This course changed how I see the world

Students from the class “Vision and Justice” include Elyse Martin-Smith (from left), Toussaint Miller, Tenzin Gund-Morrow, Ryan Tierney, Marley Dias, and Anoushka Chander.

Photos by Dylan Goodman; photo illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

A photographer’s love letter to ‘Vision and Justice’

How has visual representation both limited and liberated the definition of American citizenship and belonging? That’s a key question that Professor Sarah Lewis’ class “Vision and Justice: The Art of Race and American Citizenship” aims to answer.

I was lucky to be one of the 50 students out of 200 who got a seat in the course through the General Education lottery administered by the College. I had no idea at the beginning of the semester how deeply the class would alter my photographic eye and perception of the world. It challenged me as a photographer to understand history through the lens of my passion.

Lewis is an art and cultural historian. In addition to the “Vision and Justice” course, she is also the founder of the Vision & Justice civic initiative, which she explains focuses on “original research, curricula, and programs to reveal the foundational role visual culture plays in generating equity and justice in America.” However, “the work in the classroom is the heart of it all,” she said, as she loves “seeing transformation in my students before my eyes. The sense of empowerment, heightened awareness, and joy is like nothing else.”

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis is the John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Humanities and Associate Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard University.

Photo by Dylan Goodman

Dylan Goodman ’25, story author and photographer.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Her primary teaching goal was to “compel” students to understand and see the power of visual culture for justice across disciplines. “How can we define the trajectory of a country founded on the tension between slavery and freedom, liberty and genocide, equality and exclusion?” said Lewis. “We have done it and continue to do it through the work of culture.”

Leaving this course, I find myself thinking of my photographic subjects as collaborators, just as LaToya Ruby Frazier does; I think about how my photographs can be used to create counternarratives and fight for equality, just as Frederick Douglass did. With every click of the shutter, I think about Lewis’ teaching: Visual art matters.

My classmates came from a variety of concentrations and backgrounds, and they took away just as wide a range of lessons. Below, some of them reflected on their time in the classroom.

Professor and student.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

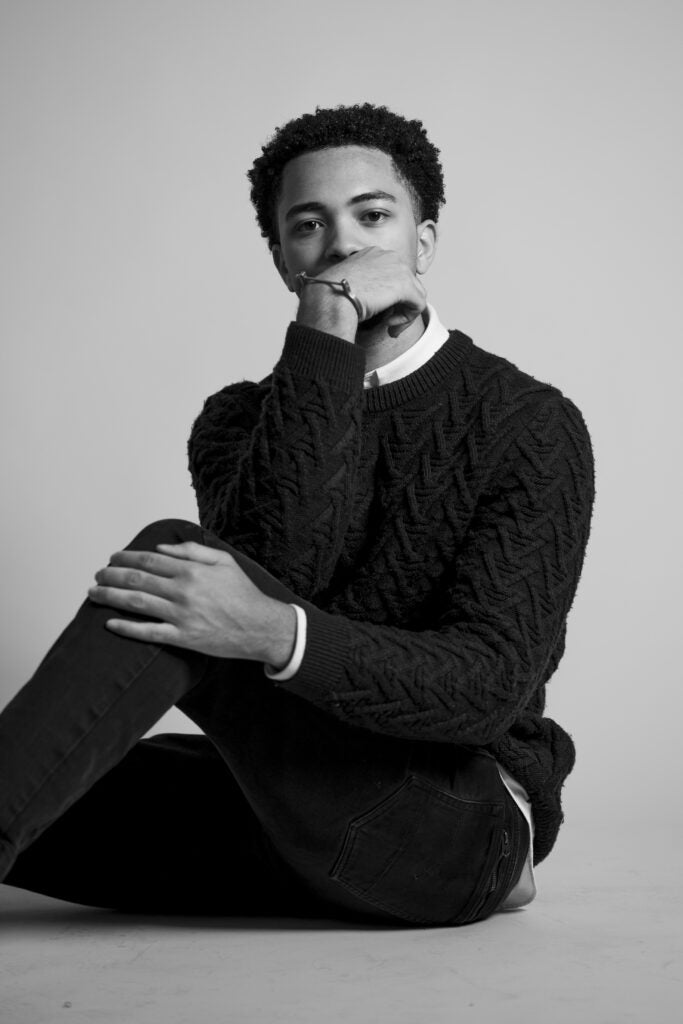

Toussaint Miller ’25

Neurobiology, secondary in music

“The pedagogy of vision and justice is more applicable than it may explicitly seem… As an aspiring surgeon, I could not help but ask how these ideals — rooted in eugenics and polygenesis — have influenced modern medicine. How do the practices of the 18th and 19th century contribute to the health disparities affecting marginalized communities even still today?”

