Engineer Markos Hankin recovers liquid helium boil-off from Harvard labs so it can be reused.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Global helium shortage slams brakes at Harvard labs

Crisis threatens research, equipment, progress of grad students

Late spring is typically prime time for weddings and graduations, but this year a global helium shortage worsened by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced retailers like Dollar Tree and Party City to warn party planners that gas-filled balloons may be in short supply at times.

While that threatens to slightly dampen seasonal festivities, for physicists like Harvard Professor Amir Yacoby tight supplies of the noble gas in recent months actually threaten to halt research in its tracks. “This is a tremendous blow,” said Yacoby, who estimates about 40 percent of his lab’s activity has been negatively impacted. “This crisis is not going to go away quickly.”

It is one that is affecting researchers everywhere. In physics, engineering, chemistry, biology, and medical research, helium and liquid helium are employed whenever cold environments are needed for experiments, including cooling large magnets, MRI machines, or mass spectrometers, or slowing down atoms in condensed-matter physics research. Some 16 Nobel Prizes have been generated by work done using liquid helium, showing how much of a workhorse it has become in these fields because of distinct characteristics of both the gas and liquid.

At Harvard, researchers may have to shut down pieces of expensive technical equipment that rely on helium and liquid helium, the super cold liquid version of the gas. In some cases, this could cause irrevocable damage to the instruments and force some of the scientists to bring lines of research to a halt. Some ripple effects could include graduation delays for students whose thesis work depends on those projects.

“We are already in that worst-case scenario,” said FAS Dean of Science Christopher W. Stubbs. “The supply has been cut in half, so half of the experiments that rely on liquid helium have been shut down as a result. This impedes progress on both the scientific and educational aspects of our division.”

“In our lifetime it might not run out, but for humanity it has a finite supply. We can’t make any more.”

Anthony Lowe, electronics technician

Helium is the second-most-abundant element in the universe, but on Earth it’s relatively rare. It results from the decay of uranium, can’t be artificially created, and is produced as a byproduct of natural gas refinement. Only a limited number of countries produce it, with the U.S. and Russia among top suppliers. Because that’s the case, it only takes a handful of supply disruptions to trigger a crisis — the gas industry refers to the current one as “Helium shortage 4.0,” it being the fourth since 2006.

This latest shortfall began last year and started gaining steam in late winter. It was triggered by a confluence of world events, including global supply-chain problems brought on by the pandemic and worsened by the war in Ukraine, as well as planned and unplanned shutdowns at major producers — such as a mid-January leak in the U.S.’s helium reserve in Texas after a four-month scheduled shutdown and an October fire and a January explosion that closed a major Russian facility.

At Harvard, the shortage has already forced some researchers who rely heavily on the element to make painful decisions to slow down projects.

