One of few dozen Black students on campus, he brought his camera everywhere

Former yearbook editor donates two boxes of images of College life from his perspective in turbulent mid-’60s

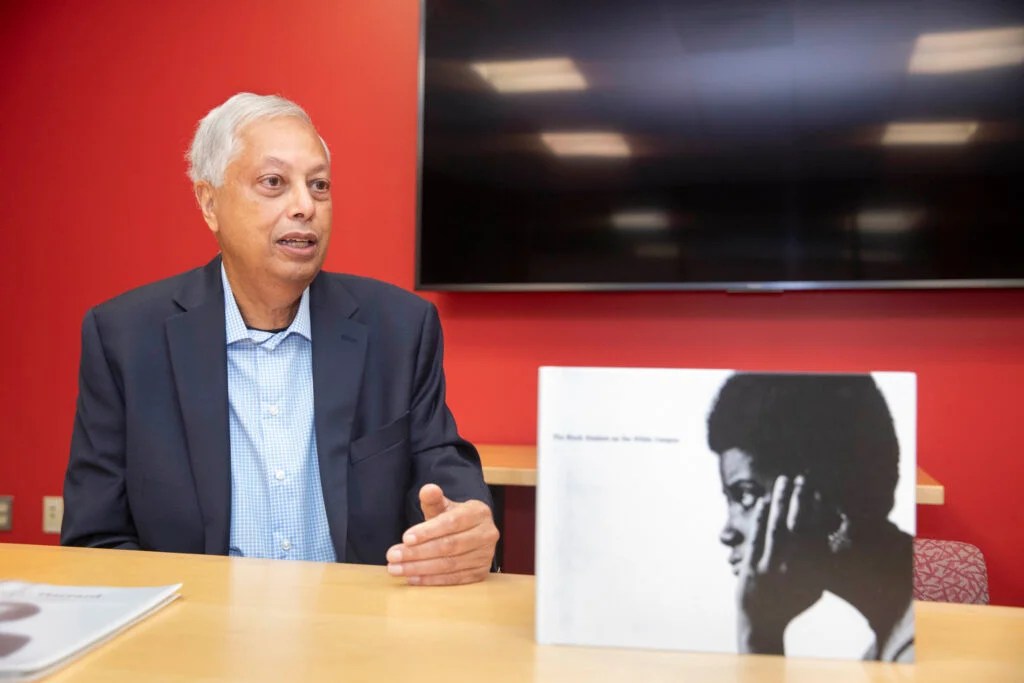

Lee Smith ’69, the Harvard Yearbook’s first Black managing editor, has donated many of his photos from his time on campus to The Harvard University Archives.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Lee Smith had been moving two metal bankers boxes of photo negatives from apartments to houses and across state lines since graduating from the College in the late 1960s. The archival-quality images, tucked into glassine envelopes, chronicle the four years of his time at Harvard, three of which were spent as a yearbook photographer and all of it during a time of upheaval in the nation.

“They really represent a time capsule of history that I was in,” Smith said. “It didn’t make any sense to throw them away.”

The Department of African and African-American Studies and The Harvard University Archives are glad he felt that way. Last spring Smith donated his negatives to the Archives, which is currently working to digitize them to make them available to researchers and others, a timely addition given that next year marks the 75th anniversary of Harvard Yearbook Publication’s annual compendium.

“While the Archives’ collections include important visual and photographic resources, many represent an official, institutional perspective, so we were particularly excited at the opportunity to acquire such a rich collection that documents a pivotal time at Harvard from the perspective of a gifted student photographer,” said Juliana Kuipers, associate University archivist for Collection Development and Records Management Services.

Smith, a kid from mostly Black South Dallas who had spent his last year of high school at the prestigious, and mostly white, St. Mark’s preparatory school in Texas, arrived in Cambridge at a time of rapid social change both on campus and off.

Smith began college during the Vietnam War and shortly after the signing of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination based on race, religion, color, sex, and national origin in vast swaths of American life, including education, employment, and public accommodations.