Toussaint Miller

Miller enrolled in “Vision and Justice” for two primary reasons: He believes in the power of representation in defining who we are and what we will become, and he wanted the opportunity to discuss the legacy of art and culture with his peers.

The course has “armed me with the tools necessary to intellectually consider the underlying meanings and contexts of visual art,” he said, noting that he sees visual art as a way to honor human life and denigrate it. A standout moment from the class was discussing how Confederate monuments have come to be the “new battleground of racial contestation” and help us understand how America’s past affects its future.

Marley Dias ’26

Sociology and data analytics, secondary in African American studies

Photo by Dylan Goodman

“While I thought that American history could be divided into racial history, Professor Lewis has taught me the way these histories are constantly intertwined and has pushed my thinking toward seeing cultural movements as essential mechanisms for justice in America.”

Marley Dias

Dias enrolled in this course because of her passion for representation in media. As the founder of the #1000BlackGirlBooks campaign, an international movement to collect and donate books with Black girls as the main character, Dias believes capturing the “full spectrum of identity can heal the wounds of our oppressive history.”

Dias said the course changed the way she understands race. She learned how to use visual analysis and historical context to understand how sight plays an integral role in race, especially in how we can challenge oppression.

Ryan Tierney ’24

History and literature, secondary in economics

“As a second-semester senior, I expected that I would be ‘cruising to the finish line,’ having already experienced all of the perspective-shifting classes of my College career. I was so wrong, and I have been profoundly impacted by this class.”

Ryan Tierney

Tierney said he loved the discussions Lewis led, explaining that “the way in which she amplified everyone’s perspective was really helpful to our overall understanding … When it comes to art and images, perspective matters.”

He defined the course as centering around changing the way individuals view representation in the U.S.

Elyse Martin-Smith ’25

Social studies and African American studies

“I love that this GenEd brings together people from many different areas at the College. As someone who focuses in Black Artivism (arts and activism), it is enlightening to examine the shared struggle of other marginalized communities, exploring deep parallels and linked fate.”

Elyse Martin-Smith

Martin-Smith enrolled in the class because of her passion for the arts, primarily music, in honoring the traditions of Black people.

Martin-Smith enjoyed the lectures, engaging with guest speakers, materials from the Harvard Art Museums, and the process of hearing classmates grapple with their own opinions on the content. She said she felt inspired to “take action” and “challenge harmful histories” from what she learned.

Tenzin Gund-Morrow ’26

Social studies

“‘Vision and Justice’ has gifted me the language to more exactingly analyze, understand, and explain the issue of citizenship and race in America. It’s provided me with the critical visual skills that are more useful than ever in our modern digital age.”

Tenzin Gund-Morrow

Gund-Murrow had heard that “Vision and Justice” was “one of those special classes that explodes how you see the world.” It changed the way he saw himself as well. Lewis has “forever altered the trajectory of my studies by elucidating the inextricable tie between visual culture, political identity, and public policy.”

Gund-Morrow, who has a scholarly interest in criminal justice, said the class forced him to question the role media and visual artifacts play in the modern carceral system.

He was most struck by the unit on lynching. He said he learned lessons about the “liberatory potential of Black contemporary artists” in addressing its legacy.

Anoushka Chander ’25

Social studies and African American studies

“The class asks us to understand that visual culture — through art, photos, and monuments — has created a narrative of who does or does not count in American life.”

Anoushka Chander

In high school, Chander interned with the Smithsonian Institution museums. She had always viewed these artistic spaces as a place for fighting social injustice. “Museums reckon with ugly histories of oppression, celebrate the beauty and resilience of diverse Americans, and challenge racist beliefs,” she said. Additionally, as a singer and performer, she has always been interested in how art can further representation.

Chander connected the course to her concentration, focusing especially on visual representations of Black motherhood. “In my midterm paper, I discussed how Serena Williams’ pregnant cover photo of Vanity Fair presented Black motherhood as powerful and beautiful, challenging racist assumptions.”