A series of national surveys conducted in 1999, 2004, and 2017 provided a baseline for looking at children’s mental health, revealing some troubling underlying trends.

iStock by Getty Images

Snapshot of pandemic’s mental health impact on children

Psychiatric epidemiologist warns crisis too recent for conclusive results but shares some surprising, troubling early indications

Home from school and separated from peers during crucial developmental phases, young children and adolescents were clearly among the people most negatively impacted, in various ways, by the pandemic lockdowns. But early indications offer some additional, less-expected observations. Among them are that even before the outbreak hit there had been a trend of rising mental health disorders among young people and that some kids who were already wrestling with emotional issues actually seemed to do better during the pandemic.

Those insights formed part of the discussion by child psychiatric epidemiologist Tamsin Ford on Wednesday, as she addressed “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health,” part of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Population Mental Health Forum Series.

This crisis is still too recent for most research to be conclusive, Ford cautioned Karestan Koenen, professor of psychiatric epidemiology at the Chan School and the seminar’s host. In addition, Ford, who is affiliated with University of Cambridge, drew primarily from studies in the U.K.

A series of national surveys funded by the Department of Health in England did provide a baseline for looking at children’s mental health, however. These surveys, done in 1999, 2004, and 2017, revealed some troubling underlying trends. For example, while the physical health of children and young people up to age 24 gradually improved over this period, their mental health declined. “We were seeing a small but statistically significant increase in emotional disorders,” in particular, depression and anxiety. “And this is before we hit the pandemic,” Ford said.

What has happened since is difficult to study. A dearth of studies on children, she said, has been complicated by the problems of conducting research or large-scale surveys during a pandemic. “There’s a real issue in that we didn’t know,” she said. “All our statistical assumptions are based on having a probability sample.”