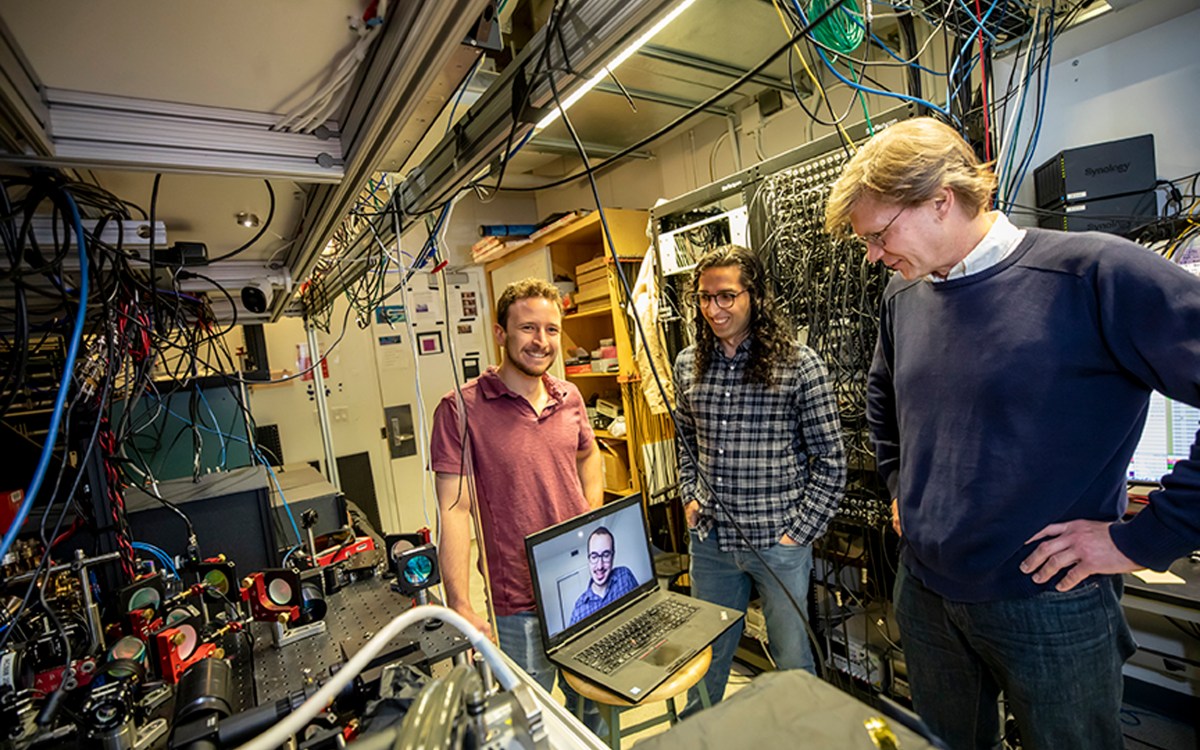

Philip Kim, a professor of physics and applied physics, says he’s had to shut down about half of his lab’s research activities that rely on cryogenic instruments.

“We use liquid helium to achieve low temperature for our experiment in several different cryostats and in applying high magnetic fields using superconducting magnets [to study the physical properties of low-dimensional quantum materials],” said Kim, whose lab goes through about 3,000 liters of liquid helium per month. “We have six cryostats [we are] actively using and had to shut off three.”

Some 16 Nobel Prizes have been awarded to work done using liquid helium.

Kim worries about the effect it will have on the research and futures of lab members.

“Graduation of my graduate students might be delayed due to slow-down of their thesis work,” he said. “Postdoctoral research fellows’ research projects are also [slowed] down as they also need to wait to be able to perform their experiments.”

Charles Vidoudez at the Harvard Center for Mass Spectrometry is starting to lose sleep over the shortage. Vidoudez, the center’s principal research scientist, uses it to keep four of the facility’s mass spectrometers at the extremely low pressures they need to be at to operate. The halt would affect dozens of labs that depend on the center to perform a range of analyses using the machines. Vidoudez has spent countless hours calling or emailing just about every supplier that he could find.

“Most just either don’t answer or the ones that do answer say, ‘We don’t take new customers at the moment,’” Vidoudez said. “It’s been a real struggle.”

