Photos by Stephanie Mitchell, Kris Snibbe, Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographers

How they found the work they were ‘meant’ to do

Faculty share the class, mentor, book, experience that changed everything and set them on path to scholarly calling

If you’re lucky, your career path will lead to a calling that combines both skills and passion. But finding the right track isn’t always easy without guidance or inspiration — from a role model, mentor, class, life experience, or even an inspiring book. We asked several faculty members what influences pointed them to their fields of study. Answers were edited for clarity and length.

From West Point to Harvard (via Potok, Freud, and rats)

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Joseph P. Gone ’92, Ph.D., Professor of Anthropology and of Global Health and Social Medicine; Faculty Director, Harvard University Native American Program

During an undergraduate holiday break, I returned home to Kalispell, Montana, for a brief respite from the rigors of cadet life at the U.S. Military Academy. West Point was the epitome of a mind-numbing, pre-professional education, though my psychology courses had been captivating. In Kalispell, I plucked a book off the shelf at our public library: Chaim Potok’s “The Chosen” (1967). This novel features a friendship between two Jewish youths in New York, one the son of an ultra-orthodox Hasidic rabbi. This son, Danny Saunders, was expected to one day assume his father’s role in the community’s religious dynasty, but instead he secretly fell in love with the works of Sigmund Freud. Later, in college, he studied psychology, only to learn that running rats through mazes was the trend; Freud was unwelcome in the curriculum. In that moment, I had an epiphany: Psychology is a capacious field, inclusive of theoretical questions about human nature, scientific questions about laws of behavior, and applied questions about helping others in distress. In short, psychologists could practice both psychoanalysis and rat-running. Not long thereafter, I transferred to Harvard College to study psychology.

In demography course, ‘everything clicked’

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Marcia Castro, Andelot Professor of Demography, Global Health and Population, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

When I was in my first year of high school in my native Brazil, I took a class that covered regional problems, and I loved it. It dealt with migration, aging, mortality, and even though it was about the study of populations, I had no idea that was demography. The word demography never came up in the class, but I loved the instructor and the subject matter. I went to college to study statistics, and I did an internship at a governmental agency in Brazil’s Social Security Ministry. While I was an intern, demographer Maria Helena Henriques came to give a short course on demography. And then everything clicked for me. I remembered my high school class, and I realized I had a passion for demography. Maria Helena Henriques inspired me to pursue a master’s in Brazil, where I found two superb mentors to whom I am forever grateful: Diana Sawyer and José Alberto Carvalho. I applied to Princeton to do a Ph.D. in demography, and professors Burt Singer and Noreen Goldman became my mentors and role models. My high school teacher, Fernando, and Maria Helena gave me the spark to become a demographer, and my mentors during my master’s and Ph.D. helped me connect the dots and inspired me to be where I am now. At Princeton, I decided to focus on health because that’s what I’m passionate about. That’s when I started studying malaria and expanded to other diseases.

It does make a difference to have a good mentor; that kind of relationship makes a huge difference in somebody’s career, especially if you want to go to academia. My advice is to find someone whose work you are passionate about, and make sure that that person is willing to invest in you. Finding a good mentor is not a matter of luck; it’s a huge investment on both sides.

Building on mother’s service to students

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Tracey Hucks, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Africana Religious Studies, Harvard Divinity School; Suzanne Young Murray Professor (Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study)

Becoming an educator was inspired by my mother, Doretha Leary Hucks, and was the continuation of her dream. She worked in the library reading lab in a New York City Public School helping young African American and Latinx youth to improve upon their reading skills. She enrolled in night school determined to acquire certification and to lead her own classroom. This goal was short-lived when she and the other women she worked with in the reading lab successively succumbed to radical forms of cancer.

My mother died in 1984 at the age of 48. The Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act was passed in 1986. I was a sophomore in college at the time of her death and upon graduation, chartered a path to the Ph.D. In truth, I am a willing surrogate and proxy, standing in for my mother and for her early dream of being in academic service to students. She inspired me to help others fall in love with the gift of learning; to care for the whole person; and to reach beyond your circumstances. I am honored to have fulfilled her dream while embracing and living it as my own.

Still captivated by ‘mystery’ of physics

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Giulia Semeghini, Assistant Professor of Applied Physics Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

The major influence in my career path as a physicist was a scientific exhibit I attended when I was in high school. I was generally good in math and sciences in high school but wasn’t really interested in physics until that moment. The exhibit was mainly about physics, and the speaker was passionate about it; he was the person that made me see what physics is about; a field that allows you to look deeper into what happens around us and understand why things behave the way they do.

In college, the professor who taught me quantum physics inspired me to study this field. I remember the first class; I was fascinated by what he was telling us, and by this field that was completely new to me. I felt enthralled, and again a key part of this was the professor’s enthusiasm and curiosity. The way he was explaining quantum physics was as if he was revealing a mystery, and that feeling of awe remains in me even after many years. During my Ph.D. and first postdoc at the University of Florence, I had two advisers who had a huge influence on me. They helped me see what it means to ask the right questions and find creative ways to seek the answers. They also helped me understand my talents and value my contribution to research.

