How maps (and cyclists) paved way for roads

Map of the road from Dublin to Wexford, circa 1845.

Courtesy of Harvard Library

Curator takes alternative route through cartographic history and finds a few surprises

Today many people would be lost without the interactive, highly mathematical GPS maps that we carry in our pockets. But entire traditions of mapmaking exist outside the norms of latitude and longitude, from routes drawn in sand to itineraries for early traders to topographical guides for the earliest hobby cyclists.

“Rivers & Roads: The Art of Getting There,” an exhibit on display through Jan. 31 in the corridor gallery of Pusey Library, explores methods of mapmaking “that don’t adhere to this latitude and longitude system but are still very effective,” said curator Molly Taylor-Poleskey, Harvard Map Librarian. Taylor-Poleskey spoke to the Gazette about what these unusual maps can tell us about how we think about getting from here to there. This interview was edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to focus on maps that don’t rely on a grid system?

There is a Western tradition of mathematical mapping that undergirds digital wayfinding like what you have on your Google Maps. Other ways of saying this are Cartesian, universal, or Ptolemaic maps, from the ancient Greek mathematician who came up with the idea of placing an imaginary grid over the globe from which you could measure one point to another.

Molly Taylor-Poleskey, Map Librarian at Harvard Library.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

But that’s only one kind of distance, and it’s not the way that I think about distance when I move around in my everyday life. I think, “OK, I’m going to bike to work today. Where are the hills, where’s the dangerous intersections?” Mapping throughout time and in different cultures has approached the question of getting around in so many ways, but we’ve become so used to thinking about mapping in this one way.

We’ve had this idea about accuracy that goes along with math as universally and completely objective. I wanted to say, it’s not objective. A lot of the maps in this exhibit are hyperlocal, and they need to be seen in their contexts to understand what they’re trying to accomplish. I wasn’t interested in the global worldview; it’s really about communication between the mapmaker and the map user. What I found in the process of curating the exhibit was a beautiful variety of ways of doing that.

