“Across every dimension of well-being that we looked at — happiness, health, meaning, character, relationships, financial stability … those who are 18 to 25 felt they were worse off,” said Tyler VanderWeele about a new study he authored.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Why are young people so miserable?

They tally lowest life-satisfaction scores among all age groups of those 18 and older in Harvard-led study, reversal of results of past surveys

Twenty years ago, life satisfaction surveys of those 18 and older showed the highest readings among America’s younger and older adults, with those in between struggling with jobs, families, and other cares of middle life. Now, a Harvard-led study examining a dozen measures of well-being show younger adults tallying the lowest scores of any age group. Tyler VanderWeele, director of the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science and senior author of the study, said the results reflect not just a longer-standing mental health crisis among younger Americans that predates and was worsened by the pandemic, but a broader crisis in which they perceive not just their mental but also their physical health, social connectedness, and other measures of flourishing as worse than other age groups. VanderWeele, the John L. Loeb and Frances Lehman Loeb Professor of Epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said that should grab policymakers’ attention.

Q&A

Tyler VanderWeele

GAZETTE: Clearly, they’re related, but how is well-being different from mental health?

VANDERWEELE: Obviously, mental health is important. It is important to address issues of anxiety, depression, trauma, suicidality for youth and for adults. Having said that, I think we’ve neglected broader questions of well-being or flourishing that I understand in very holistic terms as living in a state in which all aspects of one’s life are good. That takes into account mental health, physical health, and — more broadly — happiness, having a sense of meaning and purpose, trying to be a good person, one’s social relationships, and the financial, material conditions that sustain these things that people care about.

GAZETTE: The report compares results of a survey earlier this year against a similar study in 2000. What did that survey show about our state of well-being 22 years ago?

VANDERWEELE: A number of studies had found those who were younger and those who were older — if you just looked at happiness and life satisfaction — tended to be doing better than those in the middle. The speculation was that those in midlife were struggling more, dealing with young children, maybe also aging parents. Maybe they were at a point in their careers where they were trying to get ahead, possibly even having a midlife crisis. For those who were younger, the statistics from past decades suggested they were happier, maybe with a sense of greater opportunity, fewer responsibilities, more opportunities for social connection.

What was perhaps surprising in earlier surveys was that those who were older were also doing better than those in middle age. Though health problems often emerge with age, people were still happier. Maybe they felt that the struggles of life were resolved, or they had more time to connect socially. There’s also some evidence of greater emotional regulation as one ages, greater gratitude for what has taken place. These are averages, obviously, that disguise a lot of variability, but this curve was fairly consistently observed across countries.

GAZETTE: What did you find in your most recent survey?

