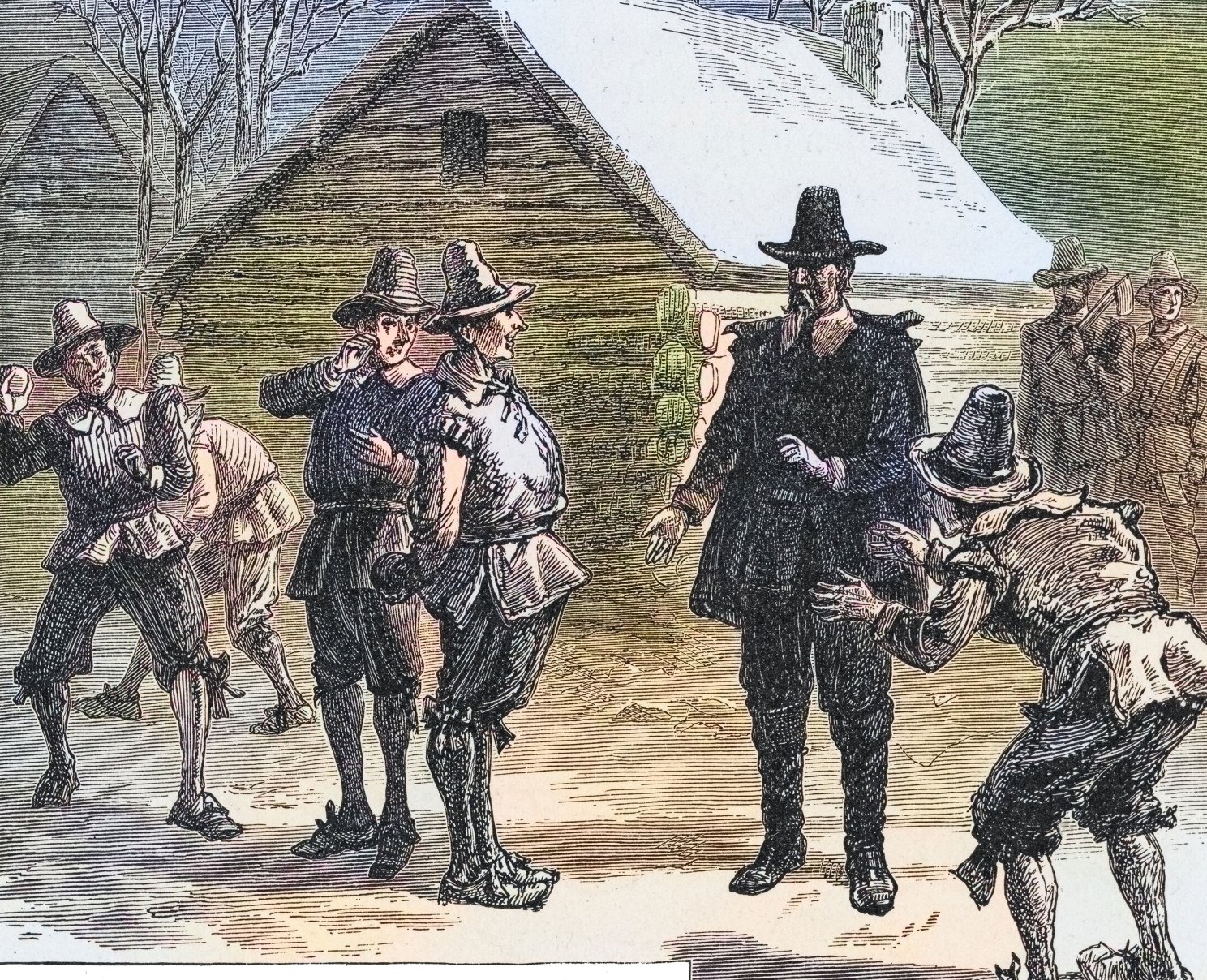

Engraving of the Plymouth Colony governor confiscating toys from Pilgrims on Christmas Day.

Getty Images

On the first day of Christmas … we partied like it was 1499

Church historian traces celebration’s path from wild revelry through Puritan’s progress to Hallmark holiday

On the first day of Christmas there was drunken carousing, gambling, street fights, bizarre costumes, and lots of sex. And it went on like that for at least 11 more days.

What sounds more like Carnival in New Orleans or a lost weekend in Las Vegas was, in fact, how Christmas was celebrated in England from the late Middle Ages into the early 17th century.