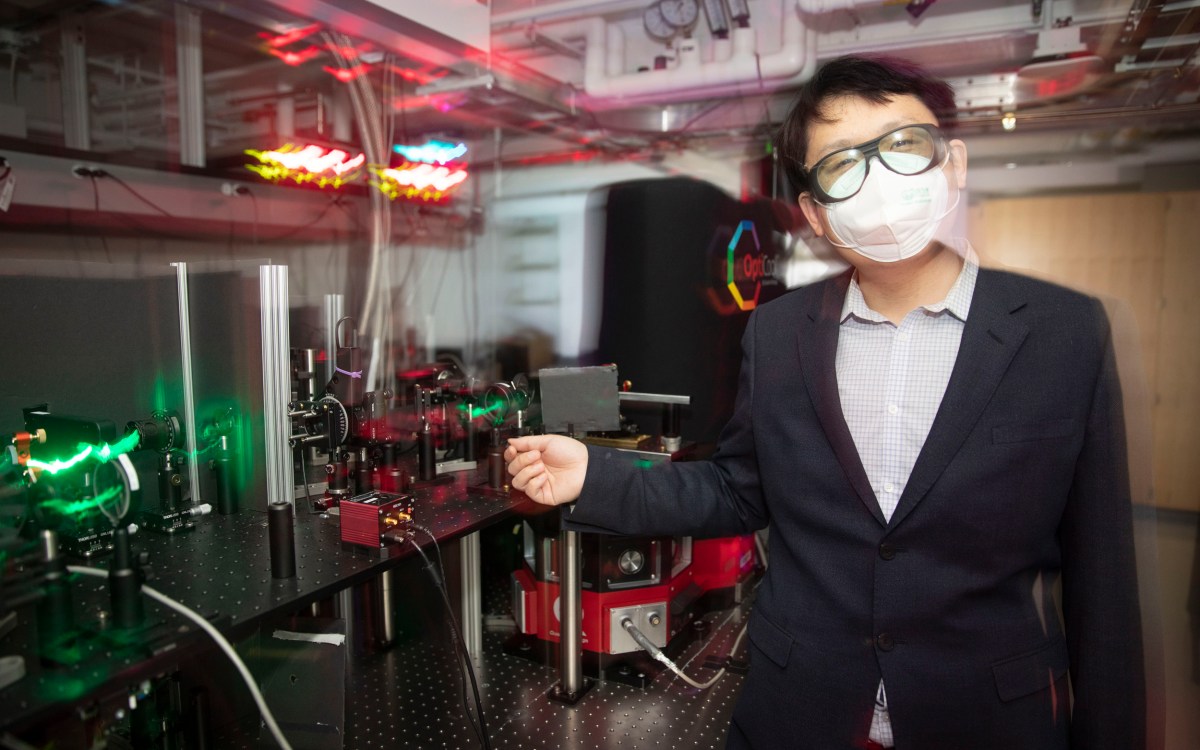

Administrators are trying to help researchers become more efficient with their use of liquid helium and reduce dependency on it. Stubbs and Sarah Lyn Elwell, the FAS Division of Science’s assistant dean for research, are co-chairing a committee focusing on helium conservation and allocation to manage their way through the crisis. There is also the division’s Helium Recovery Facility at 38 Oxford St., which came online in 2012. The facility recovers liquid helium boil-off from 12 participating labs within the FAS. It then purifies and reliquefies the boiled-off helium and dispenses it to the labs again at reduced prices.

The facility has felt the impacts of the shortage, too, said Markos Hankin, Harvard’s helium liquefier engineer. Since boil-off capture is not 100 percent, the facility must use an outside supply to make up for what is lost. Their supplier allocated them 60 percent of their usual supply. That became 45 percent by the end of March.

For now, the facility has been able to supply normal levels to labs that use small amounts of liquid helium, but it has had to ration quantities for labs like Kim and Yacoby’s. The facility is coordinating with the conservation committee as well as the University’s Strategic Procurement Office to try to find helium and develop alternate solutions.

The Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Core Facility, which supports more than 30 research groups and over 200 active researchers in the Harvard community, is one of the labs that the recovery facility has been able to keep running at normal levels because it uses only about 1,500 liters per year.

Anthony Lowe, the electronics technician at the instrumentation center, is responsible for the NMR lab’s liquid helium and helium gas supplies. He is particularly appreciative of the efforts because the liquid helium keeps the large magnets inside the spectrometers at about 450 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. Without it, they would have to ramp down the NMR magnets. The machines, whose cost range from half a million to $2 million, aren’t meant to be turned off, however, and there’s a possibility that the NMR magnets would be permanently damaged. “It’s a risky proposition,” Lowe said.

Lowe hopes the shortage gets better soon, but — like many — he worries about the future of helium in general.

“It’s a finite resource,” Lowe said. “In our lifetime it might not run out, but for humanity it has a finite supply. We can’t make any more.”