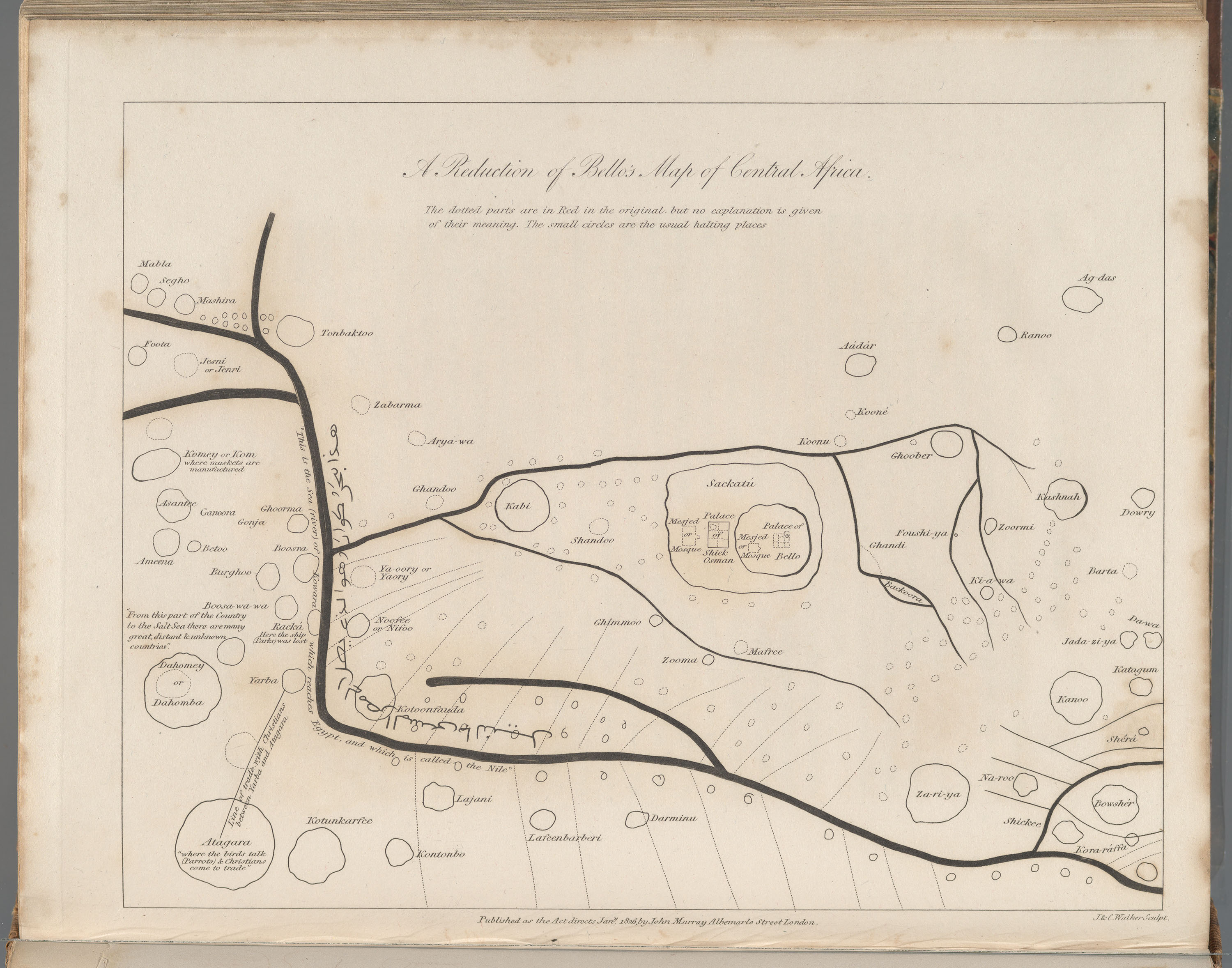

Sultan Bello’s Map of the Niger River’s Course, 1826, misrepresents the river.

Courtesy of Harvard Library

You have on display a map of the Niger River, published in 1826, that was originally drawn in the sand by Muhammad Bello, Sultan of the Sokoto Caliphate, for a British explorer named Hugh Clapperton. You say it’s believed that Bello purposefully misrepresented the river to discourage Europeans from further exploration of the area. What does that tell us about the balance between objective and objectivity in these hyperlocal maps?

Mapmakers are always selective. In that particular map, we know Sultan Bello is giving some misinformation about something he knew quite intimately. We can conjecture about the things he wanted to hold back. Maps are about control of information, so there’s a specificity about what’s useful and what’s not.

I’ll also say that the question of objectivity comes up in another way in the history of mapmaking. Western maps in a certain era would say “There be monsters here,” and that was code for “We don’t know, and what we don’t know is dangerous.”

There’s a switch in about the 19th century in Western maps where you stop seeing what today we think of as ornamental elements. That’s because there’s this idea that people have conquered nature, and it’s not so scary.

What other themes emerged as you put together this exhibit?

Roads started appearing in European maps much later than I would have thought, not until the 17th century. I was curious about what Europeans used for wayfinding before that, and I discovered it was itineraries. It came out of the medieval pilgrimage tradition. You’d convey the route from one place to another by listing the places along the way. In the early modern period, merchants created itineraries showing the routes connecting sites of production to market cities. Those maps didn’t have political boundaries because you didn’t need them. That’s a different perspective than we get 100 years later in the 17th century when rulers were making state-sponsored maps.

