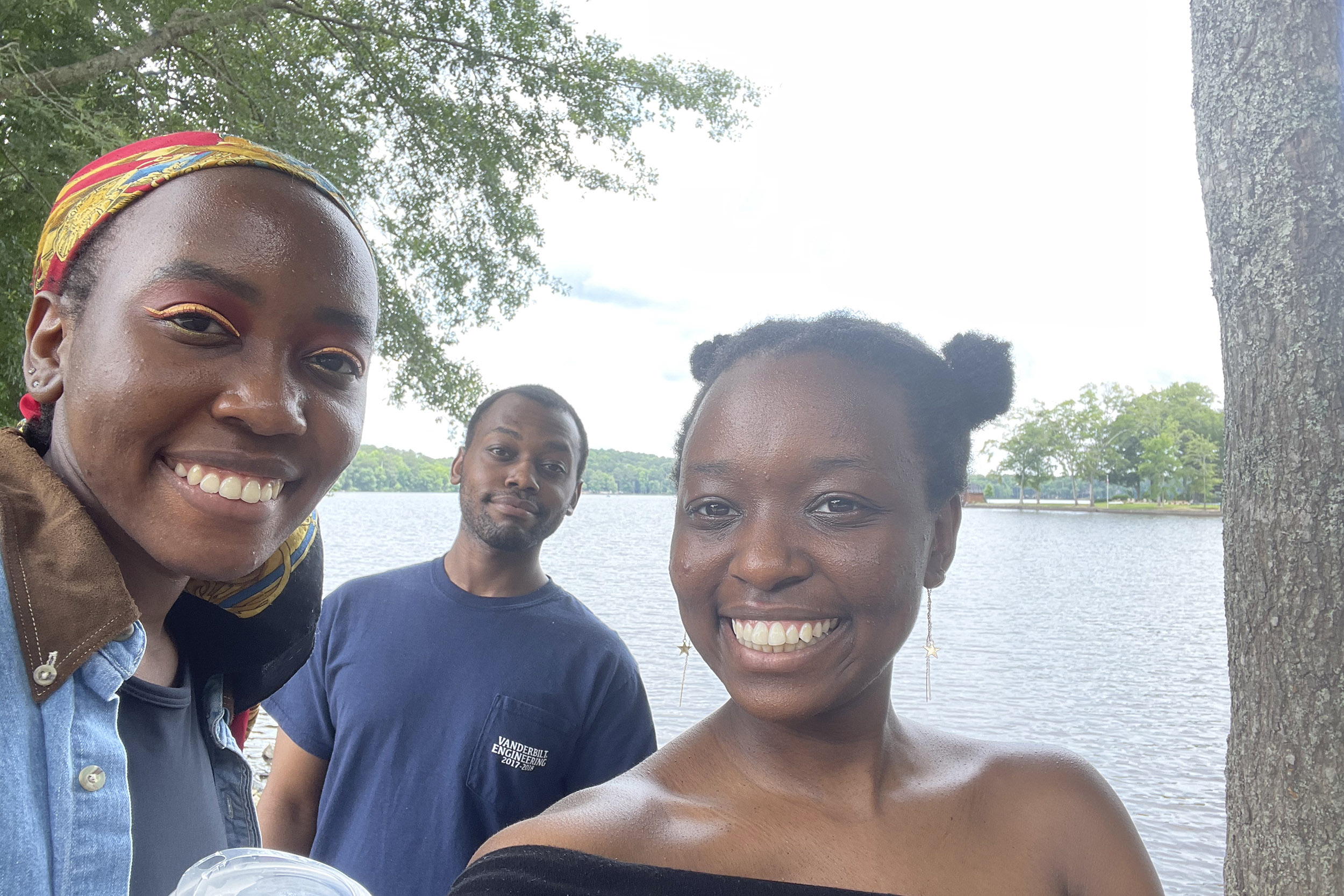

Harvard senior Anastasia Onyango (far right) with siblings (from left) Jesse, Sheila, and Brenda at a rooftop restaurant in North Carolina.

Photo courtesy of Anastasia Onyango

Good days, tough days

Anastasia Onyango, her nurse mother, first-year sister wrestled with COVID anxieties, cabin fever, reckoning over race — and brother’s board games

This is the second entry in a three-part series about family life during the pandemic. Read the first and third.

When the pandemic forced Anastasia Onyango to leave Harvard in March of 2020, she scrambled to pack up her dorm room and move home. The process was “disorienting,” she recalled. But within days, she was taking comfort in life with her family in Marietta, Georgia. The weeks and months that followed proved less than absolutely serene.

