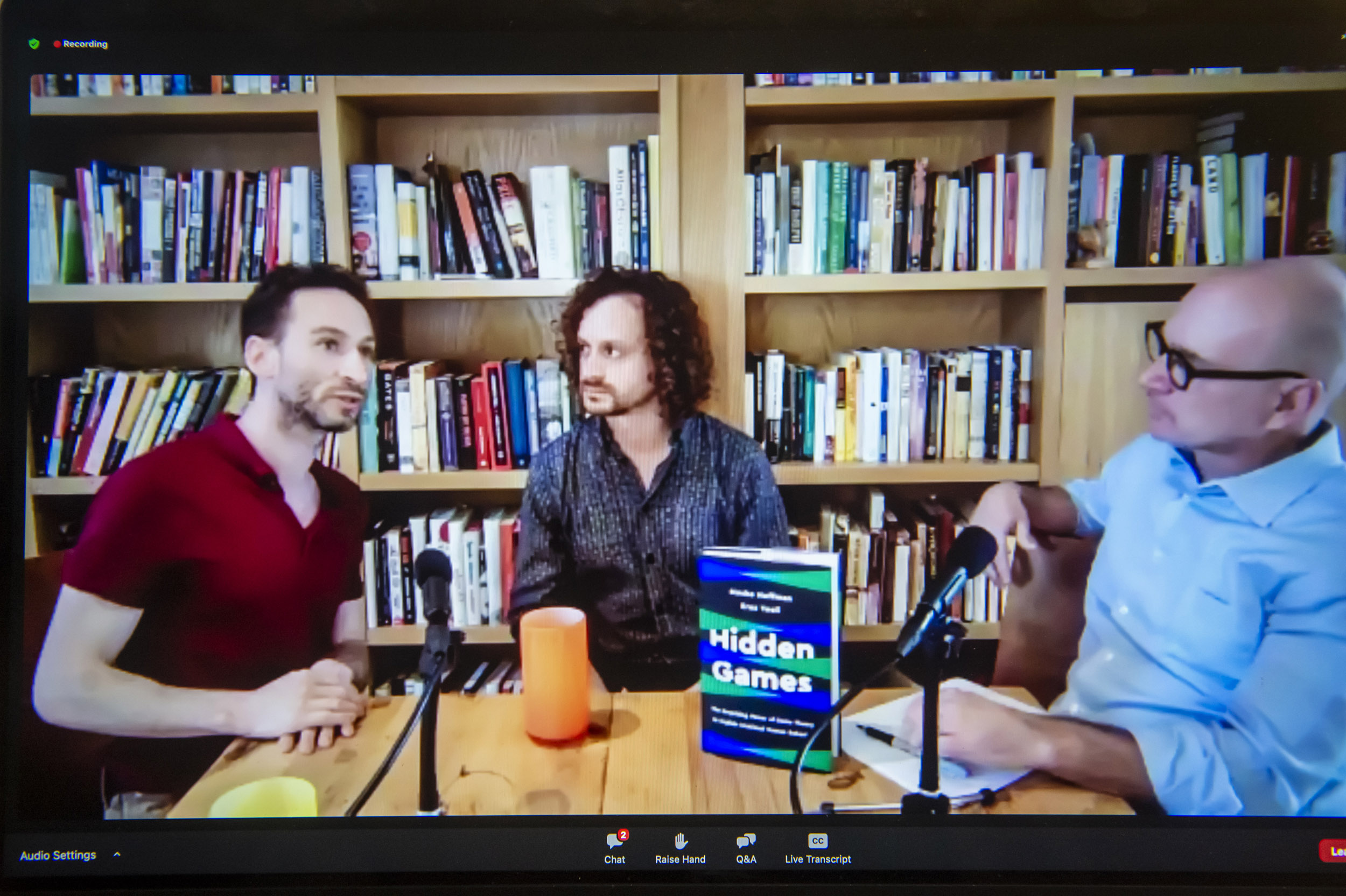

Discussing their new book, Moshe Hoffman (from left) and Erez Yoeli tell moderator Andrew McAfee that game theory can explain irrational human behavior, which operates well below the surface of our daily awareness.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Altruism may not seem to make sense until you dig deep

Harvard authors examine how game theory can help explain our hidden motivations

Game theory is the theoretical framework embraced by many mathematicians, psychologists, and economists as a tool for analyzing rational and strategic social interactions and decision-making.

But according to two Harvard scholars, game theory can also help explain ostensibly irrational human behavior, which operates well below the surface of our daily awareness, guiding our actions. In their new book “Hidden Games: The Surprising Power of Game Theory to Explain Irrational Human Behavior,” they suggest that that subconscious process can help us understand everything from our aesthetic tastes to our altruism.

Co-authors Moshe Hoffman and Erez Yoeli spoke about their latest work last week during a virtual Harvard Science Book Talk.

Game theory, they suggested, can help explain why highly politically partisan cable news shows that only present one-sided discourse or information maintain steady viewership. It’s because those tuning in aren’t interested in the expected aim of uncovering the truth, said Yoeli, a lecturer in Harvard’s Economics Department, but rather in “signaling something about a group membership, or [persuading] others that their political side is the good side.”

Hoffman, who also lectures in Harvard’s Department of Economics, said that much of human behavior is “shaped by social pressures, by either the effect you will have on other people by signaling these things, or the effect other people will have on you by positively reinforcing those behaviors.”

In the cable news example, the way the game gets hidden, they said, is when one begins to believe the spin. “You end up becoming a motivated reasoner … the social thing of trying to persuade gets internalized and ends up affecting your own beliefs in a way that it ends up being hidden,” said Hoffman, who is also a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology and a research fellow at MIT’s Sloan School of Management.

Hidden games can also help explain the real motivation behind some altruistic activities, said the authors. Take recycling. While most believe that they recycle because it helps the environment, on a subconscious, hidden level, they may be doing good for the planet because it’s good for their reputations.

In one field experiment Yoeli demonstrated that when a selfless act was more public, more people took part. Instead of having a public utility send out direct letters asking people to take part in an energy efficiency/blackout program in their building, he suggested they post a sign-up sheet in the building’s lobby. The results showed that when people got public credit for their good deeds, enrollments went up. Why? Because it’s observable, which helps build your brand, suggested Hoffman, noting that for such highly social creatures, personal brand is critical. Those with stronger reputations build more trust with others, he said, which can lead to stronger relationships and greater cooperation.

“What we are saying is that humans evolved a psychology to play these games,” said Yoeli, who is also a research scientist at the Sloan School. “They have tastes and beliefs, ideologies, intuitions, that help them do that. Sometimes those games are about reputation, sometimes they are about signaling things, sometimes they are about group identity and persuasion, sometimes they are about other things.”