How humans evolved to be ‘energetically unique’

Andrew Yegian and Daniel Lieberman.

Photo by Dylan Goodman

Metabolic rates outpaced ‘couch potato’ primates thanks to sweat, says new study

Humans, it turns out, possess much higher metabolic rates than other mammals, including our close relatives, apes and chimpanzees, finds a new Harvard study. Having both high resting and active metabolism, researchers say, enabled our hunter-gatherer ancestors to get all the food they needed while also growing bigger brains, living longer, and increasing their rates of reproduction.

“Humans are off-the-charts different from any creature that we know of so far in terms of how we use energy,” said study co-author and paleoanthropologist Daniel Lieberman, the Edwin M. Lerner Professor of Biological Sciences in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology.

The paper, published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, challenges a previous consensus that human and non-human primates’ metabolic rates are either the same or lower than would be expected for their body size.

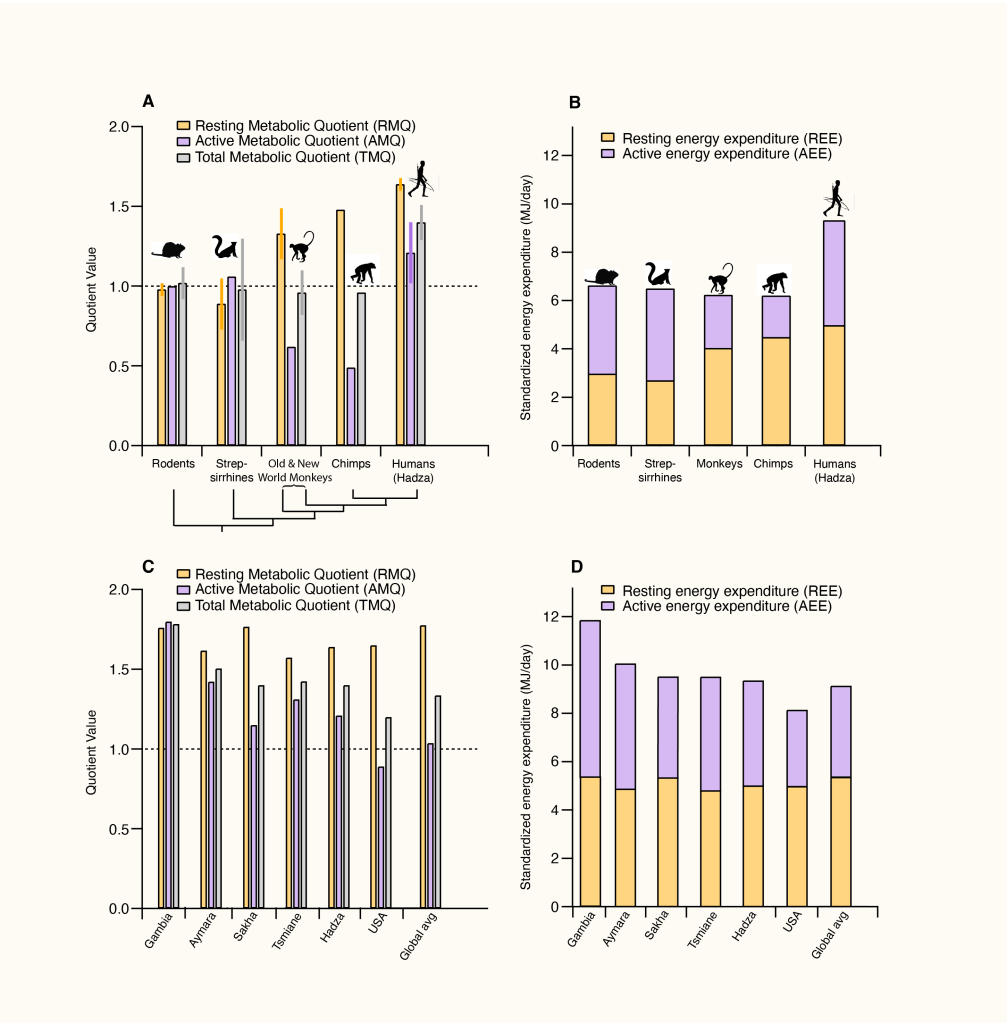

Comparisons of resting, active, and total metabolic quotients among various species and human populations, as defined by the Harvard researchers’ new method.

Credit: Andrew Yegian

Using a new comparison method that they say better corrects for body size, environmental temperature, and body fat, the researchers found that humans, unlike most mammals including other primates, have evolved to escape a tradeoff between resting and active metabolic rates.

Animals take in calories through food and, like a bank account, spend them on expenses mostly divided between two broad metabolic categories: resting and physical activity. In other primates, there is a distinct tradeoff between resting and active metabolic rates, which helps explain why chimpanzees, with their large brains, costly reproductive strategies, and lifespans, and thus high resting metabolisms, are “couch potatoes” who spend much of their day eating, said Lieberman.

Generally, the energy animals spend on metabolism ends up as heat, which is hard to dissipate in warm environments. Because of this tradeoff, animals such as chimpanzees who spend a great deal of energy on their resting metabolism and also inhabit warm, tropical environments, have to have low activity levels.

“Humans have increased not only our resting metabolisms beyond what even chimpanzees and monkeys have, but — thanks to our unique ability to dump heat by sweating — we’ve also been able to increase our physical activity levels without lowering our resting metabolic rates,” said co-author Andrew Yegian, a senior researcher in Lieberman’s lab.

“The result is that we are an energetically unique species.”

“Humans have increased not only our resting metabolisms beyond what even chimpanzees and monkeys have, but — thanks to our unique ability to dump heat by sweating — we’ve also been able to increase our physical activity levels without lowering our resting metabolic rates.”

Andrew Yegian

The team’s analysis shows that monkeys and apes evolved to invest about 30 to 50 percent more calories in their resting metabolic rates than other mammals of the same size, and that humans have taken this to a further extreme, investing 60 percent more calories than similar-sized mammals.

“We started off questioning if it was possible that humans and other primates could have comparatively low total metabolic rates, which other researchers had proposed,” Yegian said. “We tried to come up with a better way to analyze it using quotients. That’s when we hit the accelerator.”

The research team — which includes collaborators at Louisiana’s Pennington Biomedical Research Center and the University of Kiel in Germany — plans to further investigate metabolic differences among human populations. For example, subsistence farmers who grow all the food they eat without the help of machines have significantly higher physical activity levels than both hunter-gatherers and people in industrial environments like Americans. However, all human populations, regardless of activity levels, spend similar amounts of energy for their body size on their resting metabolic rates.

“What we’re really interested in is variation among humans in metabolic rates, especially in today’s world of increasing technology and lower levels of physical activity,” said Yegian. “Since we evolved to be active, how does having a desk job change our metabolism in ways that affect health?”