Portrait of the artist as a working mother

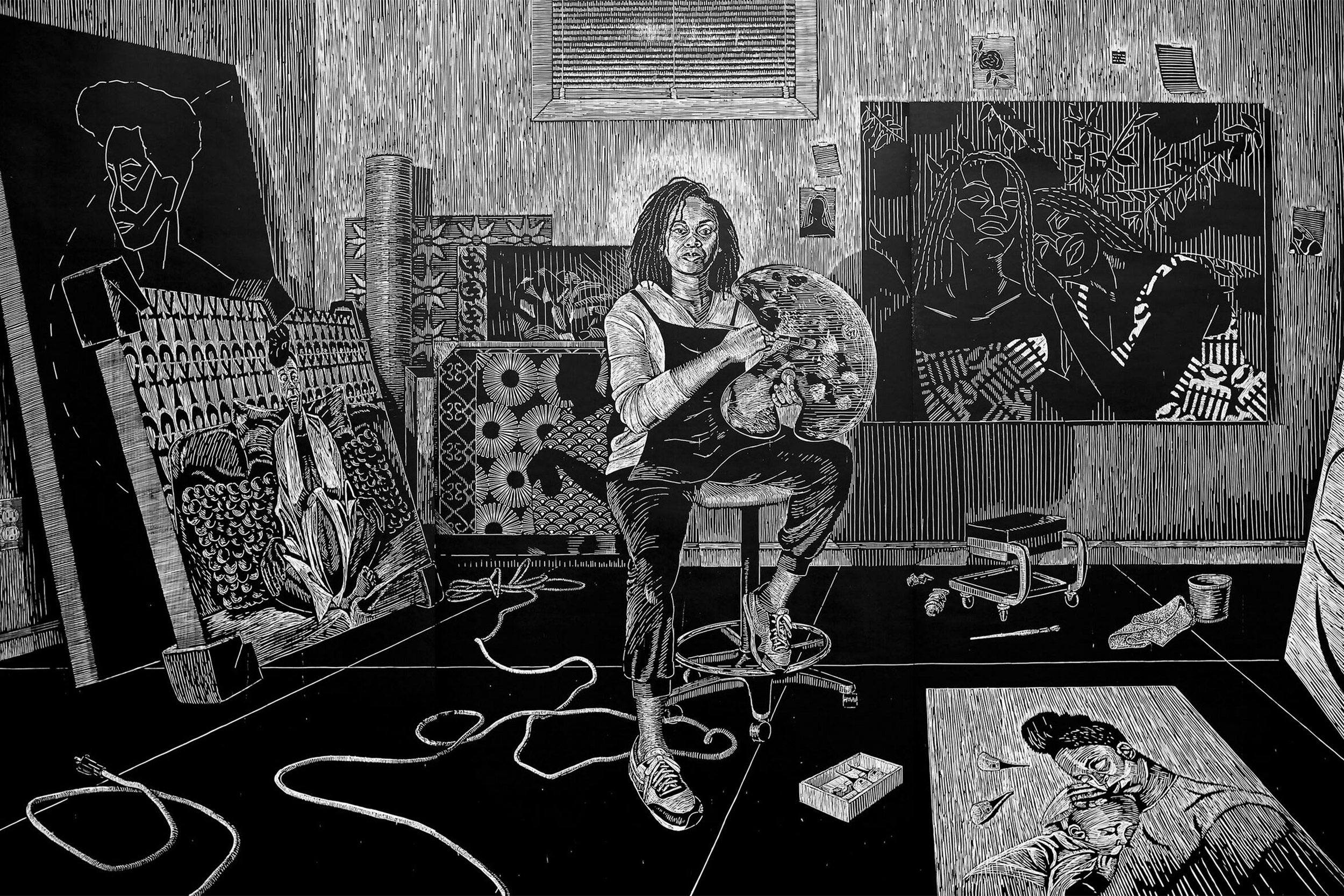

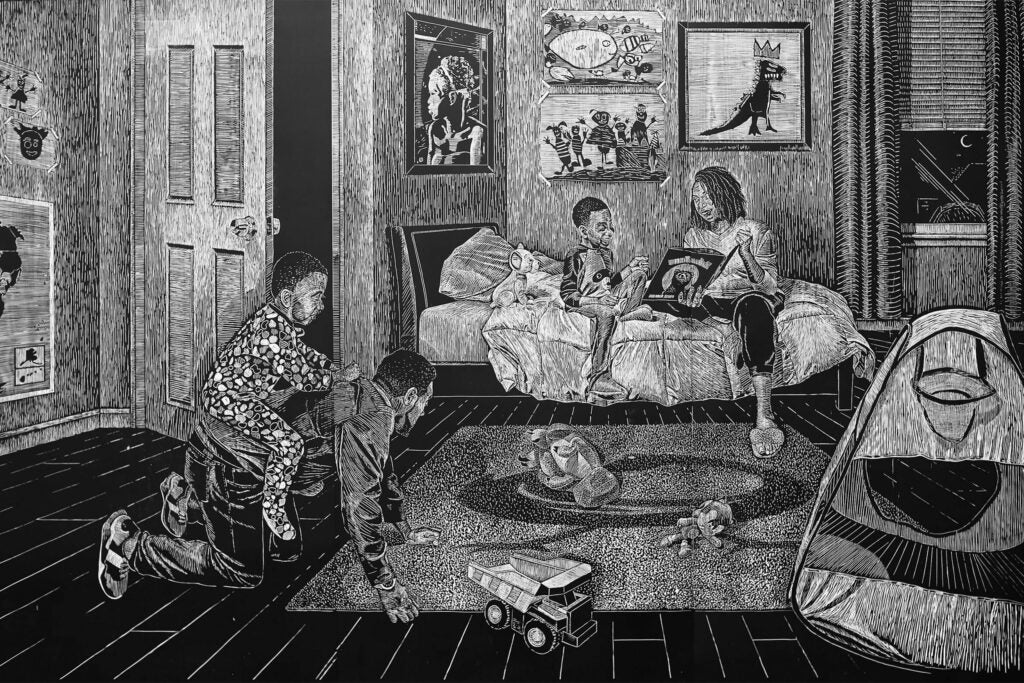

“The Studio” from “Carving Out Time,” 2020–21, woodcut on cotton paper.

Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2022.224.5 © LaToya M. Hobbs Photos by Ariston Jacks; courtesy of the artist

LaToya M. Hobbs made ‘Carving Out Time’ literal

Laundry and lesson plans, meals and bedtime stories can dominate the lives of parents of young children. For printmaker LaToya M. Hobbs, the busy-ness of family life also provided inspiration for a stellar new exhibit: “LaToya M. Hobbs, It’s Time.”