There were fears about catching the disease or infecting others, especially for her mother, a nurse. The upending of her sister’s prom, high school graduation, and start of college. The murder of Ahmaud Arbery and a reckoning on race and inequities laid bare by the pandemic. The good and bad of remote learning. Mask disputes. Cabin fever.

But there was also time for the busy family to renew bonds. They came to rely on each other for support, watching TV, taking walks, studying, cooking, celebrating birthdays and other milestones in their small pod, and enjoying just being together. Good times and tough days shared.

“[The pandemic] kind of slowed my life down a bit and reoriented me to … what mattered,” said Anastasia, pictured in Adams House, “and that was my connection with my family and my friends, and I’m really grateful.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

* * *

For Anastasia’s mom, Juliana Muthiani, the past two years have been challenging. A nurse primarily looking after older patients requiring long- and short-term care in the Marietta area, she regularly risked exposing herself to the virus and often felt helpless during the height of the pandemic as COVID-19 took its deadly toll.

“We lost several [patients], and it was so sad because they were people we had grown attached to. We take time to know each family. At some point administrators gave a line to workers to call for emotional support if they felt overwhelmed. We sent people to hospital as soon as we realized their temperatures [were] spiking or anyone who showed difficulty breathing for more advanced support and treatment. We would call the ambulance and transfer them to the hospital. But what is the hospital going to do if they are piled up in the hallways?”

Also ever present for Juliana was the fear of bringing COVID-19 home to her family.

Anastasia’s family at home in Marietta, Georgia. Brother Jesse (from left), mother Juliana Muthiani, and sister Sheila.

Photo by Kenneth L. Schneiderman

“At first, I actually wanted to leave nursing. In May and June, I stayed home … but in mid-June, I went back to work. I realized this is gonna be with us long term, and I don’t have enough savings to sit home forever, so I better just wear two or three masks and go to work.”

Juliana Muthiani

Anastasia had moved back after Harvard sent students home out of safety concerns, and youngest daughter Sheila, who graduated from high school in May 2020, ended up starting college at Northwestern remotely in fall, splitting her time between her father’s house nearby and Juliana’s home. Eldest daughter Brenda returned home for several months beginning in August before starting a Ph.D. program at Duke in 2021. And son Jesse, a 2018 Vanderbilt graduate who lived with dad, stopped by often.

“At first, I actually wanted to leave nursing. In May and June, I stayed home … but in mid-June, I went back to work,” said Juliana, who was born and raised in Kenya. “I realized this is going to be with us long-term, and I don’t have enough savings to sit home forever, so I better just wear two or three masks and go to work.”

Juliana took every precaution she could at work, wearing gloves, masks, and face shields and keeping at least 6 feet from coworkers at all times. When she got home, she would strip down in the garage, head to the shower, wash her clothes, and largely self-quarantine in her room.

As time passed, she allowed herself a little more freedom with her children but still tried to keep her distance. She permitted only immediate family into her house and spaced the furniture 6 feet apart — the way it remains today. When she wanted to join dinners or discussions, Juliana sat in the kitchen while her children gathered in the dining room.

The fear of infecting her children was a constant source of anxiety, but having them around was also the one bright spot in this dark time, she recalled. “It was good to have all of them in the same room, pandemic or no pandemic, because we don’t know when we will live again together, all of us like that.”

* * *

With help from her family, Sheila made the best of one of life’s key milestones, starting college in her small, orange bedroom in Marietta, hundreds of miles from Northwestern’s campus outside of Chicago. The typical first-year rush of new friends, dorm food, and getting lost on campus were replaced by virtual classes and meetings with professors over Zoom.

But long before high school had officially ended, Sheila knew 2020 was going to be different. In the spring, as she finalized plans for her dress and makeup, high school officials canceled her prom. She was at a salon when she heard the news. “I remember specifically mid-March is when all the school districts were starting to shut down, and it was as I was getting my hair done that I realized that prom was canceled the next day.”