For the English Protestants who left in the early 1600s for Plymouth seeking religious freedom, such Bacchanalian festivities to mark the birth of Christ were utterly scandalous. And so true to the city’s “banned in Boston” reputation, the Puritans renounced English traditions and declared Dec. 25 a workday, even going so far as to criminalize Christmas from 1659 to 1681.

One prominent Boston minister, Increase Mather, a 1659 Harvard College graduate who served as its president from 1681-1701, led the opposition, railing in his writings against Christmas celebrants “consumed in Compotations, in Interludes, in playing at Cards, in Revellings, in excess of Wine, in mad Mirth.”

The Gazette spoke with David F. Holland, John A. Bartlett Professor of New England Church History and interim dean of Harvard Divinity School, about this early war on Christmas and how we ended up with the Hallmark holiday season of today. Interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

David F. Holland

GAZETTE: Christmas was a very bawdy, unruly affair in 17th-century England and Europe when Protestant pilgrims were setting sail for Plymouth colony and Massachusetts. How was it celebrated?

HOLLAND: Christmas lands at the end of the harvest season and before the heart of the winter. And so, it was often seen as the moment when people had a chance to really feast.

It was very difficult to get fresh meat except in that period when the animals were slaughtered prior to the winter. Most of the work of the harvest had been done, so there was this window in the season when there was an opportunity to really let loose, to take time away from the daily drudgery, to indulge in foods that would not have been available most of the rest of the year.

European life was generally characterized by scarcity, and so, this moment of abundance presented a kind of celebratory possibility that, in many ways, just happened to coincide with longstanding tradition about the birth of Jesus Christ.

The form that Christmas observance or what they called “keeping Christmas” would have taken was often almost riotous behavior — a lot of drinking, a lot of gathering in large crowds.

One of the distinctive features of a traditional English Christmas was very conspicuous begging or asking for food by people lower on the social ladder toward people who were better positioned, including something that might look a little bit like Halloween. You’d knock on a door, you would demand food or drink, usually alcoholic drink. If the host did not provide what you had asked for then there was a cultural expectation that you would cause some mischief for the host.

Sometimes this spiraled out of control into actual moments of violence or conflict. Christmas became associated with sexual licentiousness, the loosening of normal social mores.

“Christmas lands at the end of the harvest season and before the heart of the winter. And so, it was often seen as the moment when people had a chance to really feast.”

GAZETTE: Many traditions we associate with the Christmas holidays were, in fact, drawn from cultures across Northern Europe, from ancient Rome, and from paganism, like exchanging gifts, giving tips to workers, and the Christmas tree.

HOLLAND: A holly wreath would also be exemplary of that. … Many of those symbols of life and renewal predate Christianity itself. That’s part of the complaint that Puritans had, that these are pre-Christian observances not warranted by the Bible.

Puritans abided by something known as the regulative principle, which was that you couldn’t worship in a way that was not explicitly prescribed in scripture. Anything else was seen as a kind of pollution of pure worship and that includes things like the singing of hymns and carols. They would have sung the text of scripture in the form of the Psalms, but little more, and certainly not Christmas carols.

Anything associated with Christian worship that was seen as a cultural inheritance rather than revealed in scripture would have been considered a kind of corruption of Christian purity and something they felt obliged to oppose, like a Christmas tree, a wreath, a yule log. The ritualistic lighting of candles would be another example.

GAZETTE: Did the Church of England or the Catholic Church condone this merrymaking or did they turn a blind eye to it?

HOLLAND: A little bit of both. I think there was a recognition among some that the pressures of the social order were so great for most of the rest of the year that the social harmony was maintained by having a kind of release and that the effort to suppress that too aggressively would, in fact, be destabilizing to the social order.

This is the principle of Carnival — that the inversion of social ordering on a day or two a year actually reinforced the preservation of that social order the rest of the year. There certainly would have been people who made the case for not trying to suppress it too much because that would agitate the lower classes and create more problems than it was worth.

You do have critics who say, “It’s gone too far, you’re profaning the name of Christ in your observance of Christmas.” There certainly was a discourse like that.

One of the arguments made among English Protestants is that the celebration of Christmas is too Catholic, that a Protestant should move toward a more scripturally based Christian observance, and that Catholicism was too deeply rooted in its relationship with paganism. Therefore, it was seen to be an expression of English Protestantism to distance oneself a little bit from these modes of observing Christmas.