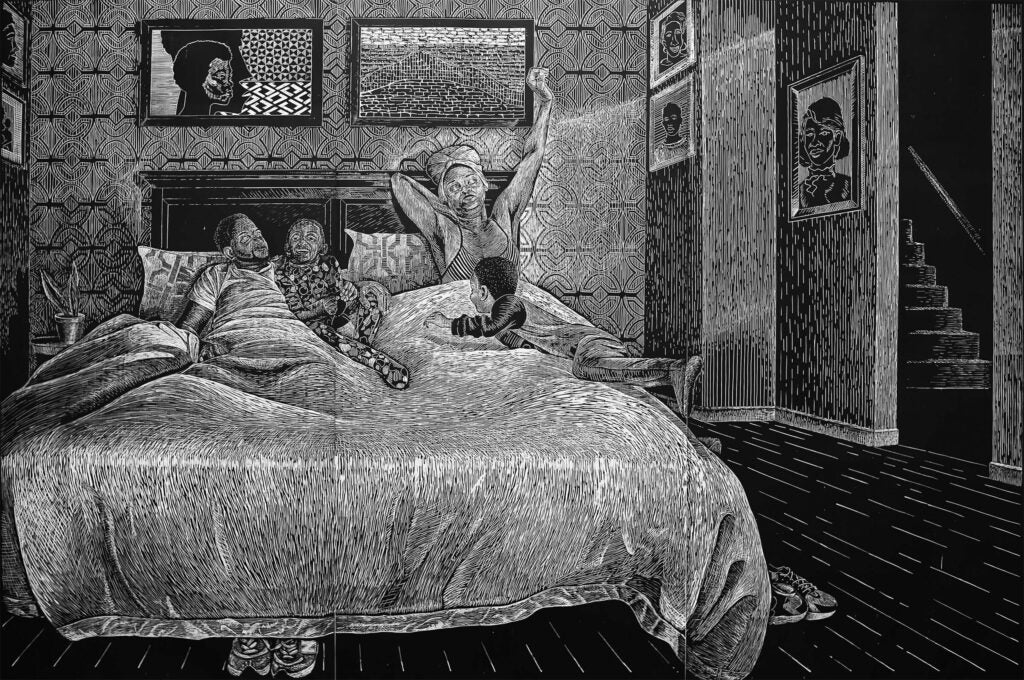

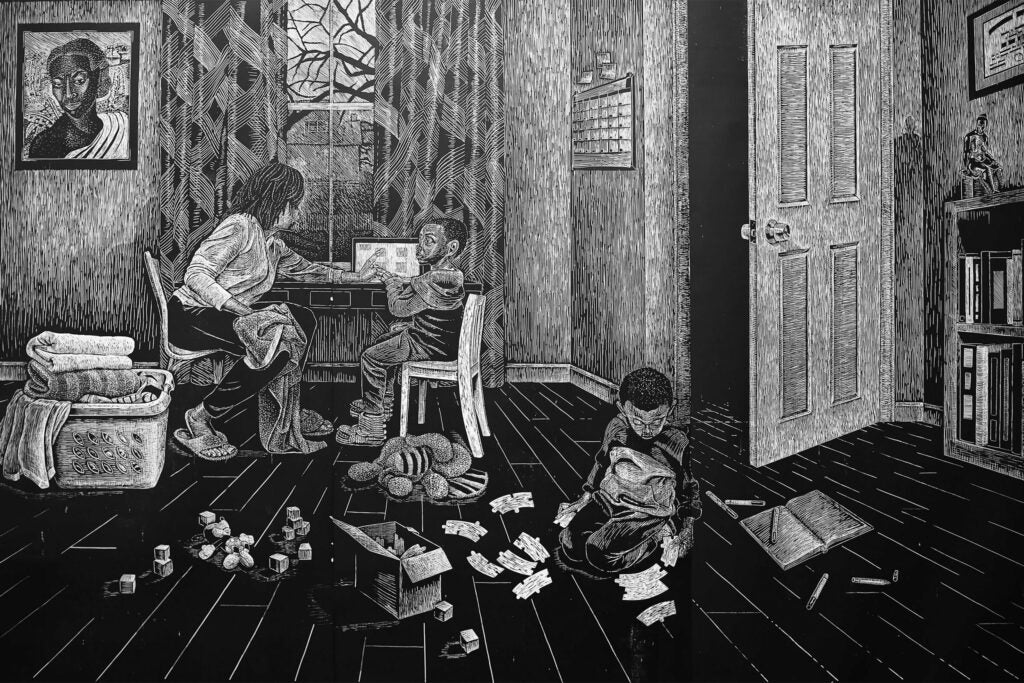

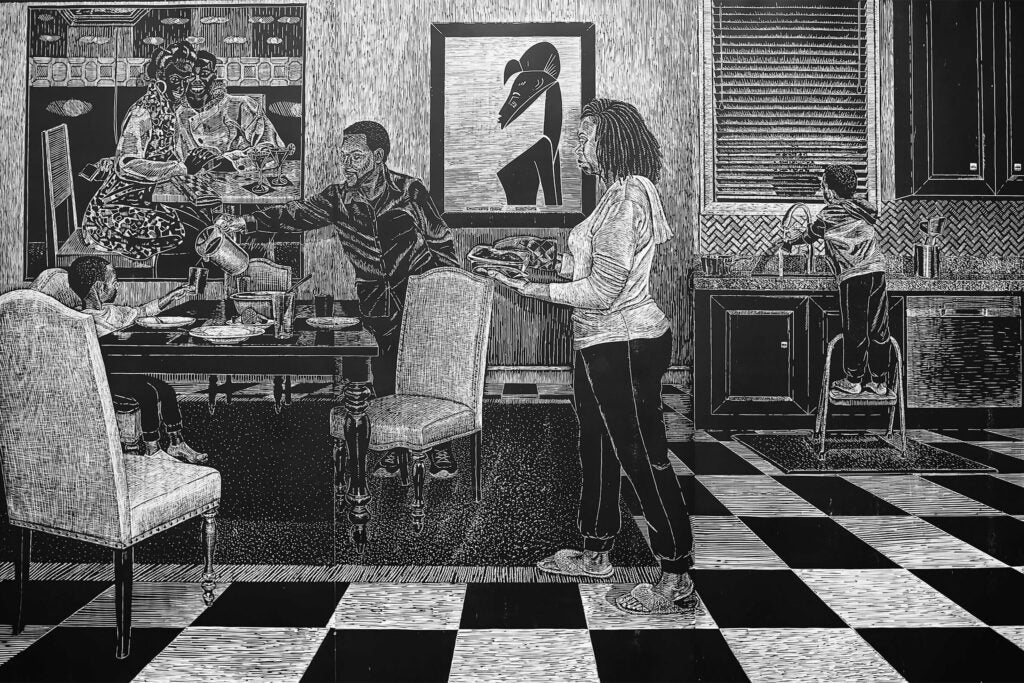

On view at the Harvard Art Museums through July 21, the inaugural presentation is a suite of five 8-by-12-foot prints collectively titled “Carving Out Time.” The climax of Hobbs’ ongoing “Salt of the Earth” series, these towering woodblock prints, which were acquired by the Harvard Art Museums in 2022, fill three walls of the Special Exhibits Gallery. Augmented by preparatory drawings and a video showing Hobbs at work, the pieces present life-size scenes from the domestic life of the artist. Starting with the family waking (“Morning”), they move through “Housework and Homework,” “Dinnertime,” and “Bedtime for the Boys,” until finally Hobbs, the central subject, gets some time alone in “The Studio,” where she can create.

The concept of “carving out time” will be familiar to any working parent, or perhaps any adult who seeks creative or “me” time while balancing other responsibilities. In Hobbs’ case, it’s quite literal. Although the Baltimore-based artist also paints and works in mixed media, this series is made up of woodcuts, a medium in which she literally carves into wood blocks to create images that will be inked and printed.

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2022.224.1 © LaToya M. Hobbs

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2022.224.2 © LaToya M. Hobbs

Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2022.224.3 © LaToya M. Hobbs

Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2022.224.3 © LaToya M. Hobbs

Exposed to the medium as an undergraduate at the University of Arkansas, Hobbs (who was born in Little Rock) described woodcuts as “the first medium I fell in love with.”

“I very much enjoy the tactile quality” of woodblock printing, she said, citing “the carving and the texture.” In its presentation of her creative efforts, the final panel of the series shows the gouges she uses to dig into the wood as well as some of her mixed-media pieces. Even when these tools aren’t shown, the physicality of the form is apparent. Because of the size of the blocks needed to print such large pieces, for example, each of these monumental prints is actually a triptych, made up of three smaller prints from three separate blocks, seamlessly attached.