Sometimes the way teachers teach physics in high school is a little bit dry and not very interesting. It’s about learning formulas. To students who may have an intuition that physics might be something of interest for them, I’d say that they should try to explore it outside school and try to meet people that practice physics.

Book ‘radically changed’ approach to education

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

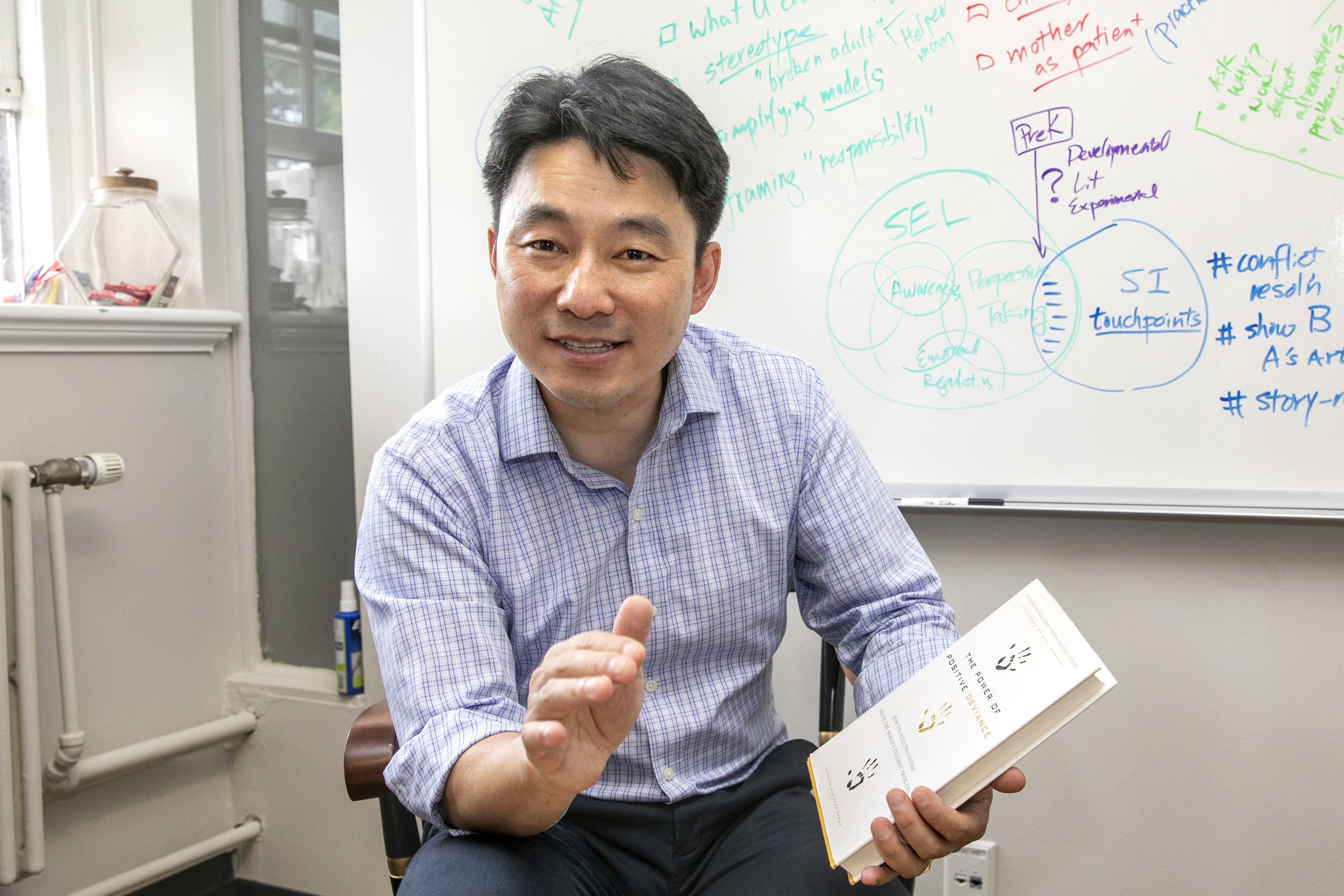

Junlei Li, Saul Zaentz Senior Lecturer in Early Childhood Education; Faculty Co-Chair, Human Development and Education Program, Harvard Graduate School of Education

I was trained, like most Ph.D.’s in my profession, to find and fix what is wrong in the fields of human development and education. My work in early childhood started in orphanages — the culmination of “what went wrong” from society to community to family. “The Power of Positive Deviance,” a book that was influential in my career path, takes a very different approach. It is about having the kind of respect and trust for communities to discover what is going well even in the most difficult contexts. It radically changed how I approach my field — it taught me to honor the expertise and wisdom of those who are already on the front lines of any difficult work. It led me to learn from villagers who fostered children with severe disabilities, childcare providers in low-income communities, and social workers in youth group homes. Eventually, I sat down with one of the co-authors — Monique Sternin, a graduate of our Graduate School of Education — at Harvard Square and thanked her for all that she did and shared in that book.