“Integration was as much for the white students who were there to have a Black experience they never had, or were deprived of, if not more than for the Blacks to come and have access to perhaps a superior education with various resources and teachers and things like that,” Smith said.

On campus he found himself at a unique intersection of fitting into a lot of places where others were standing out. Smith recounted the story of another student who lived in Wigglesworth alongside him in his first year. He said that student struggled to adapt to Harvard life and often sought refuge in Boston’s Black neighborhoods like Roxbury.

“Because I spent a year at St. Mark’s I learned some things about what I needed to not look for in people in terms of my needs,” Smith said. “And I’m really well-grounded and also very social. I can be sort of a chameleon — I can get along with people that have various differences.”

Smith stepped onto campus with his dad’s old Praktica and a restless curiosity about the world. In high school he had developed the habit of taking a camera everywhere he went.

Smith stepped onto campus with his dad’s old Praktica and a restless curiosity about the world. In high school he had developed the habit of taking a camera everywhere he went.

Smith said there were roughly 30 Black students when he first arrived. His sophomore year, during which Smith was enticed to join the yearbook by promises of unlimited film and darkroom access, there were somewhere around 45. Students were calling for Black studies and curriculum. Smith engaged with AFRO — the student African American Resistance Organization.

“I wanted to create the time capsule of what that experience was like. I wanted them to have a voice and I wanted history to be there,” he said. “And because of my position with the yearbook, I could leverage that.”

Smith got photos of various luminaries on campus, including now-legendary Black leaders such as politician Julian Bond and activist Whitney Young (who was captured meeting Black students in Winthrop house). He took shots of The Temptations playing during his freshman year and Dionne Warwick when she came.

“I wanted to create the time capsule of what that experience was like. I wanted them to have a voice and I wanted history to be there. And because of my position with the yearbook, I could leverage that.”

Lee Smith

Smith covered a 1968 Class Day address by Coretta Scott King praising the effectiveness of student activism on campus. King was substituting for her husband, Martin Luther King Jr., who had been assassinated two months before.

