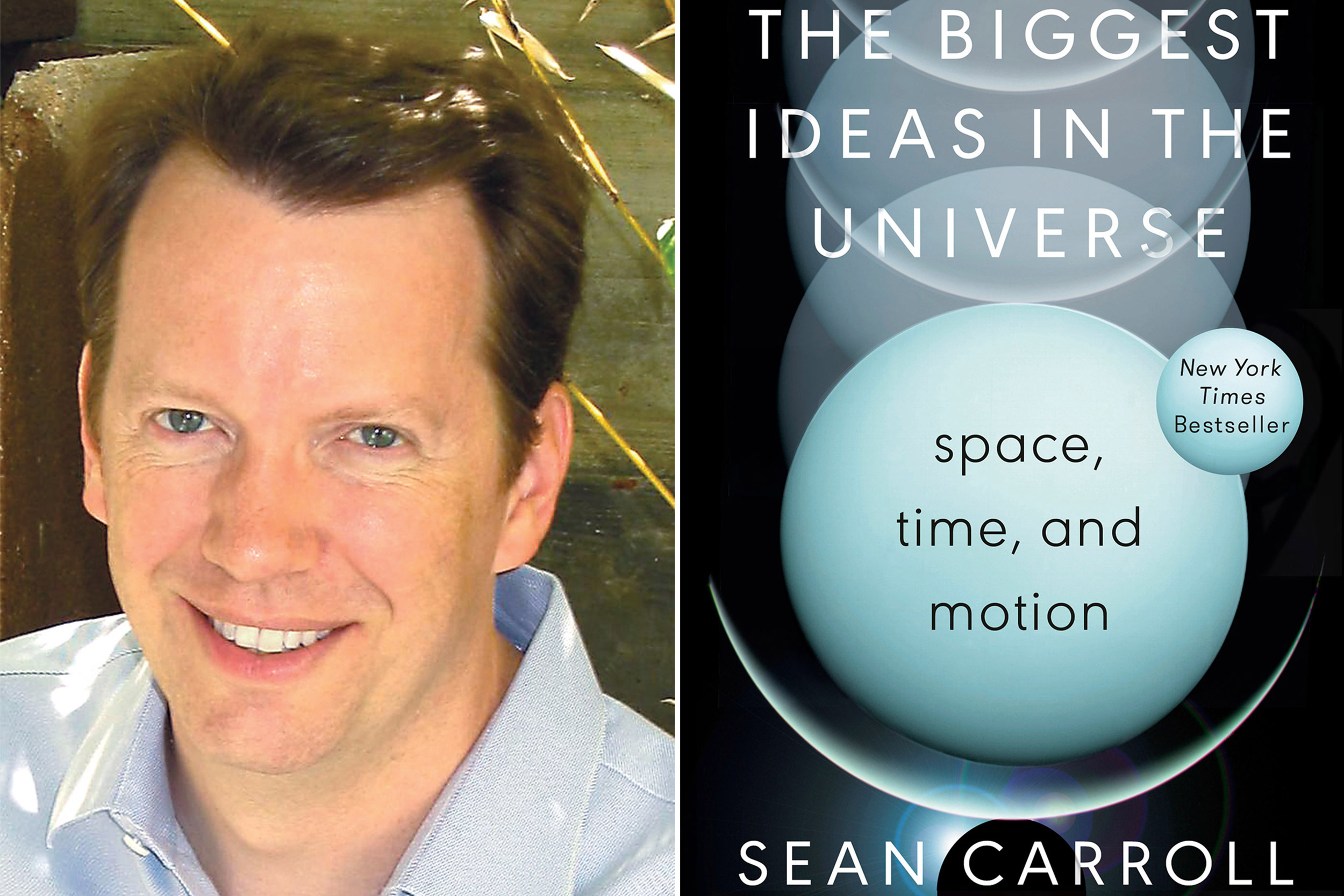

Photo by Jennifer Ouellette

His dream? To see two pub regulars arguing over existence of infinity in nature

Sean Carroll turning his pandemic video mash-ups of popular science romp, college-level physics textbooks into books

Editor’s note: This story has been corrected to reflect that Sean Carroll will speak Friday at the Science Center, Hall B.

Sean Carroll bought a green screen and a camera during the first pandemic lockdowns of early 2020. Each week, the theoretical physicist and acclaimed science writer shot two hour-long videos explaining fundamental ideas in modern physics, including conservation, quantum mechanics, gravity, and black holes.

Carroll is turning that series, “The Biggest Ideas in the Universe,” into a namesake book trilogy. On Friday he will give an in-person talk at the Science Center, Hall B, about volume one, “The Biggest Ideas in the Universe: Space, Time, and Motion.” Both video and book series are conceived as mash-ups of popular science romp and college-level textbook and aimed at an oft-neglected reader: one not so interested they’d want a degree but enough to crave a detailed grasp of how it all really works.

