Who deserves a liver transplant?

With deaths from alcohol-related disease on rise, some in the field are rethinking criteria that exclude patients from life-saving care

During one of his first rotations as a medical student, John Messinger had a patient in his 40s with alcohol-related hepatitis. Because the patient had been treated for alcohol use disorder and relapsed, he was ineligible for a liver transplant. Messinger watched the patient deteriorate, knowing more could have been done to save his life.

Current guidelines determining who can get a transplant are tied to longstanding ethical debates driven by the scarcity of donor livers — as of January, more than 10,000 patients were on the wait list. But alcohol-related liver disease has recently become the lead indication for a transplant, and studies show it’s only gotten deadlier since the pandemic, especially for young adults. In light of this, some in the field are re-evaluating eligibility requirements that penalize patients who struggle with addiction, especially those who are Black or low-income.

Messinger, a student at Harvard Medical School, spoke with the Gazette about his recent paper on improving equity in liver transplants and where he sees opportunities for change. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q&A

John Messinger

GAZETTE: Alcohol-related liver disease is the leading indication for liver transplant in the U.S. How does that compare to other indicators?

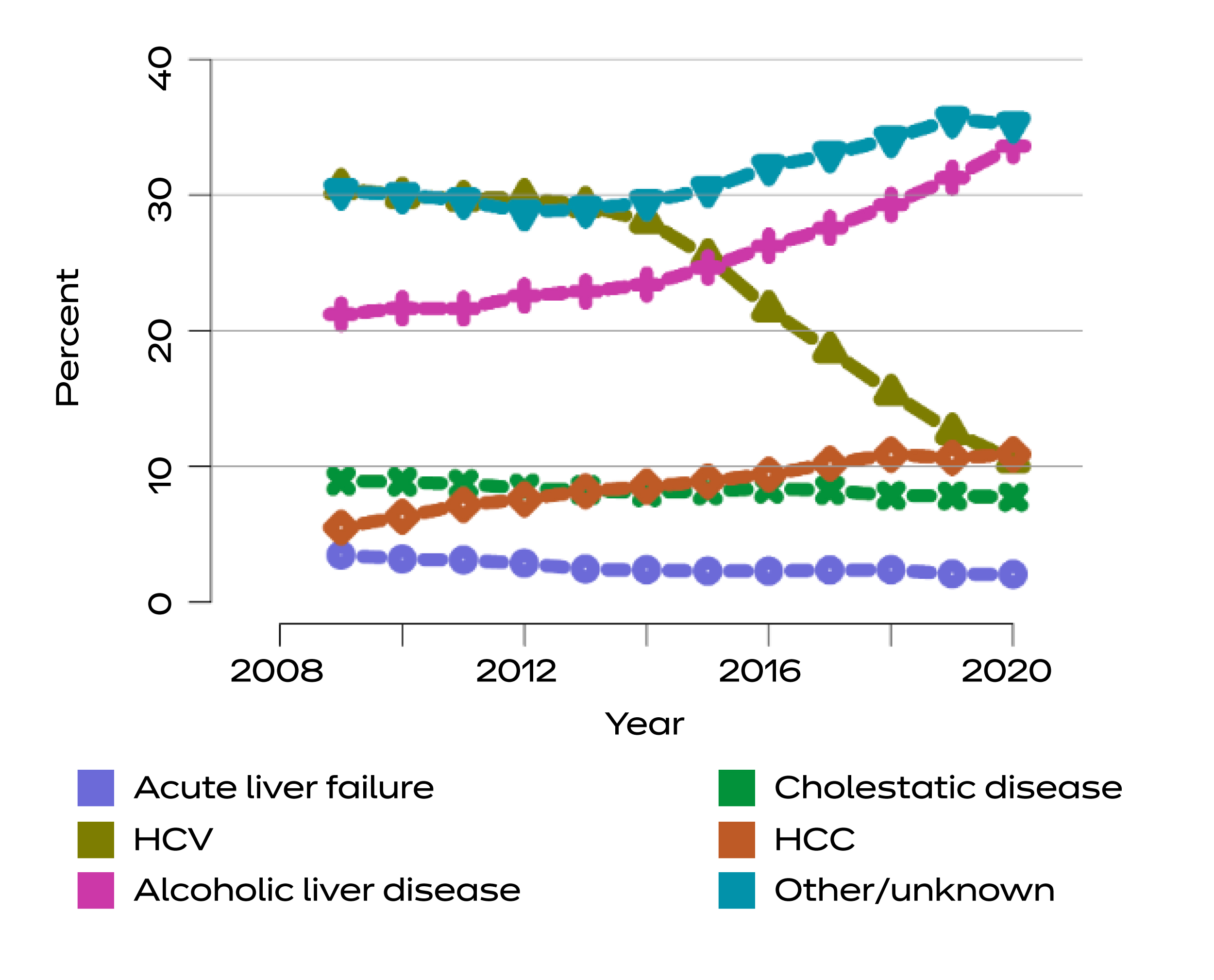

MESSINGER: This trend only recently changed. Around the mid-2010s, the leading indication for liver transplant was hepatitis C, which is a virus that often results in chronic infection that, over time, leads to liver failure. For a long time, there was no reliable way to prevent that. Around 2010, there was a new medication that came out for hepatitis C that effectively cured patients. This led to a whole population of people who were being transplanted to dwindle.

But during that time, we’ve also seen rapidly rising rates of severe alcohol use that can lead to liver failure. In 2020, over 30 percent of patients listed for transplants had alcohol-related liver disease, more than any other single diagnosis. There are also other types of liver disease that are on the rise, like nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which is related to obesity, diabetes, and/or metabolic syndrome. Those indicators might overtake alcohol-related liver disease in the future.