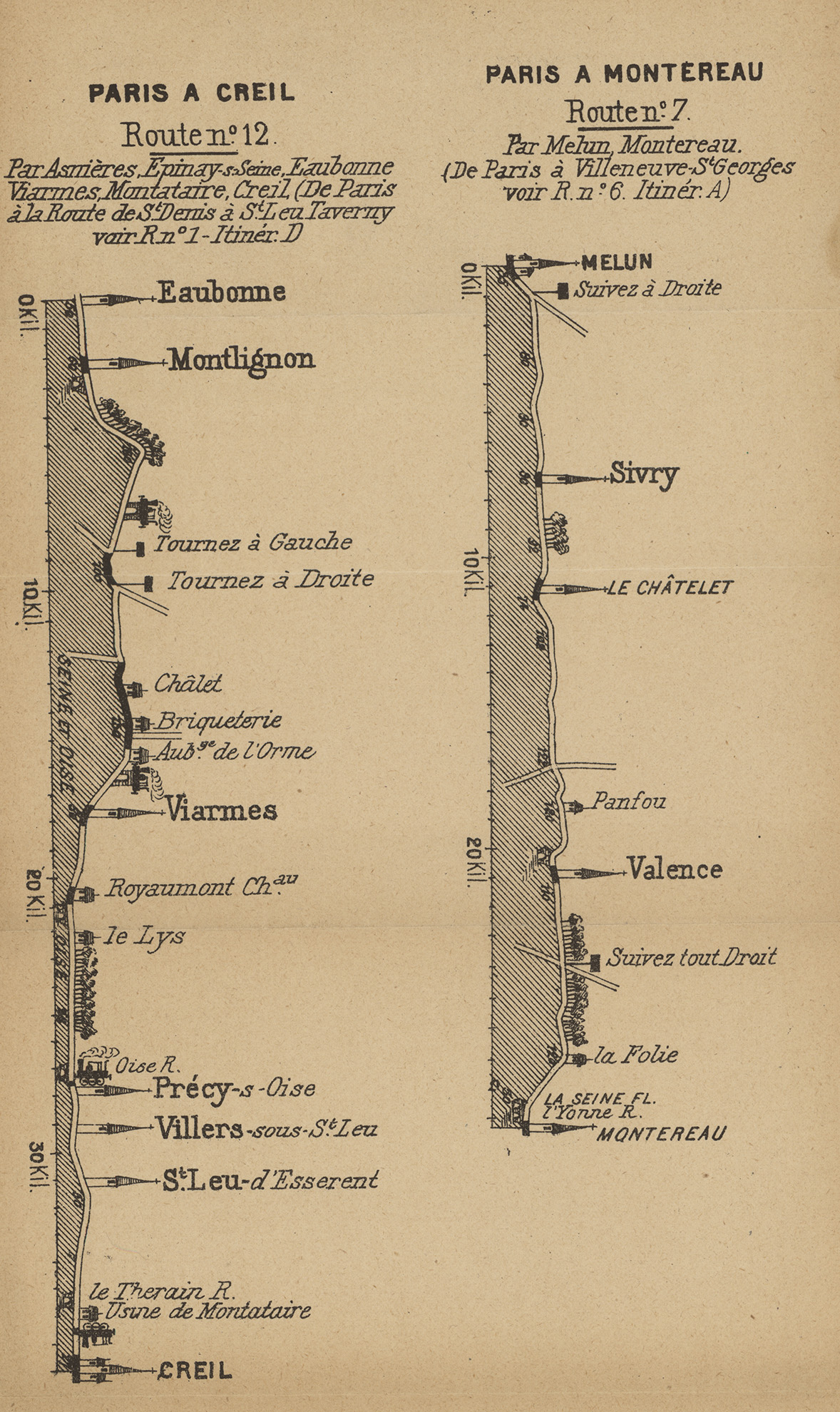

Also, maps don’t just document roads: In a way, they led to the development of roads themselves. In the late 19th century, we have a huge transition. For the first time, there was a middle class in Europe and America that had money and time for leisure activities. At the same time, bicycles become safer and massively popular. You have a lot of newly urban people who are venturing out to enjoy the countryside recreationally. So how do they know how to get around? There are no road signs. This vogue for excursions into the countryside led to the development of route maps that you could fold up and put in your pocket. We have a map of bicycle routes in Paris that shows elevation change because you want to know when you’re going to have to push. It’s so interesting to me because it has some features like a GPS navigation system would have today that say, “turn left,” or “straight ahead.” It’s just one little instruction because you are simultaneously navigating and riding and do not want to be distracted by extraneous information.

Bicycle routes near Paris, circa the early 20th century.

Courtesy of Harvard Library

Hobby cyclists would find themselves lost or broken down with no information about where they were or where they could get help, and the roads were almost all unpaved. So they became huge road advocates. We have an 1888 cyclists’ road book from Connecticut, the first modern tourist guidebook. It was made by the League of American Wheelmen, and they had a campaign for marking roads and systematizing them. That kind of advocacy work in government and through their publications is copied by automobile associations right afterward, which become democratized shortly after. Organizations like the American Automobile Association, AAA, took on the same methods of advocacy starting in the 1920s. It was largely thanks to the Good Roads bicycle movement that early motorists had any passable roads to travel through the American countryside.

A visitor examines a map during a tour of “Rivers & Roads: The Art of Getting There.”

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer