Jamaica Kincaid in her garden.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Walking children through a garden of good and evil

Jamaica Kincaid’s new book presents history of colonialism, identity through plants that helped shape it

In Jamaica Kincaid’s garden, surprises are common. This summer, a Canada lily bloomed by her front door, while dill, tomatillo, and parsnip cropped up in the vegetable garden — all unprompted gifts from past seasons.

Kincaid, professor of African and African American Studies in residence, emerita, walked through the lush beds of plantings at her Vermont, home, snipping scapes off garlic plants for dinner. The Antiguan American author, who once spent half her year in Cambridge, retired from teaching this spring and is now a year-rounder in North Bennington amid the forests, farms, and covered bridges.

“It’s where I feel most at home, really,” she said. “It’s strange, because I grew up in a seascape and now I’m surrounded by mountains. When I’m at the sea I can’t really think, but when I’m at the mountains, I can think.”

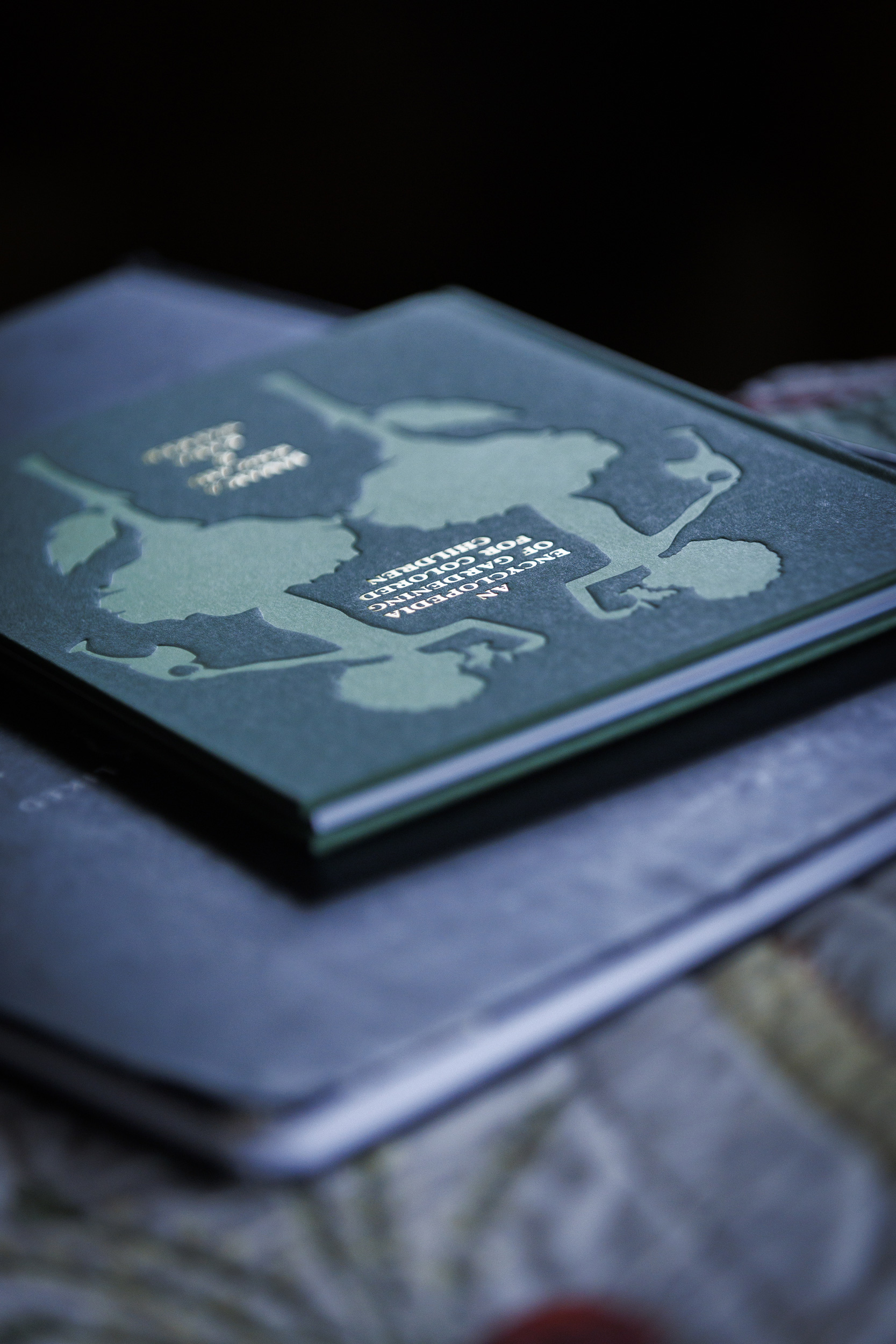

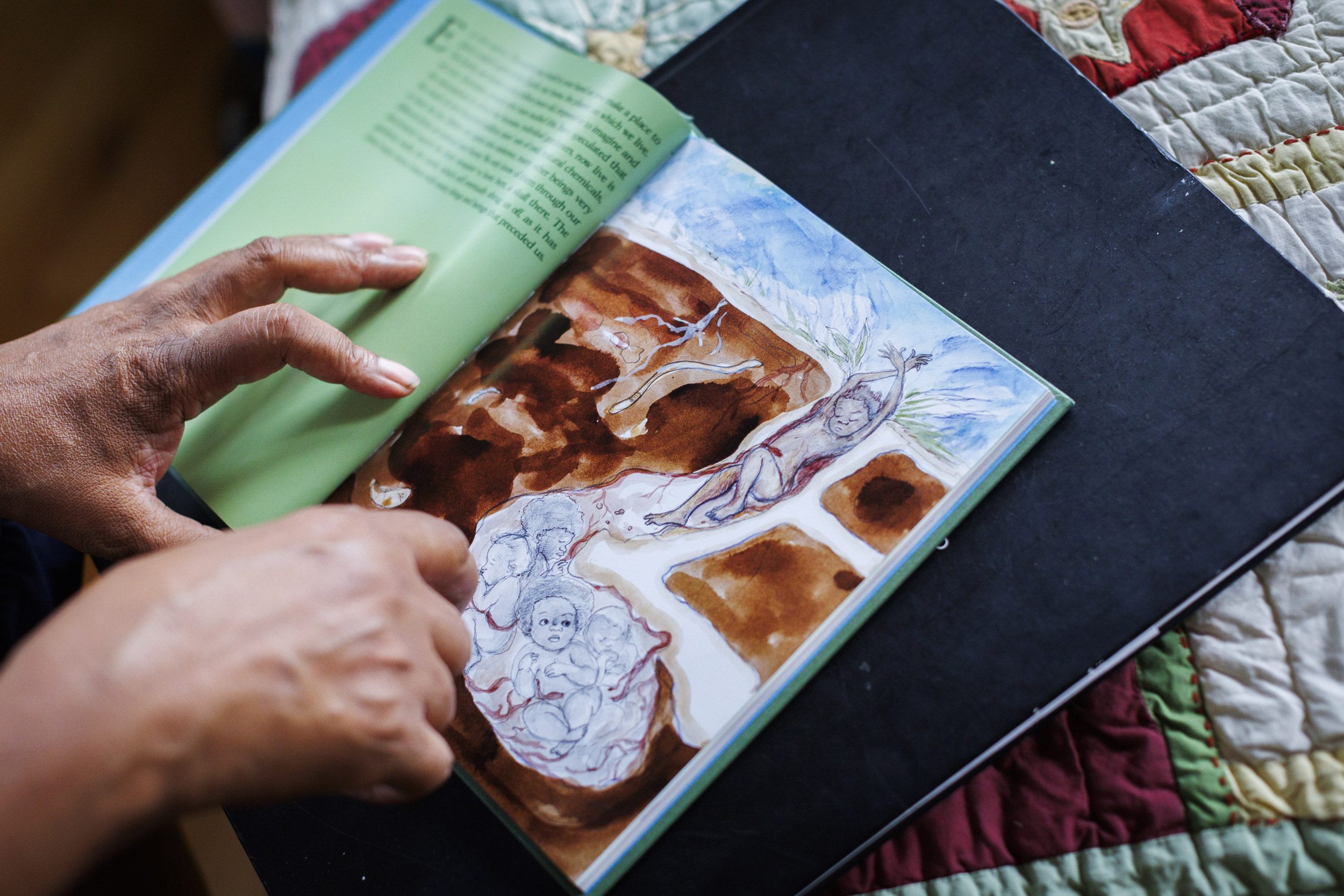

Kincaid shares her love of plants and their history in a new book published this spring. “An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children,” illustrated by Kara Walker, is an ABC of plants that shaped the world, and their often-brutal colonial history. It’s the first children’s book in nearly 40 years for Kincaid, an award-winning writer whose work encompasses themes of colonialism, identity, and family relationships.

