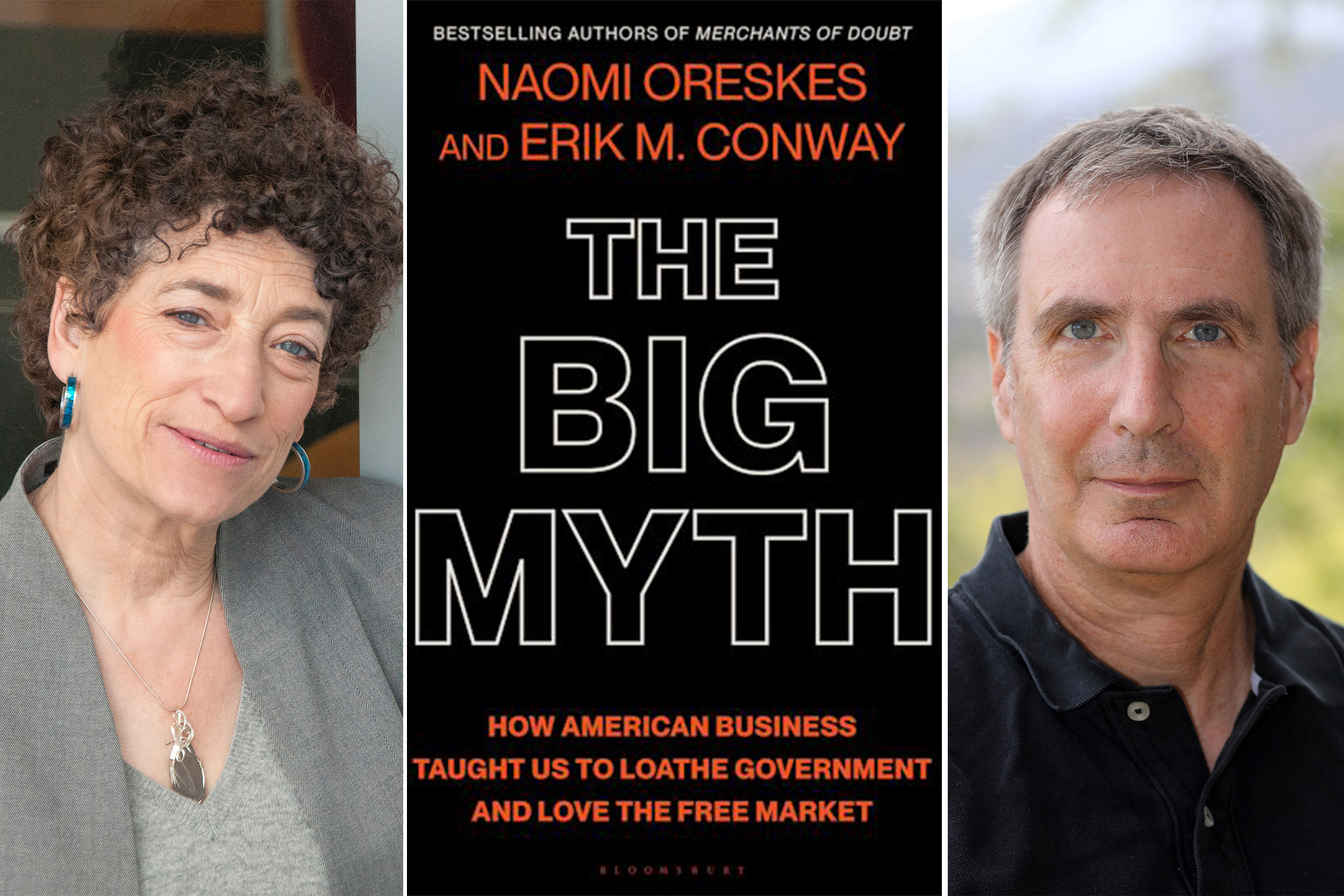

Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway.

Photos by Silvia Mazzocchin and Andrea Donnellay

How did Americans come to trust markets more than government?

New book by Naomi Oreskes, Erik Conway traces history of Big Business campaign to push ‘big myth’

Excerpted from “The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market” by Naomi Oreskes, Henry Charles Lea Professor of the History of Science, and Erik M. Conway, published Bloomsbury Publishing.

This is the story of how American business manufactured a myth that has, for decades and to our detriment, held us in its grip. It is the true history of a false idea: the idea of “the magic of the marketplace.”

Some people call it market absolutism or market essentialism. In the 1990s, George Soros popularized the name we find most apt: market fundamentalism. It’s a quasi-religious belief that the best way to address our needs — whether economic or otherwise — is to let markets do their thing, and not rely on government. Market fundamentalists treat “The Market” as a proper noun: something unique and unto itself, that has agency and even wisdom, that functions best when left unfettered and unregulated, undisturbed and unperturbed. Government, according to the myth, cannot improve the functioning of markets; it can only interfere. Governments therefore need to stay out of the way, lest they “distort” the market and prevent it from doing its “magic.” In the late 20th century, market fundamentalism was cloaked in the seemingly ancient raiments of received wisdom. In fact, it was more or less invented in the 20th century.

