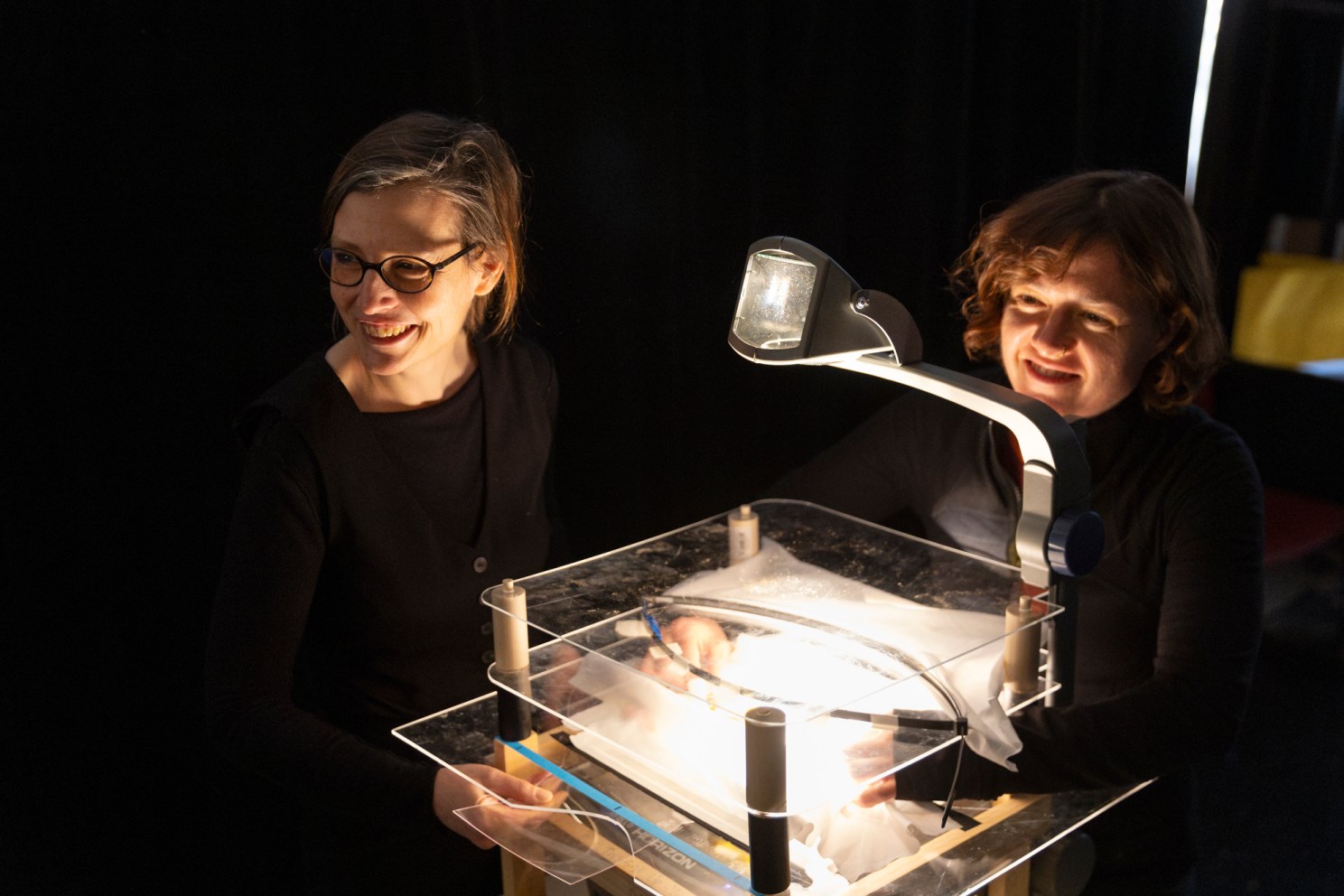

Brehm (left) and Abigail Baird project the Cyclops’ eye.

Brehm uses a different illusion to portray the Cyclops’ eye, which appears when the giant Polyphemus (Jason O’Connell) captures Odysseus and his men. Brehm and Waltham puppeteer Sarah Nolen constructed three tiers of plexiglass above an overhead projector so they could manipulate the Cyclops’ eyelid to make it look like it is opening and closing. The eye, which Baird operates with another puppeteer, must be in sync with O’Connell’s performance.

“You have to breathe together and anticipate, and get to know the other performers,” Baird said, likening the experience to being part of an orchestra.

Brehm worked with Nolen to design and build the puppets. About a foot in length, the handheld shadow puppets are made from a combination of thin plywood, styrene, and acrylic, and some have movable joints constructed with wire.

Brehm sees her puppetry work as just one piece in the larger “puzzle” of the show, which she described as “literally epic.”

“What I hope the audience takes away from this show is a larger vision about the myths we create,” Brehm said. “Our capacity to both make them and to change them within our families and our societies. We have the power to make our own stories.”