“I wrote the book for the child I used to be and perhaps still am.”

“I wrote the book for the child I used to be and perhaps still am,” said Kincaid, the author of “Annie John” (1985), “Lucy” (1990), “The Autobiography of My Mother” (1996), and “Mr. Potter” (2002), as well as numerous other books, short stories, and essays.

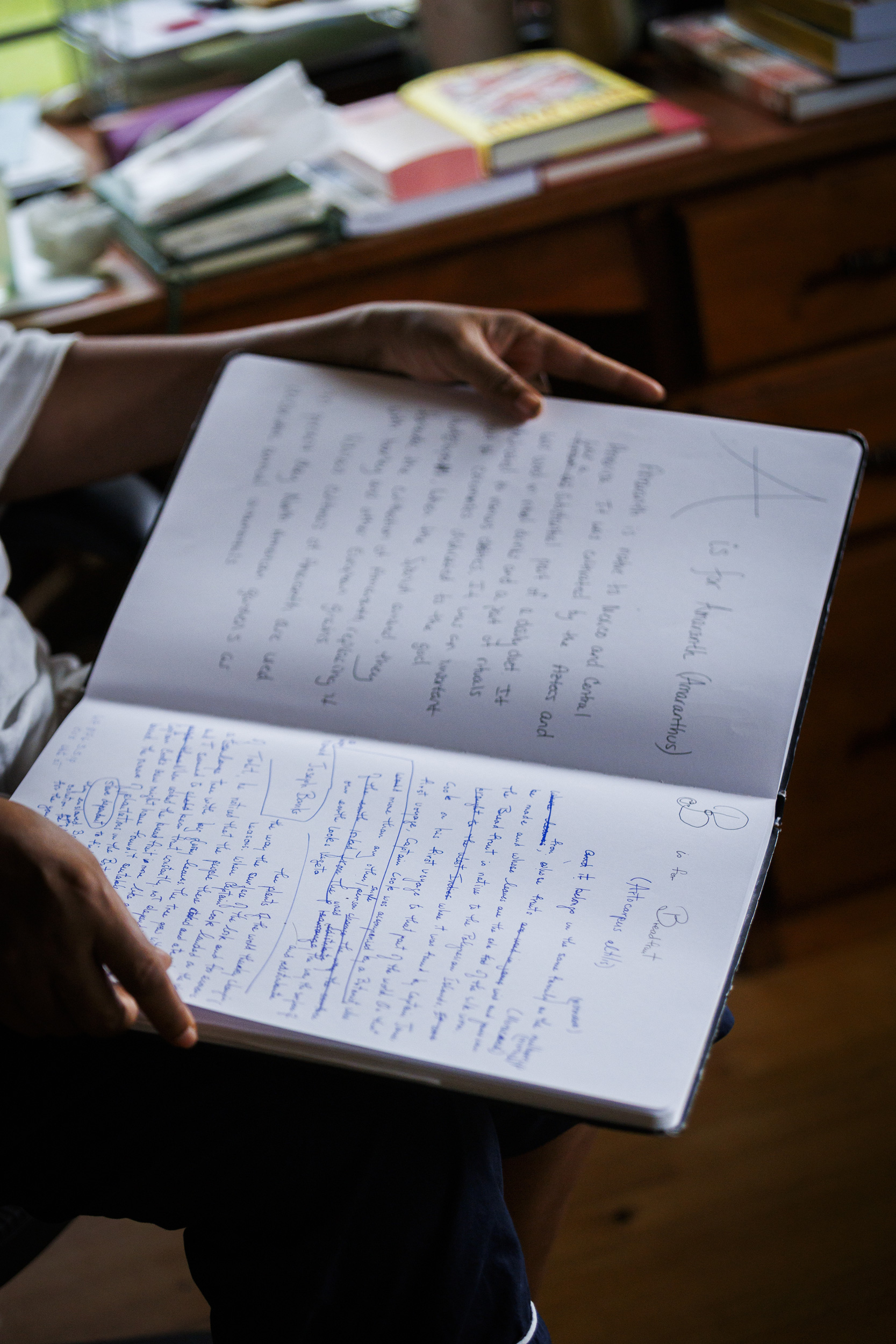

That child learned to read nonfiction books at her mother’s elbow, preferring the dictionary and the Bible to children’s literature. In school, her favorite subjects were botany, history, and geography — three topics she weaves together in “An Encyclopedia.”

