A board in Tokyo captures global stock market prices falling on news Russia invaded Ukraine.

The Yomiuri Shimbun via AP Images

How invasion may hit U.S., global economies

Kenneth Rogoff sees possible fallout in stock, energy markets, worsening of inflation, increase in military spending

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sparked a global political crisis, with a humanitarian one expected to follow as civilian and military casualties mount and Ukrainians fleeing the violence create a dramatic flow of refugees into central Europe.

The attack also threatens to exact painful economic hardships. Global stock and energy markets plunged Thursday, as the invasion and widening list of retaliatory economic sanctions from the West (the most recent ones announced by President Biden Thursday afternoon) are expected to affect commodities, energy supplies in particular. Russia is a major source of oil and natural gas to Europe. The conflict is also forecast to worsen existing pandemic-related inflation, supply chain delays, and labor shortages in the U.S. and various nations around the world.

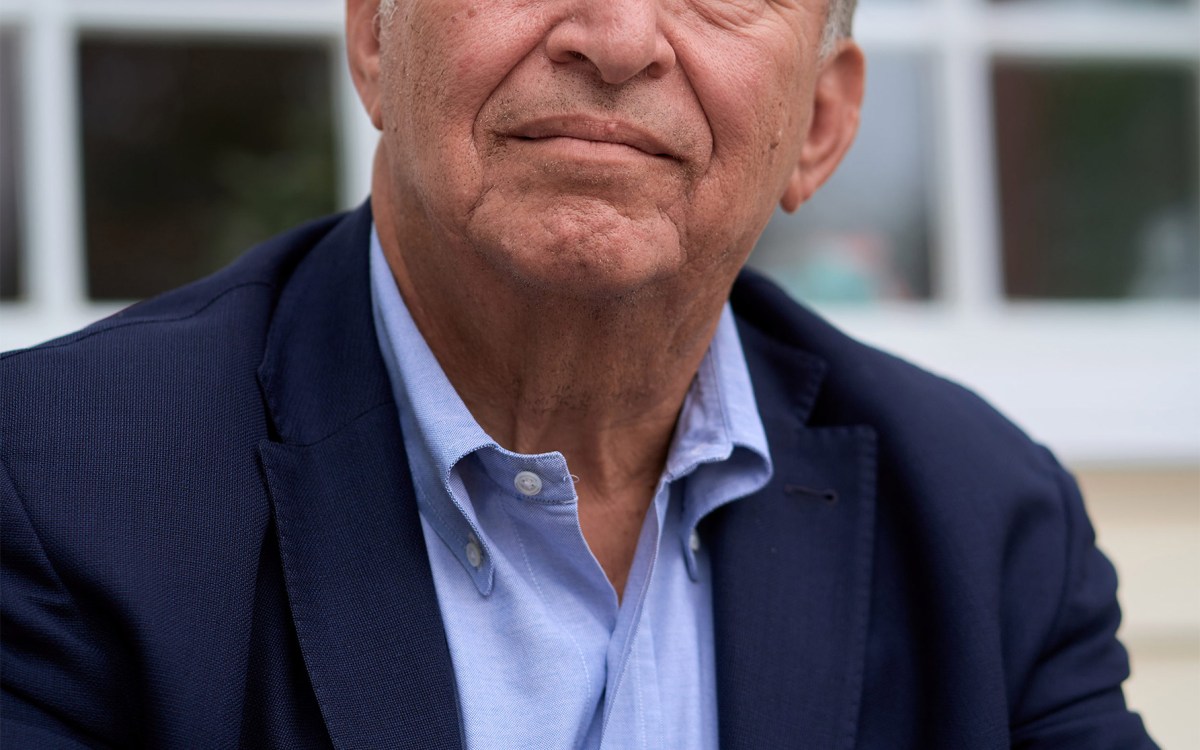

Kenneth Rogoff, Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics at Harvard, has written extensively about global financial crises. Rogoff spoke with the Gazette about how the Russian invasion and the likelihood of a lengthy war in Europe could impact the U.S. and global economies. Interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Kenneth Rogoff

GAZETTE: What risks do a war in Europe between Russia and Ukraine pose for the global economy, one that is still dealing with record inflation and supply-chain problems from the pandemic?

ROGOFF: Russia is less than a tenth the size of the United States as an economy. On the other hand, their potential to wreak havoc is enormous. A war in Europe — an open-ended situation of long-term volatility and a complete upending of the post-Cold War equilibrium — is just catastrophic. Europe already was facing massive increases in energy prices. In Germany, natural gas prices were 10 times higher this winter than before. That’s been a big driver of inflation in Europe. Russia supplies one-third of the natural gas to Europe; Russia ships 10 million-plus barrels of oil a day. That’s not going to go out of circulation, but it’s certainly pushing up oil prices to over $100 a barrel, and they could go much higher. So, there’s definitely an effect on energy prices — that’s the big one.