Classical liberal economists — including Adam Smith — recognized that government served essential functions, including building infrastructure for everyone’s benefit and regulating banks, which, left to their own devices, could destroy an economy. They also recognized that taxation was required to enable governments to perform those functions. But in the early 20th century, a group of self-styled “neo-liberals” shifted economic and political thinking radically. They argued that any government action in the marketplace, even well intentioned, compromised the freedom of individuals to do as they pleased — and therefore put us on the road to totalitarianism. Political and economic freedom were “indivisible,” they insisted: any compromise to the latter was a threat to the former — any compromise at all, even to address obvious ills like child labor or workplace injury. Why did we ever come to accept a worldview so impervious to facts? A worldview Smith himself, often thought of as the father of free-market capitalism, would have rejected? How did so many Americans come to have so much faith in markets and so little faith in government?

Market fundamentalism is not just the belief that free markets are the best means to run an economic system but also the belief that they are the only means that will not ultimately destroy our other freedoms. It is the belief in the primacy of economic freedom not just to generate wealth but as a bulwark of political freedom. And it is the belief that markets exist outside of politics and culture, so that it can be logical to speak of leaving them “alone.”

We are all familiar with the idea that, as Soros has summarized, “the doctrine of laissez-faire capitalism holds that the common good is best served by the uninhibited pursuit of self-interest.” That’s the core argument Adam Smith made in 1776 and contented capitalists have accepted ever since. Market fundamentalists, however, depart from Smith by insisting there is no “common good,” merely the sum of all the individual private goods. For this reason, they reject government’s claims to represent “the people”: there are only people — individuals — who represent themselves, and they do this most effectively not through their governments, even democratically elected ones, but through free choices in free markets.

Milton Friedman, America’s most famous market fundamentalist, went so far as to argue that voting was not democratic, because it could too easily be distorted by special interests and because in any case most voters were ignorant. But rather than consider how special interests might be mitigated or how voters could be better informed, he maintained that true freedom was not expressed in the voting booth. “The economic market provides a greater degree of freedom than the political market,” Friedman said in South Africa in 1976, as he encouraged the citizens of that country not to fuss over apartheid, but to preserve and expand their market-based economy.

Friedman’s argument works when we are talking about the freedom to buy, say, shoes of any type. But it fails when we consider the larger picture, including deceptive advertising, aggressive and misleading PR campaigns, and what economists call “external costs”: costs that are invisible to or misunderstood by the shoe buyers, or that accrue to people who didn’t buy those shoes at all. Pollution is an external cost. What happens when the shoe manufacturer dumps toxic chemicals behind the plant and hides that fact from its workers, investors, and customers? Friedman downplayed the problem by giving it the friendly label of “neighborhood effects,” and claimed that any remedy would almost always be worse than the disease, because of the loss of freedoms or compromises to property rights typically associated with government regulations. In some cases, he may have been right. Regulations do compromise someone’s freedom in order to protect the freedom (and welfare) of others. When it comes to pollution, the “freedom” of factories to dump toxic wastes has been rightly rejected. When it comes to climate change, the “freedom” of corporations to sell oil, gas, and coal jeopardizes the rest of us. This creates a fundamental dilemma for the fundamentalists. But rather than rethink their arguments, market fundamentalists protect their worldview by denying that climate change is real or asserting that somehow “The Market” will fix it, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Friedman held that capitalism and freedom are two indivisible sides of the same coin, but this “indivisibility thesis” predates him by decades. In the early 20th century, it was promoted in the United States by a group of industrialists working under the umbrella of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). NAM and its allies used the thesis to argue against political reforms that today we take for granted, such as laws limiting child labor, establishing workers’ compensation, and creating the federal income tax. In the 1930s, they aligned themselves with the electricity industry and used the thesis to argue against the Rural Electrification Administration, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and other elements of the New Deal. Mostly they lost these fights, in part because the thesis suffered a fatal flaw: it wasn’t true. Electricity was a case in point. Markets had failed to bring electricity to millions of Americans who wanted it, but the government had succeeded, and rural Americans were better off economically and no less free. Indeed, they were arguably freer than before, because they now had electrical appliances that reduced manual labor and electric lights to lengthen the usable day.

Because the indivisibility thesis had so little foundation in fact, American business leaders needed to find other ways to shore it up. One way was propaganda. In the 1920s, the National Electric Light Association (NELA) launched a massive campaign that included, among other things, the hiring of academics to rewrite textbooks and develop curricula to promote pro- market, antigovernment perspectives in emerging business schools and economics programs across the country. They also recruited experts to “prove” that private electricity was cheaper than public electricity, even when the available facts showed otherwise. In the 1930s, NAM reprised the effort, with a multimillion-dollar propaganda campaign to convince Americans that business and industry were working just fine, and that the real causes of the Great Depression were unionized labor’s unreasonable demands, coupled with the government’s excessive interference in business affairs and federal taxation that starved industry of the monies it needed to expand productive capacity. Well into the 1940s, NAM produced books, pamphlets, radio programs, lecture series, and documentary and feature films (and later television programs) designed to influence what newspapers had to say about the economy and American life, what teachers taught in the classroom, and, above all, what the American people believed.