As a child in Antigua, Kincaid experienced an island climate dry and prone to drought, but her mother, who came from the more tropical climate of Dominica, had a natural talent for growing plants that Kincaid absorbed.

Today, she said, gardening serves as a way of getting her literary ideas flowing. The writing desk in her Vermont office sits before a wide window that looks out on a magnolia tree and the garden beyond.

Her garden is a patchwork of memories and meaning: two hollyhocks grown from seeds she collected in Ukraine and Israel, a cotoneaster from a visit to China, and a section devoted to Antiguan plants — cotton, sugarcane, banana, cockscomb, and dahlias — which she raises with varying degrees of success in less temperate southern Vermont.

“I didn’t write [my book] to make children interested in gardening, but to be interested in the world,” Kincaid said. “It’s meant to make you love the world. Because I love the world, and the world of the garden in that book.”

“An Encyclopedia” opens in the Garden of Eden (“A Is for Apple and Adam too”), establishing themes of good, evil, and the fall of man, which come up on later pages.

“So much of the garden as we know it, or the vegetable kingdom, is involved in a great violation in our part of the world: the violation of enslaving people and attaching them to plants to yield wealth for somebody.”

“So much of the garden as we know it, or the vegetable kingdom, is involved in a great violation in our part of the world: the violation of enslaving people and attaching them to plants to yield wealth for somebody,” Kincaid explained. “In thinking about the history of Africans in the New World, you can’t help but immediately go to plants. Their presence is associated with cotton and forced labor and eventually they become a commodity like the commodity of cotton and sugar.”

In her book, Kincaid doesn’t hold back from referencing some of history’s darker moments. “B Is for Breadfruit” explains that the tree was introduced to the Caribbean by Capt. James Cook as food for enslaved people. “U Is for Ulmus” describes the elm tree under which William Penn signed a treaty of friendship with the Lenni Lenape Nation in 1682 that lasted only a generation before the Lenape were displaced by European settlers.

“The American Elm was introduced into the American imagination as a plant that represented love and peace,” Kincaid said. “The American Elm began to suffer from a disease, and it’s extinct now. I make the connection that the elm tree, having witnessed the betrayal of this promise, has decided to die.”

During the publishing process, Kincaid was adamant about keeping the phrase “colored children” in the title, preferring it to “children of color” despite it deterring some potential collaborators. However, Kincaid found a kindred creator in artist Walker, who is known for exploring themes of race, identity, and violence, especially via black cut-paper silhouetted figures.

“I would send her my entries, and she would then draw something for it,” Kincaid recalled. “Everything she sent was a delight.”

Kincaid dislikes most children’s books, finding them too simple and patronizing for their young audiences. Exceptions include a few classics such as Margaret Wise Brown’s “Goodnight Moon” and “The Runaway Bunny,” and Beatrix Potter’s “Peter Rabbit.” (Kincaid identifies with Mr. McGregor.)

“Most children’s books are just utter nonsense and really seem designed to blunt a child’s thinking.”

“Most children’s books are just utter nonsense and really seem designed to blunt a child’s thinking,” Kincaid said. “You should tell us about the world. A child should know all of that, because it encourages us as children to seek out the truth.”

Kincaid taught her final course this spring. Retiring, she said, is bittersweet.

“It made me, I think, a better person,” Kincaid said about teaching. “I loved my students. I loved seeing someone flower.”

Kincaid’s immediate plans include writing, reading, cultivating her garden, and following her own curiosity. This summer, she will delve into the history of the Iberian Peninsula in the 15th century, with books on Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, and the Portuguese empire. (Also in Kincaid’s summer to-read pile: Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower,” Sathnam Sanghera’s “Empireland,” and Silvia Federici’s “Caliban and the Witch.”)

“In a way, I love the feeling of not knowing, because the pleasure of then knowing what you didn’t know is so amazing,” Kincaid said. “I don’t resent being ignorant because every time the ignorance is erased it’s so thrilling. God knows there’s a lot in an individual that is ignorant, but if you just keep on, you erase a little bit of it every day.”