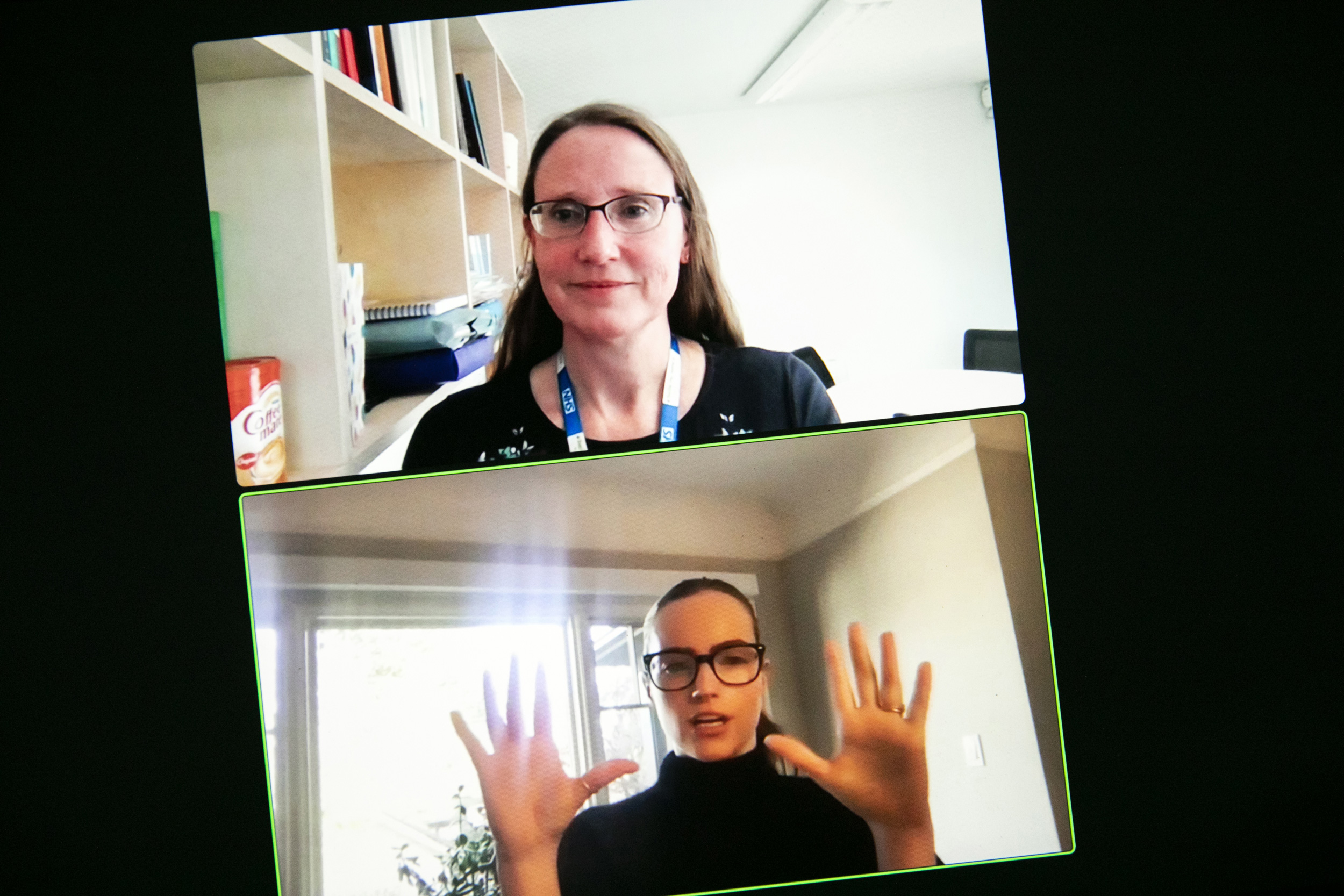

“I don’t think the schools being open is the end of the problem. It brings in some different problems,” explained child psychiatric epidemiologist Tamsin Ford (top), who spoke with Harvard Chan School professor Karestan Koenen.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Ford did share the “sprinkling of intriguing findings,” many not yet published, that she has uncovered. One study of students in England and Wales, for example, found little change in the mental health of students between October 2019, the date of the initial survey, and April 2020, during the first complete lockdown — with one exception. “When you split by mental health pre-pandemic, those who were struggling with depression pre-pandemic were doing better.”

Another U.K. longitudinal study began with a pre-pandemic baseline and then revisited subjects, collecting data monthly through 2020. The initial data from this study suggested those ages 16 to 24 were doing “particularly badly,” experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression. These issues were worst among those who were living in socioeconomic deprivation, most notably among those who were new to such deprivation, as well as those who were parents of young children.

Other studies zeroed in on particular age groups. One, focusing on children ages 4 to 10, found that the level of lockdown greatly affected mental health and behavioral issues, with England’s first complete lockdown greatly exacerbating issues from hyperactivity to depression.

Another study looked at teens, who may have felt particularly isolated during lockdown. “Peer relationships are so important with older teens,” Ford said. Without these connections, anxiety appeared to spike. More surprising, once schools reopened, Ford recalled hearing reports of fights and bullying. While such reports are anecdotal, she sees a connection. “I imagine after long periods of absence, friendship groups that would have shifted gently” under normal circumstances could have changed “quite abruptly.”

Social media may have meant that older teenagers had “a way of connecting and carrying on relationships, but it’s not the same,” said Ford. “So it wouldn’t surprise me at all if young people are anxious.

“There’s going to be a chunk of children who really struggle to get back into school,” she said, citing peer relationships and bullying. “I don’t think the schools being open is the end of the problem. It brings in some different problems.”

Overall, she concluded, the pandemic had a more severe impact on children and young people already struggling with pre-existing issues from emotional problems to socioeconomic deprivation. These problems aren’t new but “the pandemic is highlighting them and concentrating them in some populations.”

Plus, as that Glasgow study hinted, counter to expectations, some children and young adults with pre-existing mental health conditions seem to do better because of the pandemic lockdowns. “People talked about escaping from bullying,” said Ford. “They talked about repairing or improved relationships at home.” She cited responses such as “I’m sleeping better” or “I’m eating better.”

“Initially everybody was stressed and anxious, but those who could work from home, who had enough devices, and had access to the internet, they coped and began to value having more time together as a family and got into a virtuous cycle,” she said. Those who lacked resources — from food to computer tablets for at-home students — or who were already dealing with domestic violence or abuse, did worse under lockdown.

“We were all in the same storm, but we weren’t in the same boat,” she said.