Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Just one family’s history – and the world’s

Claire Messud’s autobiographically inspired new novel traces ordinary lives through WWII, new world orders, Big Oil, and rise and fall of ideals

During World War II, as Nazi troops advanced on France, Claire Messud’s grandfather, a French naval attaché based in Greece, penned a letter to his children to be opened if he did not survive the war.

“It is important for you to know,” he wrote, “we are Mediterranean; we are Latin; we are Catholic; we are French.”

Messud, who is North American and a non-practicing Protestant was struck by the expansiveness of the divide in identity and values between relatives just two generations apart.

“I was suddenly realizing that the world in which I had been brought up and the ideals that had been instilled in me in an unthinking way, now seemed historical to my children, and seemed of a bygone moment,” she said.

Messud, Joseph Y. Bae and Janice Lee Senior Lecturer on Fiction, tackles these generational identity shifts in her new novel, “This Strange Eventful History.” The saga, inspired by Messud’s family history, follows three generations of the Cassar family from 1940 to 2010.

Claire Messud’s aunt Denise Messud, grandmother Lucienne Messud, and father François-Michel Messud, pictured in 1940. They inspired characters in her new novel.

Photo courtesy of Claire Messud

Patriarch Gaston Cassar, his devoted wife, Lucienne, and their children, François and Denise, are “pieds noirs,” people of French origin living in Algeria during French colonial rule. The family leaves the country amid the Algerian War of Independence, and their story grapples with rootlessness, sense of culture, and belonging.

“One of the feelings that I had as I was working on this novel was a Zelig-like sense that this little family of no consequence in the wider world was encountering the forces of history at every turn,” Messud said of the Cassars, whose lives span World War II and its aftermath, the rise of oil (and the climate crisis), and the spread of English as lingua franca.

“This idea that where we are now doesn’t come out of nowhere,” Messud said. “Even 70 years ago the patterns were beginning that have shaped the lives and the challenges that we have now.”

Messud has authored six other works of fiction, including “The Emperor’s Children,” “The Woman Upstairs,” and “The Last Life,” which was also inspired by family history.

“I’ve often felt that I have a faith in stories,” Messud said. “The things that we read shape us and change our lives. Even when we don’t fully remember them, we internalize them and the characters that we’ve loved or hated or grappled with become part of a world in our heads that shapes how we understand the world.”

The Cassars are inspired by her grandparents, parents, aunt, and even herself. When 8-year-old François writes his father a letter, telling him that the Germans have invaded Paris, it’s modeled after one Messud’s father wrote as a boy in 1940. Gaston’s visit to an oil drilling site in the Sahara Desert reimagines a similar one Messud’s grandfather took in 1953.

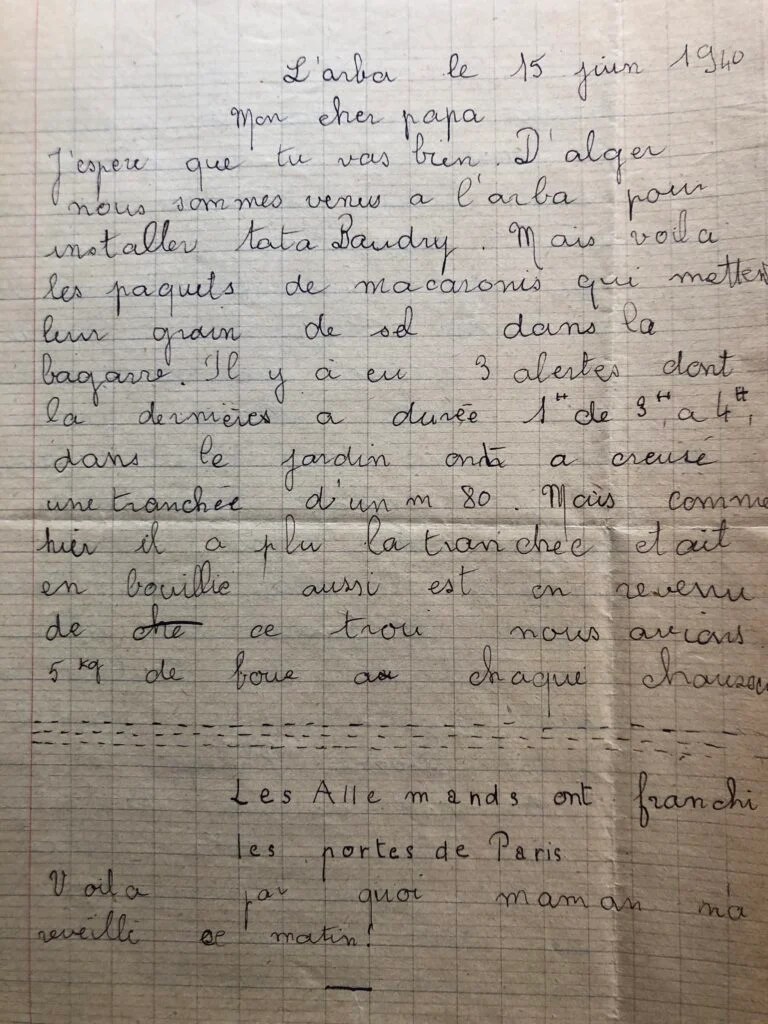

A handwritten letter dated June 15, 1940, sent from Messud’s 8-year-old father to his father. The second-to-last line of the letter says, “The Germans have crossed the gates of Paris.”

Photo courtesy of Claire Messud

Messud also wanted to capture the optimism many families felt at the end of World War II, a belief that the future was cosmopolitan, a dissolving of national, racial, bordered identities. It’s a worldview that later generations have had a difficult time conceptualizing, Messud believes.

“In 1989 when the wall came down and the Soviet Union was dissolving, people thought, ‘All wars will end now,’” Messud said. “We really hoped that the world would be entering a new and better time. And that seems pretty far away now.”

The novel’s final pages reveal a shocking taboo in Gaston and Lucienne’s marriage — one that did not perturb them since their marriage was approved by the pope and considered “ordained by God.” Messud uses this example of blind religious faith to draw a comparison to colonialism — something else previous generations unquestioningly accepted.

“There was a sense not only that it wasn’t a bad thing, but that the colonial project brought good things,” Messud said. “We have the opposite perspective now, and that too is part of the story. These were people, as we all are, born into the beliefs of their times.”

Messud said this book felt “different” from past projects, as it allowed her to feel close to her late family members as she was writing.

“They’re all gone now, and at the time I was writing, they weren’t.”

“They’re all gone now, and at the time I was writing, they weren’t,” she said. “It was a joy to be with them and to be trying to understand their thoughts. It felt like the opposite of passing judgment.”

The character in the novel who most resembles Messud is Chloe, the Cassar granddaughter, who is the narrator of her own sections. Chloe says in the prologue her goal as a writer is to “save life.” Messud agrees.

“Being a writer, for me, feels like taking seawater between my hands and trying to run up to the top of the beach — the water is running through my hands the whole time,” Messud said. “What is life like? What is it like to be a person on the planet in a time in a place? It’s an endless curiosity about what it’s like to be alive.”

Get the best of the Gazette delivered to your inbox

By subscribing to this newsletter you’re agreeing to our privacy policy