iStock by Getty Images

The eye as we’ve never seen it

Researchers’ atlas pinpoints where disease-causing genes are expressed, raising hope for inroads against blindness

Glaucoma and macular degeneration cause blindness in millions of people every year. Hundreds of genes have been implicated for increasing susceptibility to the diseases, and such genes are often starting points for therapies that prevent or reverse blindness. But it’s not always clear where, when, and why these genes are expressed across the visual system.

In a culmination of more than a decade of research, Harvard scientists have completed a detailed analysis that could not only light the way to better, more targeted gene therapies for blindness, but also inspire a new appreciation for the vast complexity of human vision. The team, led by neurobiologist Joshua Sanes, has authored a complete catalog of the nearly 160 cell types found across all the structures of the human eye, as well as an inventory of the genes each cell type expresses. They detail their findings, which they call a cell atlas of the human eye, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Our atlas can be used to assess which cell types express any disease-associated gene, thereby suggesting ways to design effective therapeutic strategies,” Sanes said.

The Jeff C. Tarr Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and founding director of Harvard’s Center for Brain Science, Sanes has long been interested in how complex neural circuits form in the mammalian brain, particularly in the neural retina, which lines the back of the eye and acts as part camera, part graphics processor. Most irreversible blindness results from retinal disease. The retina is also a relatively easy part of the brain to study because it’s outside the skull, “which means you can study it without drilling any holes,” he said.

More than 10 years ago, Sanes and colleagues started using single-cell RNA sequencing to identify genes expressed across thousands of retinal cells at once. The then-new technology, alongside increasingly powerful bioinformatics, allowed them to catalog neural retina cells by their RNA transcripts, which are bits of unique information that become readable when DNA is being copied into RNA in each cell.

Intrigued by the pathogenesis of blindness, Sanes turned to using RNA sequencing for analyzing not just the cells of the retina, but of the entire human eye, including surrounding structures like the cornea, iris, and optic nerve. Many of these structures have been implicated in loss of vision.

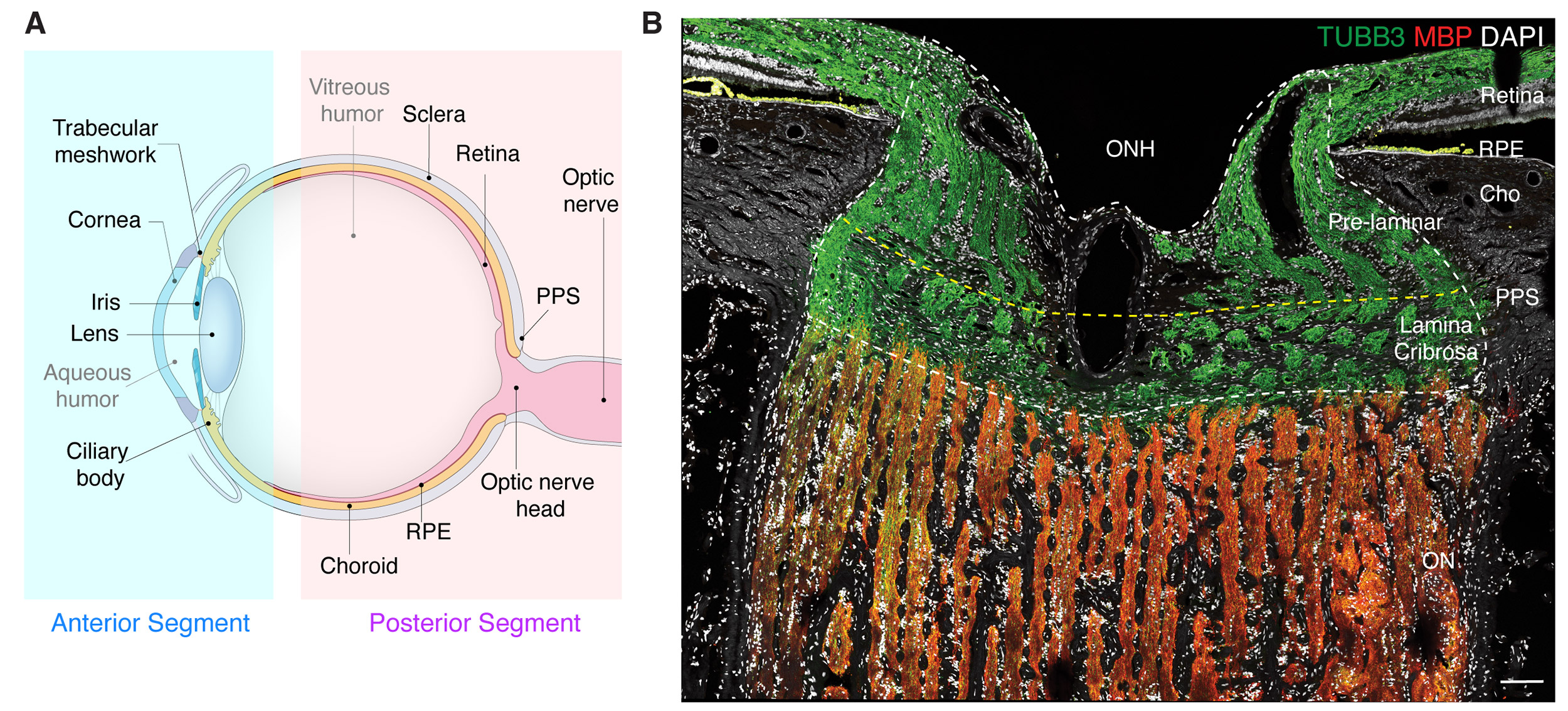

(A) Diagram of the human eye and the optic nerve. (B) Section of the optic nerve head and surrounding tissues immunostained to show different cell types.

Courtesy of Sanes Lab

For the new study, the team analyzed 151,000 single cells, including the optic nerve, optic nerve head, sclera, and retinal pigment epithelium.

Altogether, they have identified nearly 160 types of cells. Some are specific to structures like the lens or retina, while others are shared by multiple structures. Their analysis forms a blueprint for knowing which cell types are expressing what genes, and crucially, where the genes are being expressed.

As a proof point, they used their atlas to map the expression of more than 180 genes associated with glaucoma, which is the leading cause of blindness worldwide. Glaucoma involves not just the retina, but also ocular tissues in both the front and back of the eye. The researchers found glaucoma-associated genes expressed across numerous cell types, including in the retina, trabecular meshwork, and optic nerve head, as well as some places they didn’t expect, like the retinal pigment epithelium.

Mapping genetic expression across the human eye may inform blindness therapeutics while also offering clues to the evolution of human vision. To this end, Sanes’ lab has also used single-RNA sequencing to create neural cell atlases of primates, rodents, fish, birds, and other animal species. By comparing what cell types are shared across species, the researchers can make inferences about how evolution has acted preferentially to shape different retinal designs.

Funding for this work included support from the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative and the National Institutes of Health.