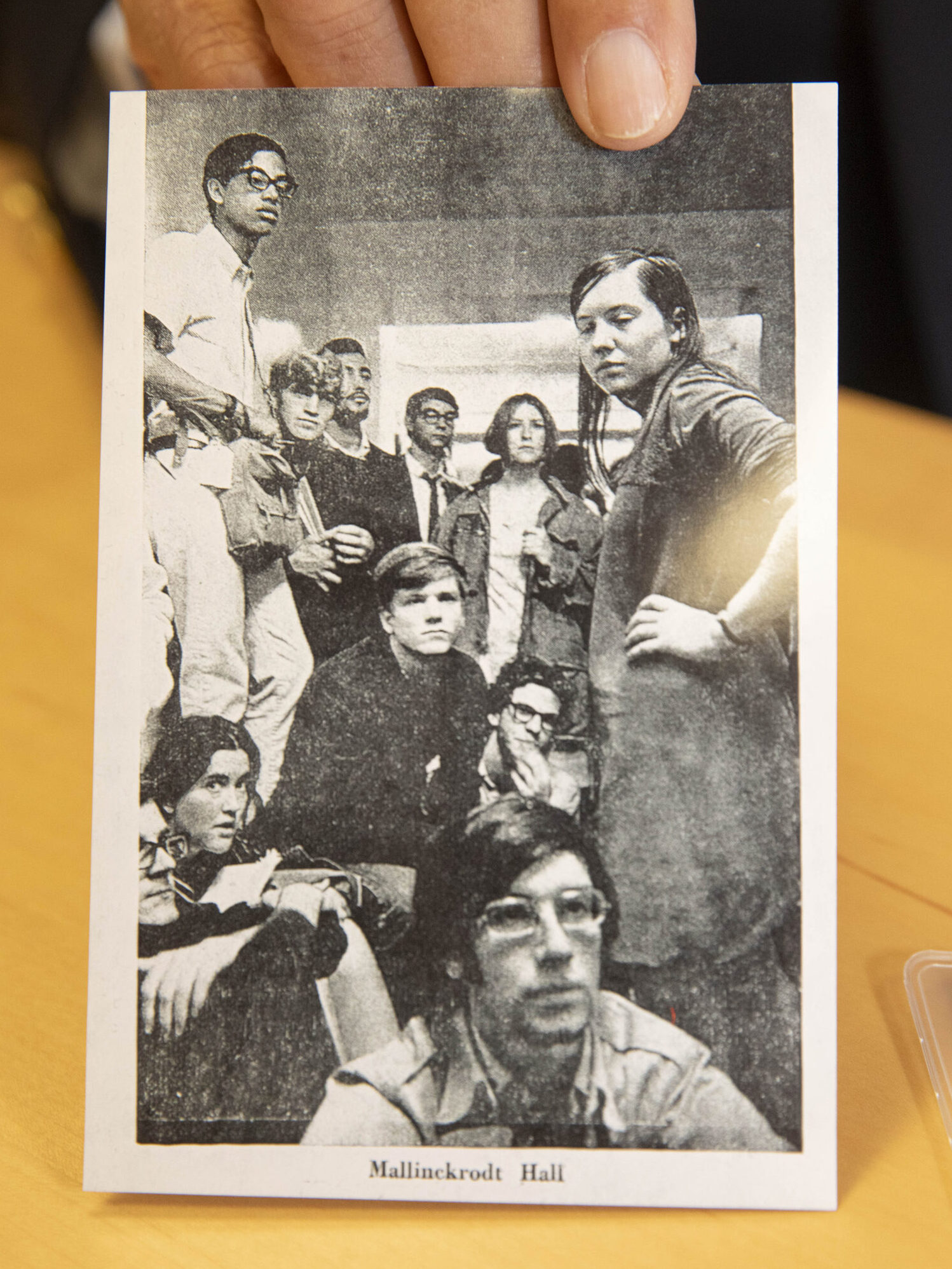

He also captured images of significant happenings on campus, including events like a student protest against Dow Chemical, the manufacturer of napalm, and a takeover of University Hall in April 1969.

But there are also quieter moments on campus and in the wider community. The collection includes images of young people taking part in smoke-ins and be-ins on the Boston and Cambridge commons, and shots of daily life on campus. Smith said that he particularly sought candid photos of African American students.

“There are a lot of pictures of Black students on the white campus in context, not just in protest,” he said.

It turned out that Smith’s goals dovetailed with those of major groups like the National Urban League, which hired him to be part of its Southern Education Reporting Service.

“These were national organizations that were sort of behind the scenes, promoting or encouraging more Black entry into colleges. And there was funding to do a recruiting brochure, if you will,” Smith said.