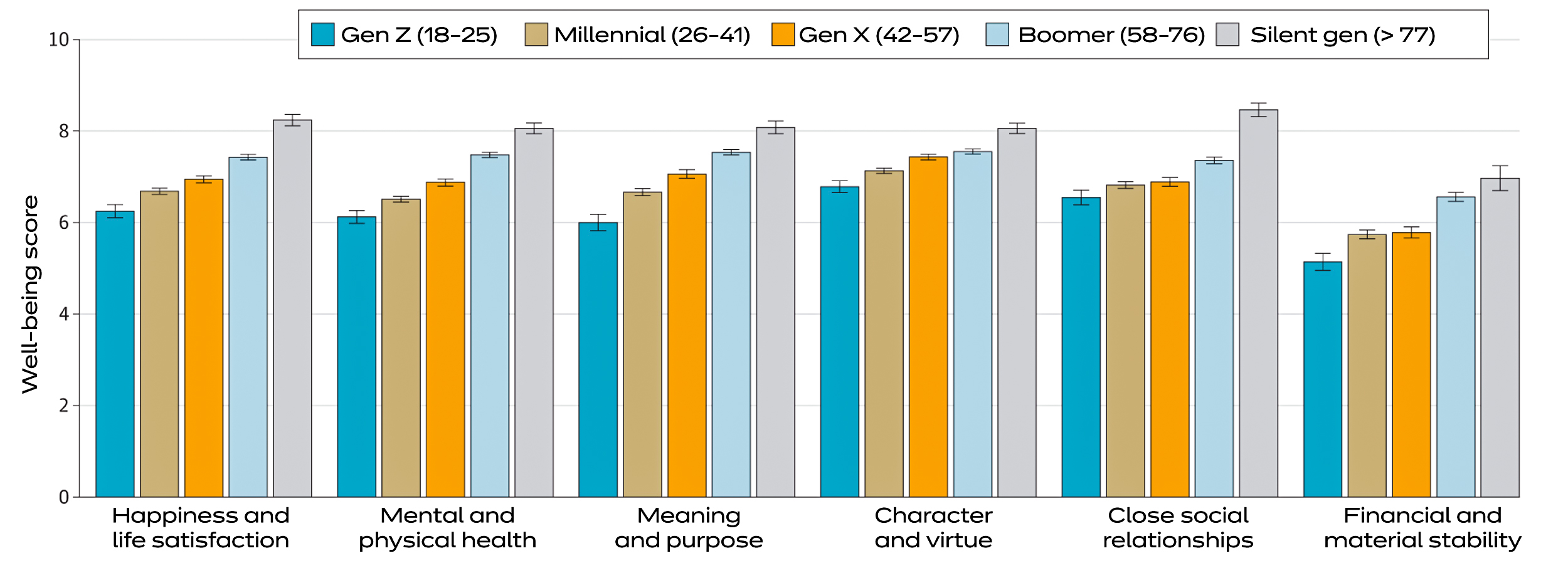

VANDERWEELE: We were beginning to see this in January 2020, right before the pandemic. But January 2022 was the first time it was just absolutely clear: across every dimension of well-being that we looked at — happiness, health, meaning, character, relationships, financial stability — each one was strictly increasing with age. Those who are 18 to 25 felt they were worse off across all these dimensions. It was pretty striking, pretty disturbing.

Source: “National Data on Age Gradients in Well-being Among US Adults”

GAZETTE: One thing that stood out to me was that it was true even for physical health. You’d think that would be a lay-up for young people. How do we explain that?

VANDERWEELE: It is powerful. Young people perceive themselves as not being physically healthy. One has to take into account the context of January 2022: We’re still in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic; Omicron has rendered social and communal interactions — once again — very difficult shortly after there was hope that things would be opening up. Some of this may thus be a sense of physical threat from the pandemic affecting young people more than others. Some of it may be a sense that they’re not engaging in the health behaviors that young people think they should be. Perhaps drug and alcohol use were up. It might be a discrepancy between experience and expectations. As a 24-year-old, perhaps here’s how I think I should feel physically, and I am just not there. So, all of those things likely come into play, but it is striking — shocking in some ways — that this group’s self-reported physical health was so low.

GAZETTE: Loneliness was another area called out in the study.

VANDERWEELE: Social connectedness was reported to be lowest in this group. Taking into account the timing, it’s probably not so surprising. There was prior evidence that young adults had been increasing in loneliness, and I think that was really accentuated by the pandemic. What we saw in the pandemic was that, on average, in the United States the sense of social connectedness went down a little bit, and loneliness went up a little bit, though not as much as one might have anticipated. Many people invested more in their families and their close friends, they connected via Zoom or other media with relatives. But the decline was substantial among young people. Those who are older had established relationships and established communities that they could draw upon, but young people at that stage in life are trying to build these relationships and trying to join these communities, and the opportunities to do so were so much more limited.

GAZETTE: Do we have any sense as to causes? Social media has been called out as a villain. The economy?

VANDERWEELE: The data we’re working with at present is purely descriptive. It doesn’t allow us to get at causes. But piecing together evidence from other studies, one can begin to understand what might be happening. Some of it is financial and economic. Job prospects for young people, in terms of the advancement that was foreseeable and anticipated 40 to 50 years ago, are just not there to the same degree. Debt from education has been weighing heavily on young people. Housing costs in cities are skyrocketing, while studies suggest that the majority of Gen Z wants to own a home but thinks it’s absolutely out of reach.

I think social media has contributed to declines in well-being. Past studies indicate that on average, the effects on well-being and mental health are negative, especially in those with high use. And high use is dramatically more common with young adults than others. Also, study after study — ours and others’ — have indicated that family life and participation in religious communities contribute across these aspects of flourishing. And participation in both of those are down substantially.

I think political polarization has had a role in this also. Many people feel: “How can I live in a country like this, where half the people are terrible?” Plus, the last five years have been a pretty turbulent time: the pandemic, Russia and Ukraine, concerns about climate change. We’re all confronting this, but older people have had longer periods of relative stability than those in their 20s. The world probably seems like a more threatening place.

GAZETTE: Are there any hints about a path ahead?

VANDERWEELE: Again, not from the survey responses itself, but perhaps from other studies that we and others have done. It’s pretty clear that these domains of well-being are interrelated. If you improve on social relationships, you’re also more likely to subsequently improve on happiness and health and to find meaning. If you have a sense of meaning, find new purpose, you’re likely to become happier and also have better health as well. So we need to work on each of these aspects: We need to promote relationships and communities; we need to address the financial conditions that young people are facing; we need to help them find systems of meaning. We do need to address mental health issues, questions of anxiety and depression, but just doing that isn’t going to be enough. The problem is much broader.

We also need to think about economic and health policy. To what extent are we thinking about the common good, not just across political lines but across generational lines? Not just what’s going to help us in the next three to five years, but that will shape future generations? We found larger differences across age groups than across groups defined by either gender or race. How can we structure society so that young people have opportunities, and so that their well-being is promoted? How do we get there from here? I don’t have all the answers, but it is a pretty important we take this seriously.