Distribution of adults waiting for liver transplant by diagnosis.

Source: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

GAZETTE: Because of the demographic of people who need liver transplants, there’s been an ongoing ethical debate regarding who should be eligible for a transplant. Could you talk more about that?

MESSINGER: The challenge for transplant providers is that they want to make sure that they’re being good stewards of a scarce resource. That starts to get into questions like, who’s deserving? But at the root of that is providers wanting to choose who they think has the best chance of success. They don’t want somebody receiving a liver to have a high risk of getting worse, whether it be through continued alcohol use or relapse that can lead to recurrent liver failure.

There is a lot of stigma surrounding alcohol use and addiction in general, and that means that people assume that people with alcohol-related liver disease don’t have much hope of success following transplant, that they will relapse and fail. That was the old way of thinking, which has continued to evolve. We can do better to treat alcohol-related liver disease. It would open the door for more patients to be considered “deserving,” good candidates for liver transplants.

GAZETTE: Does research show that patients who struggle with alcohol use are more likely to see negative outcomes?

MESSINGER: In the very earliest data around alcohol-related liver disease, it did show worse outcomes for those patients. But at the time, there weren’t great treatments for alcohol use disorder. So there are presumptions made now about the outcomes for these patients based on a set of circumstances that have since changed. More recently, the data show patients with alcohol-related liver disease have outcomes that are comparable, if not better, than other types of liver disease, even for certain populations who traditionally weren’t even considered for transplant.

GAZETTE: In what ways does the current system fail patients?

MESSINGER: An important distinction in alcohol-related liver diseases is that there are two types: alcohol-related cirrhosis (a gradual scarring and fibrosis that occurs over time) and alcohol-related hepatitis (very acute inflammation). With hepatitis, it can lead to acute liver failure and high rates of mortality within six months of diagnosis. In the current system, there have been mandatory abstinence periods, which means patients may have to prove six months of abstinence before even being considered. For those patients, they don’t even make it on the list and are dying at very high rates.

“There are a lot of patients who would have a good outcome that we’re automatically excluding from consideration.”

Photo courtesy of John Messinger

Newer studies have shown that for early liver transplant, even patients without mandatory abstinence periods can go on to do very well. That’s the real tension we’re trying to get at: There will be patients with alcohol and liver disease who have poor outcomes, so how do we pick the candidates who are the most likely to do the best? We need to change how we’re making that calculus, because there are a lot of patients who would have a good outcome that we’re automatically excluding from consideration. If we don’t create nuance for patients, we exclude a lot of people who should be worth considering.

GAZETTE: What are some of the ways you suggest changing the process?

MESSINGER: Two ways: one is the evaluation process that determines who’s getting a liver transplant; the other is better treating patients so we can maximize their outcomes.

One of the first things we can do is make sure we’re not using arbitrary criteria that sound like they make sense, but aren’t as good at predicting outcomes. One example of this is social support. There’s a lot of discussion about social support in the transplant world, saying that because it’s a very arduous treatment process, people need family members to be able to be there for them, to transport them to and from all these appointments, make sure that they are getting the care that they need. But studies don’t show a clear relationship between social support and outcomes. And in fact, people who are from higher socioeconomic status are better able to demonstrate social support, leading to inequity in who is chosen. People from more disadvantaged backgrounds might be excluded from transplant if they can’t show they have social support, even though there isn’t great evidence to show that it’s a good reason to exclude them.

There’s also racial inequity that exists within the system. Multiple studies show that Black individuals are less likely to be listed for transplant than their white or non-white counterparts. This goes back to the type of criteria we use, one being criminal legal involvement. We know that Black communities are disproportionately policed and might be more likely to be arrested and have a criminal legal history than their white counterparts. So we need to think really carefully about how those criteria disadvantage certain populations.

GAZETTE: And what about improving treatment, such as addressing the underlying issue of alcohol use disorder?

MESSINGER: We talk about a few recommendations in the paper, but one is integrating specialty addiction treatment into transplant centers so that every patient has some type of specialty addiction care. Transplant providers themselves should have some basic understanding of addiction and treatment. Studies show many providers don’t have the confidence to prescribe medications for alcohol use disorder — or other treatments that are really standard of care for those patients.

We should also be using what’s known as harm-reduction principles. In the world of addiction, harm reduction has been used widely. This is the idea that drug use is a natural part of life, and instead of trying to avoid or ignore that, we should instead think about the negative consequences of alcohol or drug use and try to address those. We know that as many as 20 percent or more of our patients will eventually relapse, despite all our efforts to select only the patients who do the best. So for those patients who do relapse, we want to be open and honest with them. Creating more realistic expectations — always with the goal of abstinence but acknowledging that sometimes relapses occur — would help improve the outcomes for these patients.

Because this isn’t routinely practiced, it is hard to imagine exactly what this would look like. This may mean offering patients placement in a residential treatment facility, increasing their frequency of outpatient visits with addiction specialists, or simply increasing the frequency of visits with the transplant provider to offer more support. However, we would need more research to understand what is the best way to intervene and help these patients.

GAZETTE: What are some of the challenges you see in trying to initiate these changes?

MESSINGER: It’s very hard for transplant providers to go out of their comfort zone. The accreditation of transplant centers is directly linked to patient outcomes. And that means that providers have to select patients who they know will do well, because not only is that individual liver on the line, but their ability to transplant more patients and stay accredited as a transplant center is on the line.

I am encouraged by the type of gradual change we’ve seen in liver transplant over the years. Three decades ago, there were statements by the [National Institutes of Health] saying that almost nobody should be considered for transplant if they have alcohol use disorder, where now it’s the No. 1 indication for a transplant. But there’s still a lot of barriers to making the types of changes that are important to ensure equity for this population.