It’s a good bet that this is going to be bad news for food prices, if for nothing else because it’s pushing up energy prices and energy prices are a big component of food prices. More directly, Ukraine is a big producer of grain, although obviously right now it is winter, and that effect is still to come.

Russia is also a very important supplier of many minerals; there are a lot of flight routes that go over Russia. But these economic considerations are small compared to the risks and uncertainty that are being created for Europe. Where is Putin going to stop? Is he going into the Baltics? If he does threaten the Baltics, what will we do? What further sanctions are we going to put on and what is Russia going to do back to us?

Where it certainly hits is the stock market, which is likely to keep going down as this keeps getting worse. As the market falls, and as uncertainty rises, it could slow down hiring, investment, and consumption. Businesses don’t like uncertainty; consumers don’t like uncertainty, either. The macroeconomic effects have just started to unfold. Clearly, the market, although it’s nervous, is still betting that this stabilizes. For the moment, this is much worse for Europe than for the United States. But then again, so was World War I and so was World War II, and we were eventually drawn into both.

“Probably the single biggest downside for Americans is the risk of cyberwar if Russia bites back at our sanctions,” said Kenneth Rogoff, Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics at Harvard.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: What does this do to global energy markets? Is there potential for a 1970s-level energy crisis, as some fear?

ROGOFF: It’s very different. The U.S. has enormous capacity; we’re a major producer of gas and oil. At the same time, we have become much more energy-efficient. But in tackling environmental issues, the West has in some ways made itself more vulnerable. Germany’s decision to shut down all its nuclear reactors and rely more on Russian gas is looking to be a mistake of historic dimensions. President Biden’s decision to shut down the Keystone pipeline made environmental sense, but the timing has turned out to be awkward. We are going to need to ship more liquified natural gas to Europe in the long run, and they’re counting on some help now, which is going to affect gas heating prices here in the U.S. Gas at the pump is going to easily hit $4 and higher. Unfortunately, as the war deepens, and as the U.S. and Europe strike back with ever-greater sanctions, we are likely to feel it even more acutely. Probably the single biggest downside for Americans is the risk of cyberwar if Russia bites back at our sanctions.

GAZETTE: The U.S., the U.K., and E.U. have already announced sanctions and taken other punitive measures against Russian banks, Russian-owned properties, and Russians close to Putin. More are expected. Russia has shown a willingness to use cyberwarfare to attack not only governments, but critical infrastructure, banks, and private businesses. Could heavy sanctions end up boomeranging on Europe and the U.S.?

ROGOFF: Since our leaders have talked so much about putting sanctions on, it will be worse if we don’t do it. They need to follow through. Otherwise, Putin will just keep ignoring everything they say. But on the other hand, it isn’t a stable equilibrium for us to try to have perma-sanctions and treat Russia like North Korea. They’re much too important. The sanctions themselves are not sufficient. The Russians have to believe that there will be a determined military response if they push into NATO countries.

“It may not happen right away, but surely the West, and especially Europe, is going to be radically ramping up their military expenditures.”

GAZETTE: When and in what ways will American consumers start to feel the economic fallout?

ROGOFF: The immediate things they’ll feel are the stock market and higher energy prices. But the real concern would be that something hits us much faster, some kind of destabilization through cyberwar. We’ll feel the uncertainty immediately. The uncertainty may slow down our consumption, although nothing seems to have done that yet, even inflation. It could slow businesses down. The stock market falling certainly could slow down investment plans. So, you could have some macroeconomic impact from the uncertainty, no question about it.

GAZETTE: Will this situation impact the Federal Reserve’s planned interest rate hike next month?

ROGOFF: It is remarkable that the euro/dollar rate has barely budged, dropping only a percent or two so far, despite war in Europe. Interest rates haven’t moved that much, either. You get the feeling that the markets, even though there’s a lot of talk about invasion, are still very focused on the Federal Reserve. I agree with Larry Summers — that before this, the Fed was being very optimistic to believe that a 1.5 to 2 percent worth of interest rate hikes would be enough to tame inflation. This is going to slow the Fed hikes down, but not necessarily inflation. We are now even more likely to end up with inflation lasting longer because war in Europe will make the Fed’s job more difficult, no question. It is probably adding upside to inflation and downside to growth, so it’s not easy to face this.

GAZETTE: Are there secondary or tertiary effects we could experience over the long term?

ROGOFF: It may not happen right away, but surely the West, and especially Europe, is going to be radically ramping up their military expenditures. We’ve gone through this long period of a “peace dividend” where spending on military has been coming down since the end of the Vietnam War, and indeed, since World War II and the Korean War. Even an extra percent or 2 of GDP every year in higher military expenditures is going to be costly, and Europe may need to do more.

For the moment, Europe is still reeling from all their spending on the pandemic, including the sweeping next-generation euro spending, which effectively subsidized the debts of periphery Europe. I can imagine it is going to be difficult for them to digest the reality of needing to turn and spend the same again on building up their military and creating a coherent Europe defense strategy. This is not kind of productive infrastructure spending they want to be doing, nor do we, but Putin’s actions could also upend the fiscal debate here.