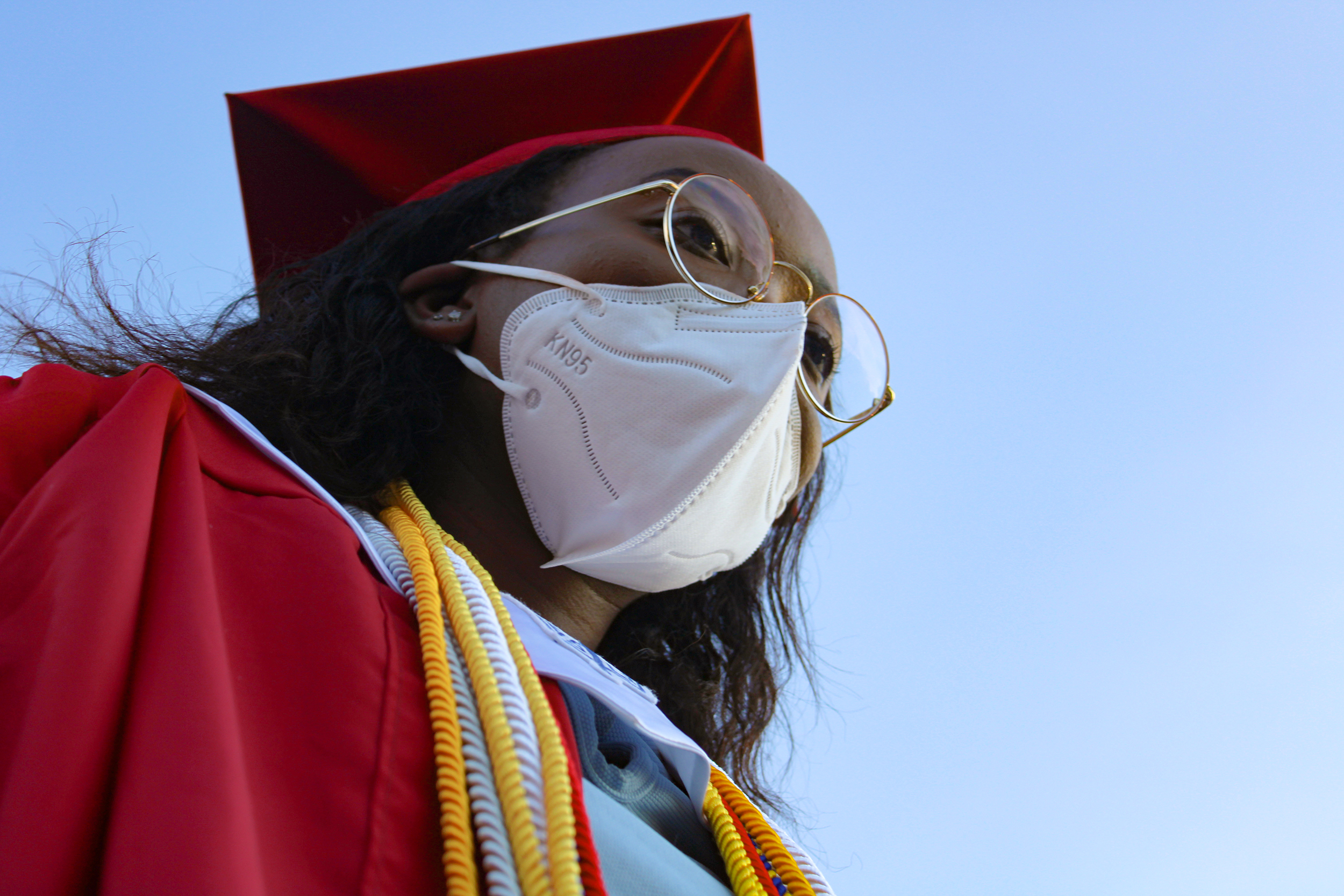

Sheila graduates from high school.

Photo courtesy of Anastasia Onyango

“That was jarring, and that was the first time that I saw how other people were in the pandemic. I think specifically because of [my mother] it also made me be really, really COVID conscious. I was like, ‘Oh my God, people are not wearing masks.’”

Sheila Onyango

Not long after, her graduation was put on hold. Officials organized a “drive-through” diploma pick-up livestreamed on YouTube, followed by fireworks in the school’s parking lot. Students were presented certificates through car windows while their names were read out on a local radio station. Sheila poked her head through the sunroof as Jesse swung his black Cadillac, decked out in Northwestern purple and white, into a long line of vehicles filled with other graduates and families. As they rolled forward, Sheila kept her mask on and refused to leave the car, unlike many of her classmates who hopped out to mingle mask-free.

“That was jarring, and that was the first time that I saw how other people were in the pandemic. I think specifically because of [my mother] it also made me be really, really COVID conscious. I was like, ‘Oh my God, people are not wearing masks.’”

Though Sheila was sad to miss out on important high school rites of passage, bonding with Anastasia during the months they spent together at home helped ease her disappointment. She remembered how, for her birthday, Anastasia and her family made a video filled with important advice about turning 18 and entering the next stage of her life. She also recalled how Brenda revamped her bedroom, rearranging furniture and adding a new bedspread, curtains, and rug to give her more “ownership over the space.”