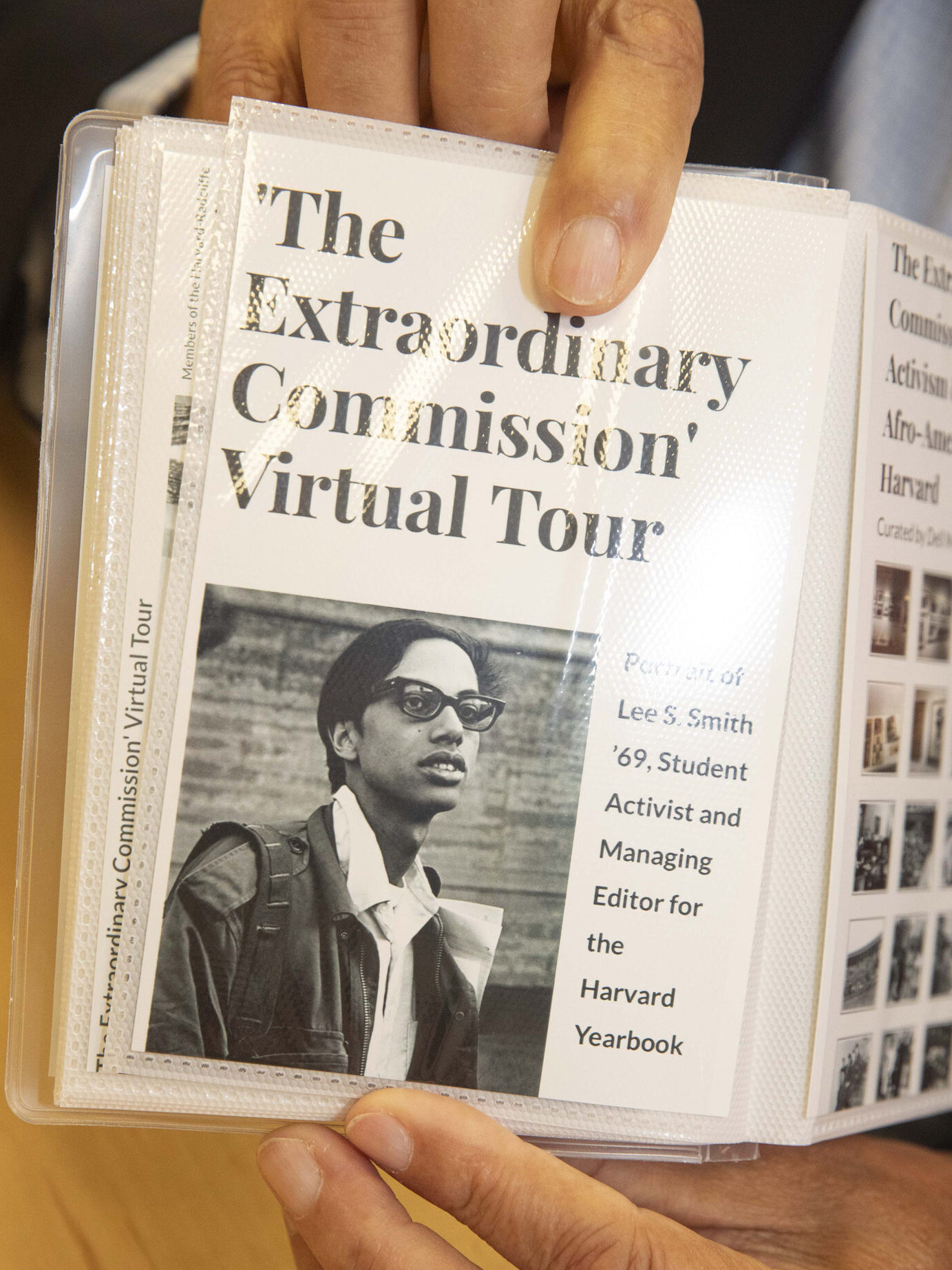

Together he and classmate Charles Hamilton created two publications — “The Black Student on the White Campus” and “College and the Black Student.”

Distributed nationally, with one such publication underwritten by Time magazine, the pair traveled to Harvard, Cornell, Boston University, Yale, Mount Holyoke, and other colleges.

Smith eventually made history as the first Black managing editor of the yearbook. His senior year, 1969, the yearbook devoted 24 pages to essays and photos capturing the Black community on campus.

After College, Smith put away his camera and became a lawyer, working for the government and in higher education. He still had his negatives but viewed them as nothing more than a memento for himself and perhaps his old yearbook friends at their next reunion.

Decades later he was approached by Hutchins Center curator Dell Hamilton. In 2020 Smith’s photos were featured as part the 50th anniversary celebrations for the Department of African and African-American Studies, titled “The Extraordinary Commission: Student Activism and the Birth of Afro-American Studies at Harvard.”

That event stirred a memory for Smith. In the late 1980s, he was working on a project that required him to comb through national and state archives while researching a case that would lead to Prairie View A&M University, one of the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), securing a long overdue share of Texas’ higher education endowment fund.

“Well, having worked with some of the archivists and kinds of things that they had, what had dawned on me is that a lot of this stuff I have, particularly by Blacks at Harvard, it didn’t get into any publications,” Smith said.

It turned out the University Archives were very interested, and now anticipate the digitization and deposit of this collection to be completed by April 2024, just in time for next year’s yearbook anniversary.

“Anniversaries are wonderful opportunities to open doors and connect us with the Harvard community to bring in collections that reflect the student experience and the diversity of our community,” Kuipers said. “We’d love to hear from other alumni.”