But it was always complicated: different groups observing in different ways with different levels of critique from those who found their observance offensive.

There would have been relatively little success in suppressing it until the Puritans came to power in the mid-1600s. In England, there was never really an official effort to deny people the opportunity to observe Christmas in this way except during the period when Puritans controlled the government in the aftermath of the English Civil War.

Photo by Justin Knight

Justin Knight

GAZETTE: From 1621, a year after the Pilgrims landed in Plymouth, these raucous Christmas celebrations appalled the Puritans living in Massachusetts. Some years later the Rev. Increase Mather still railed about these unholy celebrations in his sermons, calling them “highly dishonorable to the name of Christ.” Was this view widely held or confined largely to clergy and elites?

HOLLAND: It was quite well agreed upon. The early Puritan migration to New England was quite socially homogenous. It’s a very middle-class movement — and by design. Cultures of servitude and slavery were a part of the colonial experience, so I don’t want to overstate this, but you did not have the kind of class structure that one would have found in England at the time.

The early Puritan settlers didn’t want to bring the truly indigent with them from England. Nor did you have an aristocratic class. So, many of the early Puritan migrants represented a shared social position as well as a common religious commitment.

Certainly, you did have people in early New England who resisted the suppression of Christmas. Sailors and fishermen were often seen as the source of social unrest or resistance to observing Puritan mores in coastal towns like Marblehead, where they were somewhat beyond the reach of the Puritan power structure. So, it wasn’t entirely uniform.

One of the earliest accounts is Gov. William Bradford in Plymouth colony running around on that first Christmas trying to get people to stop having a good time, suggesting that some folks were ready to party.

One of the big objections was that it was a disruption to Puritan thrift and industry. The idea that you would keep working through Christmas was part of that Puritan ethos. So independent of the riotous revelry, or the Catholic pagan elements, it’s just a question of good hard work that gets disrupted by Christmas.

That first Christmas in Plymouth demonstrates both the commitment to resisting a culture of Christmas and the fact that the denial of Christmas was not universally observed. That persists up until the mid-1700s.

The Massachusetts General Court actually outlawed Christmas. It became a criminal offense in 1659 through 1681 to observe Christmas. The fact that they felt that had to pass a law suggests a concern that some people were trying to keep Christmas, but also that there was widespread support for its suppression.

GAZETTE: Was some of this objection driven by a desire to separate culturally from England and to establish a belief system here that was apart from the Church of England?

HOLLAND: During the early generations of Puritan settlement, the goal was to set an example for England. These people were deeply English. This is truer of the Puritans in Massachusetts than of the Pilgrims in Plymouth, who were more committed to a concept of separatism.

The goal was to demonstrate what a godly community could look like and how God would bless and benefit that community. To be this shining example so that people in England would say, “Ah, that’s what we can become. If we do the same thing, we will receive similar kinds of divine blessings and we’ll prosper accordingly.”

The goal was to restore and purify England, not necessarily to reject it. And so, by resisting something like the culture of Christmas, they’re trying to set an example of what English society could look like if it were properly committed to true Christian principle.

“The Massachusetts General Court actually outlawed Christmas. It became a criminal offense in 1659 through 1681 to observe Christmas.”

GAZETTE: By the mid-1800s, the Christmas Resistance, as it were, had largely faded. What happened?

HOLLAND: The Puritan governance of New England had waned. By the early 1700s, you do have more religious diversity. You also get a form of Christmas emerging that is less Elizabethan riotousness and more reverent, more sedate.

And so, as Christmas itself transforms into a more socially respectable, more religiously acceptable form, and as society itself diversifies and liberalizes away from those early Puritan commitments, it creates this convergence of forces that allow for a gradual introduction of Christmas observance into the regular cadence of New England life.

Even then, up through the end of the 1700s and into the early 1800s, it’s a very modest affair, something that looks more like Thanksgiving than a modern Christmas, with a little extra food and families gathering.

We start to see people writing music specifically for Christmas in the last couple of decades of the 1700s; calendars and almanacs begin to consistently designate Christmas Day. So, these cultural markers show us that it is getting more and more acceptable, and that the practice looks more and more familiar to us as something other than Carnival.

And so, by the early 1800s, it’s a part of their sense of the season, but still not commercialized, not really the modern Christmas in the sense of nuclear family gathering in private in the morning and exchanging gifts. That’s still a way off. But it’s no longer this object of opposition that it had been 100 years earlier.