Despite the starkness of the black-and-white prints, they are suffused with light. With subtle lines or cross-hatching — and especially the use of directional light sources — “The depiction of light and the use of light and shadow” has become “very important in my work,” Hobbs said. Citing Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro (“light and shadow” in Italian) as an influence, she described using light “to create a sense of volume and the illusion of three-dimensionality.” In “Studio,” a ring of light sets off the artist’s head with a subtle halo. In “Morning,” sun shines in thanks to a “happy mistake,” when Hobbs “picked up the wrong size tool” and gouged too deeply, leaving a lighter area, an accident she utilized in the finished print. “You can see the day is starting, so light is starting to seep into the room,” she said.

Art itself is present throughout this series as well, with paintings and sculptures depicted on walls and shelves, drawn from what Hobbs calls her “dream collection” by noted contemporary Black artists such as Margaret Taylor-Burroughs, Elizabeth Catlett, Kerry James Marshall, and Valerie Maynard. Included as well are drawings by Hobbs’ two young sons, such as a delightfully whimsical drawing of fish and another of a birthday party that take centerstage in “Bedtime.” More than just decorative, these pieces reflect the life from which they draw, at times literally, as when the stylized silhouette of Maynard’s “senufo” is mirrored by Hobbs’ tired slouch in “Dinnertime.”

“You can’t be an artist and not have work in your home,” Hobbs said. In addition to curating their own space, she and her husband, Ariston Jacks (also a visual artist), are conscious of the role art plays in their children’s lives. In addition to fostering a love of art and “an appreciation of the things that other people make,” she said, “we always want our children to be able to see a reflection of themselves and aspects of their culture, particularly in our home.”

In keeping with this theme, “Carving Out Time” incorporates children’s activity guides as well as public events conceived by a group of Black women undergraduates, which includes print-making workshops, a “StoryTime for All Ages,” and more. The exhibit is presented alongside “Future Minded: New Works in the Collection,” a gorgeous and wide-ranging gathering of new acquisitions: photography, prints, paintings, and sculptures by artists such as Willie Cole, Toyin Ojih Odutola, and the indigenous artist Jeffrey Gibson, who is representing the U.S. in the 2024 Venice Biennale.