Marcyliena H. Morgan (right), founding director Hiphop Archive & Research Institute, with her husband, Lawrence D. Bobo, dean of social science and the W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Social Sciences.

Photos by Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

How hip-hop got to Harvard

Colleagues, artists, friends gather to celebrate Marcyliena Morgan, founding director of University’s Archive & Research Institute

For three days, Tsai Auditorium had the feel of a giant dinner party.

Dozens of colleagues, collaborators, artists, family, and friends gathered there last month for a symposium celebrating linguistic anthropologist Marcyliena H. Morgan, founding director of the trailblazing Hiphop Archive & Research Institute at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research. The Ernest E. Monrad Professor of the Social Sciences and professor of African and African American Studies recently announced her transition to emerita status after more than 20 years as a faculty member.

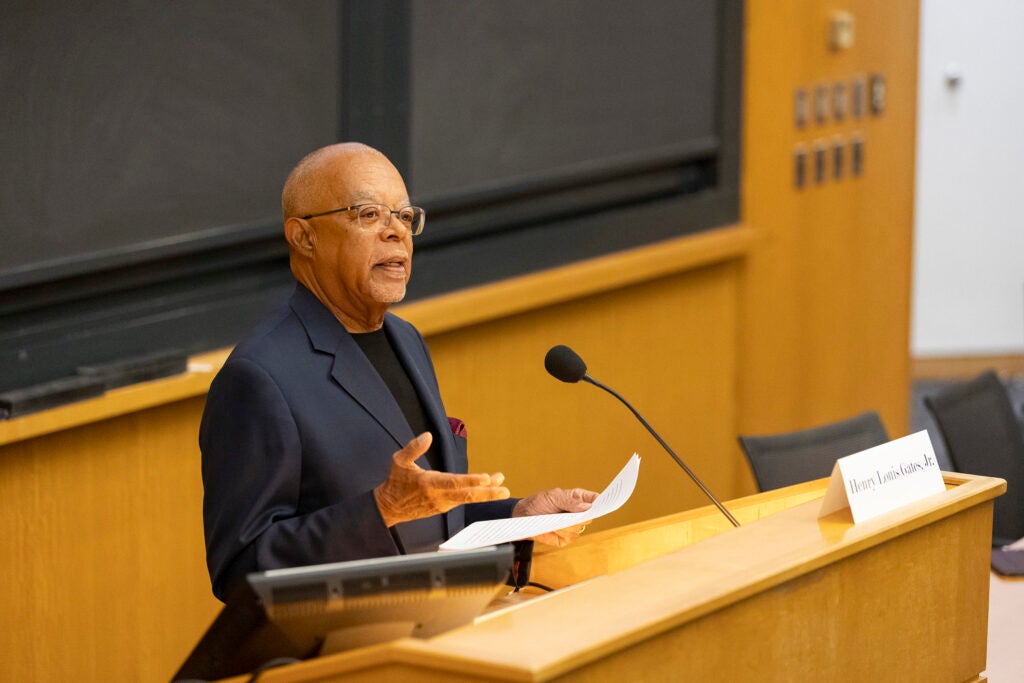

Calling Morgan the “scholar queen of hip-hop,” Hutchins Center Director Henry Louis Gates Jr. presented her with an architectural model of the archive’s sleek, gallery-like space, completed in 2002. It was also announced that a plaque honoring Morgan would be installed near the entrance in 2024.

Gates, a self-described “Motown man,” remembered Morgan first pitching him on the Hiphop Archive around 1996. The Alphonse Fletcher University Professor confessed to dismissing the genre as a passing fad. But Morgan proved persistent, he recalled.

‘‘‘This music,’ she said looking at me like I was an idiot, ‘was our youth vernacular language, manifesting itself in a completely new form of music, not only from coast to coast of the United States but spreading all around the world.’” It was “the lingua franca of American popular culture,” she told him, and it was here to stay.