Another strategy was to recruit sympathetic intellectuals to help give the myth credibility. For this, American businessmen relied on imports: the economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek, leaders of the Austrian school of economics. In the 1940s, a group linked to NAM paid for Mises and Hayek to come to America, arranged for them to be hired at New York University and the University of Chicago, respectively, and worked assiduously to promote the economists’ ideas, both in business circles and among the American people generally. This included publishing a dumbed-down version of Hayek’s famous book “The Road to Serfdom” in Reader’s Digest and a cartoon version of it in Look magazine. In the 1950s, Ronald Reagan would encounter that Reader’s Digest version; decades later “The Road to Serfdom” would be promoted by right-wing radio hosts Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh and touted by influential Republicans including Senator Ted Cruz and House leader Paul Ryan.

Businessmen helped create America’s first libertarian think tank, the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE), established in 1946 by Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce manager Leonard Read to peddle pro-market, antigovernment ideology. They also funded the Hayek-aligned Mont Pelerin Society, a cadre of mostly European economists, cultural commentators, and political theorists promoting a renewed commitment to free-market principles under the aegis of what became known as neoliberalism. And they would help Milton Friedman write his most influential book, “Capitalism and Freedom” — essentially a restatement of the indivisibility thesis — which would dramatically reshape the American cultural conversation in the 1970s and ’80s. In 1988, Reagan would award Friedman both the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the National Medal of Science.

Few of Friedman’s readers knew that the book’s success was not the product of open competition in the marketplace of ideas: “Capitalism and Freedom” had been financed and nurtured by American businessmen, and it was the most public part of a much larger project. Reader’s Digest notwithstanding, the people who had brought Hayek to America had quickly concluded that his approach was too intellectual and too European to break through to the public.

Most Americans know that before becoming a politician Reagan was an actor, but fewer are aware that Reagan’s flagging screen career was revived by a job with the General Electric Corporation (GE). Reagan hosted the popular television show “General Electric Theater,” where each week his voice and face reached into tens of millions of homes, promoting didactic stories of individualism and free enterprise. At the same time, he traveled across the country on behalf of GE — visiting factories, making speeches at schools, and doing the dinner circuit in communities where GE had a presence — promoting the corporation’s stridently individualist antiunion and antigovernment vision.

Reagan’s mentor in this work was GE executive Lemuel Ricketts Boulware, whose antiunion tactics were so extreme they earned a name: Boulwarism. (They would also earn GE several indictments for federal labor law violations.) And while Reagan helped GE promote the ideology of free markets and free choice, the company conspired to rig electricity markets (an offense for which it would be successfully prosecuted in the 1960s). Boulware’s influence transformed Reagan’s politics. He went into GE a New Deal Democrat and came out an antigovernment conservative Republican. GE transformed Reagan’s political fortunes as well; he emerged from his time there with powerful backers in corporate America who helped him launch his career in elected office.

Reagan was known as the Great Communicator, and the success of American market fundamentalism was ultimately a triumph of public relations: its advocates built a myth and persuaded Americans of its truth. By the 1970s, what had begun as a self-interested defense of business prerogatives — one that was factually dubious and characteristically supported by gross distortions and misrepresentations of history — had been transmogrified into a seemingly intellectually robust body of thought. Meanwhile, a network of libertarian think tanks, heavily funded by industries selling dangerous products including tobacco and fossil fuels, had been established to promote these views in schools, in universities, and in American life writ large. Among other things, these think tanks distributed free of charge millions of copies of Hayek’s and Friedman’s (and Ayn Rand’s) books. Meanwhile, progressive foundations mostly focused on specific issues — like saving whales or expanding access to education — not realizing that a larger ideological battle was under way. The myth spread, influencing American presidents from Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan to Bill Clinton and Barack Obama and, most recently, Donald Trump.

Americans in the early 20th century were largely suspicious of “Big Business” and saw the government as their ally. By the later decades of the century, this had flipped: many Americans now admired business leaders as “entrepreneurs” and “job creators” and believed it made more sense to count on the “magic of the marketplace” to solve problems than to engage government. Many Americans saw government as dead weight, taxation as unfair or even a form of theft. That they accepted these claims is proof of this story’s importance: propaganda and persuasion had worked. The people involved in this project were intellectually diverse and geographically dispersed, but they were also in important (and sometimes startling) ways interconnected. Theirs was not a conspiracy, but it was a network of people who knew each other, supported each other morally and financially, and used this mutual support to promote a singular myth.

Copyright © 2023 by Naomi Oreskes & Erik M. Conway. All rights reserved.