The two sisters also revived childhood traditions, talking late into the night, taking walks to the local playground, and watching Disney and Pixar movies — albeit through a slightly more sophisticated lens. They took particular pride in their study of the animated film “Cars,” and their analysis of the film’s protagonist, Lightning McQueen, the cocky red Corvette who they determined to be a classic antihero.

When it came time for Sheila to finally head to college in January of 2021, Anastasia couldn’t hide her feelings.

“I was actually really sad because she got the news earlier that she’d be going back to campus in the spring [semester] before I did,” said Anastasia. “And I realized, ‘I’m alone. I won’t have my partner in crime.’”

Sheila (from left), Jesse, and Anastasia in Peachtree City, Georgia. The siblings sought out new nature spots to visit during the pandemic.

Photo courtesy of Anastasia Onyango

* * *

Jesse didn’t have many ties in the area and was unable to visit friends from his alma mater in Nashville. So he ended up spending a good bit of time at his mom’s house, a development welcomed by all.

It also provided Jesse with a something he desperately needed in order to indulge his passion for board games: a pool of participants made more willing by the limited availability of other entertainment options.

“During the pandemic they had been more willing to play board games with me, especially the more time-consuming ones,” he said. A favorite was Mysterium, a guessing game involving a mute ghost with all the answers, a group of psychic mediums who must cooperate to succeed, and a murder in need of solving. One review of the game includes the line: “Never a better time getting angry at your friends,” and there were moments, Jesse recalled, when that seemed apt.

“Everyone has to make their own individual choices, but you’re allowed input from everyone else.”

That process could get heated as the siblings challenged each other’s decisions.

“There were moments when the person who’s trying to choose for themselves [would say], ‘OK, I think this is the answer.’ And then another sibling [would say] ‘Well … I don’t think it is, and you’re going to lose the game for us if you’re wrong.’”

Jesse said he often watched as his sisters headed down the wrong path. But even when they lost, they lost as a team, he recalled, and it was fun just to be playing together. “Before the pandemic, we were all in our own independent spaces. But I guess … starving for human connection definitely allowed us to bond more and create those fun moments.”

* * *

Juliana describes her second-oldest daughter as a sensitive soul, and the pandemic was particularly hard for her. When Anastasia recalls her experience over the past two years, her voice occasionally trembles, and she admits the stress of worrying about her mother was difficult to endure.

“I knew my mom was in a high-risk environment, so I think that was tough because there were times when I wanted to just hug her, and I knew I shouldn’t,” said Anastasia, who will graduate with a degree in sociology and plans to follow her mother into health care.

She said she found it so “disappointing thinking about the social landscape” and the ways the pandemic disproportionately affected people of color. She added that she hopes to become a doctor to help address such disparities.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“So many of my relationships changed with friends because I realized that we didn’t really hold the same values or have the same awareness of what was going on … my support system shifted a lot during that summer.”

Anastasia Onyango

But COVID wasn’t the only thing troubling her. Anastasia and her family were sent reeling by the Feb. 23, 2020, murder of Ahmaud Arbery in their home state just as the pandemic was ramping up. Three white men chased down and killed the 25-year-old Black jogger in their South Georgia neighborhood, with the shooting death caught on videotape. In the months that followed, she feared for her brother; she grappled with whether to attend Black Lives Matter rallies; and she struggled with her decision to let go of certain friendships.

“So many of my relationships changed with friends because I realized that we didn’t really hold the same values or have the same awareness of what was going on … my support system shifted a lot during that summer.”

But her family and closest friends never wavered. “[The pandemic] kind of slowed my life down a bit and reoriented me to … what mattered,” said Anastasia, “and that was my connection with my family and my friends, and I’m really grateful.”

She also found comfort in the kitchen, cooking to relax and reconnect. She experimented with vegetarian meals, learned how to release the fragrance from spices by warming them first in oil, and prepared Kenyan recipes passed down through generations. She also helped organize cooking videos on YouTube as a way to stay in touch with her friends from Adams House. And she took up Kiswahili her junior year, which allowed her to speak with her grandmother over the phone for the first time without a translator.

“I think my values, or my priorities, shifted so much,” said Anastasia, “because I just realized how much family means to me.

“I’m just holding on to [the] stronger relationships within my family as a result of the time we spent together,” she added, “and all of the things that we had to go through.”

Most of her family will be on campus next week to watch her graduate from Harvard, and Anastasia couldn’t be happier.