Tracks by Queen Latifah, A Tribe Called Quest, and Lauryn Hill kept heads bobbing as guests arrived for the December symposium. In a year in which hip-hop turned 50, Morgan’s big idea appeared all the more prescient. Gates and others opted for the stronger term of “genius” in characterizing her vision for legitimizing hip-hop as a subject worthy of the academy. Today, Cornell University houses a similar archive, with regional collections situated at UMass Boston, Georgia State University, and the College of William & Mary.

More than 30 speakers took the podium over three days, including Abel Valenzuela Jr., the interim dean of UCLA’s Division of Social Sciences, who spoke on Morgan’s lasting impact on that campus, where she started collecting albums, magazines, and concert posters as a linguistics professor in the 1990s. Taking it all in with Morgan from the front row was Lawrence D. Bobo, her husband of 25 years as well as the dean of social science and the W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Social Sciences.

Most early hip-hop scholars explored the music’s cultural impact through the lens of political science or sociology, explained Morgan’s former student Brandon M. Terry ’05, now the John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Social Sciences and co-director of the Hutchins Center’s Institute on Policing, Incarceration, & Public Safety. But Morgan, who has written extensively on the topic, including “The Real Hiphop: Battling for Knowledge, Power, and Respect in the LA Underground” (2009), focused more on artistic elements including “the innovative uses of language and intertextuality and voice performance,” Terry said.

Calling Marcyliena Morgan the “scholar queen of hip-hop,” Hutchins Center Director Henry Louis Gates Jr. remembered her first pitching him on the Hiphop Archive around 1996.

Harvard University

Terry discussed the Hiphop Archive’s Classic Crates project, a collection of seminal hip-hop albums that will be housed in the Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library, the University’s primary music repository, alongside works by Mozart, Beethoven, and Chopin. Morgan commissions liner-note essays to explicate the intellectual and aesthetic achievements of every selection.

Terry took a moment to read from his Classic Crates analysis of the patrimonial themes in “To Pimp a Butterfly,” a chart-topping, critically acclaimed 2015 album by Kendrick Lamar, who became the first rap artist to win a Pulitzer Prize in music for “Damn.” in 2018. “Butterfly” features the artist “coming to terms with the meaning of his hometown, Compton, Calif., the infamous epicenter of West Coast gangsta rap, and its iconic antiheroes” from the group N.W.A., he said.

“I was thinking as Brandon was talking … I actually can’t imagine Kendrick Lamar having received a Pulitzer without the imprimatur of the archive,” offered Imani Perry, J.D. ’00, Ph.D. ’00, the 2023 MacArthur Fellow who recently joined the Harvard faculty as Henry A. Morss Jr. and Elisabeth W. Morss Professor of Studies of Women, Gender and Sexuality and of African and African American Studies.

Morgan worked to increase the archive’s influence and visibility by convening panels and roundtables over the decades, including a 2003 discussion on the cultural contributions of rapper Tupac Shakur. Women, queer, and nontraditional scholars were invited to these sessions long before it was standard practice, Perry said. That level of inclusion advanced scholarship on Black popular culture, simply because it broadened the base of top hip-hop thinkers.

The symposium struck an intimate, even familial tone given the presence of Morgan’s nieces, cousins, and younger sister. Many reminisced about visiting Morgan and Bobo’s Cambridge home, only to be floored by her exceptional fried chicken or coconut cake. Duke University African and African American Studies Professor Mark Anthony Neal invoked the metaphor of “Marcy’s table” in describing Morgan’s capacity to nurture and unite.

In a final panel, a group of former students and collaborators described Morgan’s personal impact. “There are people of color all over this planet who have Ph.D.s because Marcyliena Morgan mentored us and believed in us,” said anthropologist Dionne M. Bennett, an assistant professor in the African American Studies Department at City University of New York and an associate with the Hiphop Archive since 2002.

Michael Davis, M.A. ’22, an animator, designer, and graphic novelist who has worked at Harvard University for more than 10 years, started collaborating with Morgan on the archive’s creative branding in 2015. He spoke movingly of retreating to the space when needing a break from real-world pressures. “I would come to the archive as a sanctuary,” he shared. “I would have a moment to breathe and reconnect not just with friends and colleagues, but with the culture that I love — the culture I feel I am from.