“Secretly, the real audience for this book is my 16-year-old self. I would have loved to have this,” said Carroll, who received his Ph.D. in astronomy from Harvard in 1993. Today, he is the Homewood Professor of Natural Philosophy at Johns Hopkins University. The Gazette spoke with Carroll about his project and why he dreams of a world where people can debate their favorite dark-matter candidates — and other physics mysteries — at a local pub.

Q&A

Sean Carroll

GAZETTE: You said you started your video series to help keep people connected during the surreal early days of the pandemic. Did it accomplish what you hoped?

CARROLL: Yes, they kept people connected, and the pandemic was a great pleasure. No, I was definitely a little bit less ambitious than that. Maybe it did more good for me than for the rest of the world. But the reception was pretty good. The most popular video has something like 800,000 views. And it’s an hour and a half of me writing down tensor equations for general relativity. It’s not the usual viral hit on YouTube.

GAZETTE: So then, why turn the videos into a book trilogy? Why aren’t the videos enough?

CARROLL: Like I said, 800,000 people watched the most popular video. Let me tell you, it’s not 800,000 people who are buying the book. But that doesn’t mean that the people who do buy the book, even though it’s a smaller number, have watched the videos. Some people just like reading books. And honestly, you can learn more from the books because it’s a slower process.

GAZETTE: It also seems like you’ve invented a whole new genre, something between a popular science book and a textbook. Was that intentional?

CARROLL: That was absolutely intentional. I’ve written a few popular books. But for the most part, my goal is not just to be pedagogical. My books make an argument that you can disagree with, whether it’s about the nature of reality or the interpretation of quantum mechanics. Whereas these books try very hard to stick to things that everyone agrees with. There’s a vast audience in between the ones who read popular books and the ones who read textbooks. That’s a gap I’m happy to try to fill.

“Science is not just a set of final answers; it’s a way of thinking about the world and learning new things.”

GAZETTE: Throughout the book, you present a lot of abstract concepts, like infinity, that are challenging for most people to conceptualize, even if they’re important to questions about our natural world. Why are these concepts still valuable to explore?

CARROLL I’m not just trying to explain the bare bones of the physics. I brought in little historical stories, philosophical background, mathematical niceties, and so forth. In the back of my mind, I’m always thinking like, “What is it that got me really interested?” With infinity, we use it in the continuum and our best descriptions of the natural world without really being sure whether it’s necessary. But I honestly don’t know whether we’re on the right track. So, even though I tried to stick with things that everyone agrees on, I’m happy to point out places where we don’t agree.

GAZETTE: Are there any physics concepts that are commonly misunderstood?

CARROLL: Oh, my goodness, there are so many. Within the scope of this book, I talked about space and time and space time. Classical mechanics up through general relativity. There are obviously a lot of misimpressions about general relativity, curved space time, the expanding universe, and things like that. But I don’t dwell on that. The tiny bit I’ve learned from academic research into misinformation and learning is that if you try to teach something by saying, “Here’s the wrong thing that you might think is true. And now I’m going to fix it,” people end up thinking the wrong thing because you put the idea in their heads. I try to spend most of my time thinking about the correct conceptions.

GAZETTE: For this first book, you travel all the way from Aristotle and Newton to modern research on black holes. What’s next?

CARROLL: I’m working on book two as we speak, and that’s all about quantum mechanics and quantum field theory. The third book will be complexity and emergence. Some of that is just a rubric that covers thermodynamics and cosmology, but the ideas of complex systems, criticality, and networks are hugely important to identify the ways in which the microscopic rules of the universe build up together to make this crazy complex macroscopic world we live in.

GAZETTE: You’ve said you’d love to hear people discussing physics at the local pub or in line at the grocery store. Apart from making you and other theoretical physicists happy, what might that accomplish?

CARROLL: I’m not an expert on science education. But from what little I do understand, we focus way too much on a set of facts. Science is not just a set of final answers; it’s a way of thinking about the world and learning new things. So, if people understood how and why we got to specific ideas, they would, I think, have a better idea of how to keep uncertainty in mind, judge new evidence, think about the world in a quantitative way, and be open to changing their minds. All those things are crucially important to science and certainly serve people more broadly.

GAZETTE: Which physics topic would you be most excited to hear people chatting about at the pub?

CARROLL: The cheeky response would be Hamiltonian mechanics. In the book, we learn Newtonian mechanics, then a whole other way of doing it, called Hamiltonian mechanics, and then another way, Lagrangian mechanics. Three different ways to do the same underlying physics. Is one of them more right? We don’t know. But it’s important to conceptualize the same ideas from different angles because one might suggest a different way forward. We’re not done yet. We’re still thinking about what happens next. So, in this book, I’m trying to provide both the ideas that are going to be used for the next 500 years and what to look out for as we move forward.