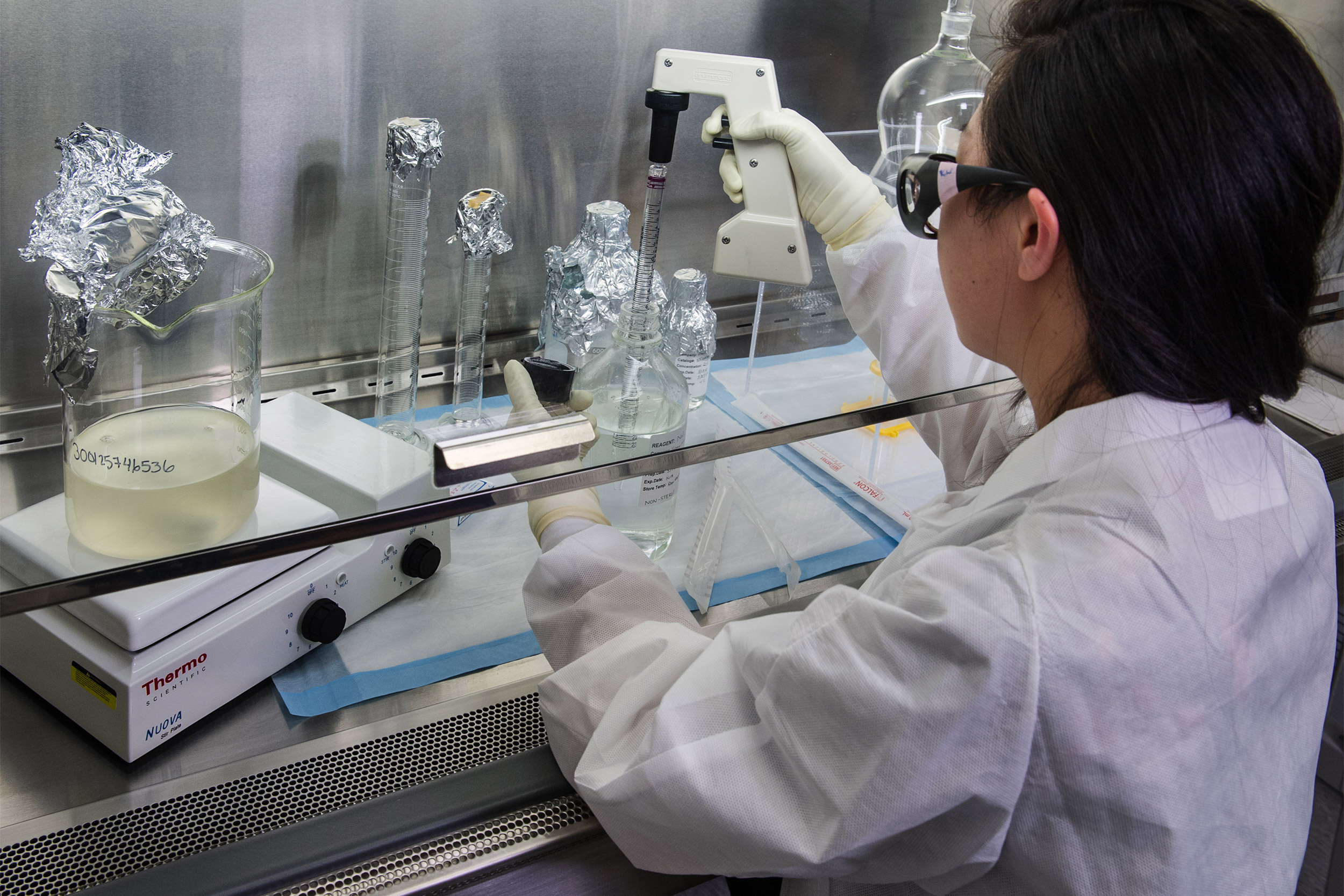

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention scientist is concentrating poliovirus from sewage. The virus was recently detected in New York wastewater.

James Gathany/CDC

Polio is back in the spotlight

An expert explains the two types and raises concerns over vaccine hesitancy

If you don’t know very much about polio, that’s understandable. Thanks to vaccination, there have been no cases of wild polio infection originating in the United States since 1979.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean that there isn’t any polio in the U.S. Travelers from other countries can bring it in — either the wild poliovirus, or the “vaccine-derived” virus. Recently, we have been hearing news about cases of polio, mostly vaccine-derived polio, and mostly originating from other countries, but wastewater data shows that poliovirus is spreading in some areas. Public health authorities report that an unvaccinated individual in New York was diagnosed with vaccine-derived poliovirus. Here’s what parents need to know.

What is vaccine-derived poliovirus?

The polio vaccine helps the body make the antibodies it needs to fight polio. The oral polio vaccine used in many countries contains a weakened version of the poliovirus. Since 2000, the U.S. has only used an inactivated vaccine, based on a killed version of the virus and given as a shot.

The vaccine-derived virus comes from the oral polio vaccine. While the oral vaccine is effective and generally safe, the weakened virus may cause illness in people with weakened immune systems. Illness may spread when there are lots of unvaccinated people.

Widespread vaccination builds herd immunity that protects against polio

If enough people are vaccinated, the occasional traveler with wild or vaccine-derived poliovirus doesn’t cause a problem. Herd immunity is the term used to describe how vaccination protects people: if enough people are protected by vaccination, it’s hard for the illness to spread — which protects people who aren’t vaccinated.

The percentage of people who need to be vaccinated in order to stop spread varies from infection to infection; for polio, the number is about 80 percent to 85 percent. While most children in the U.S. are vaccinated against polio, vaccine hesitancy remains a problem, especially when unvaccinated children live in clusters where infections can spread. You can’t always count on herd immunity to protect unvaccinated children these days.

This is an excerpt from an article that appears on the Harvard Health Publishing website.

Claire McCarthy is a senior faculty editor as Harvard Health Publishing, a primary care pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital, and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.