Celebrating the founder of Black History Month

In new book, Ed School’s Jarvis Givens tracks influence of pioneering scholar who fought to preserve record of African American life

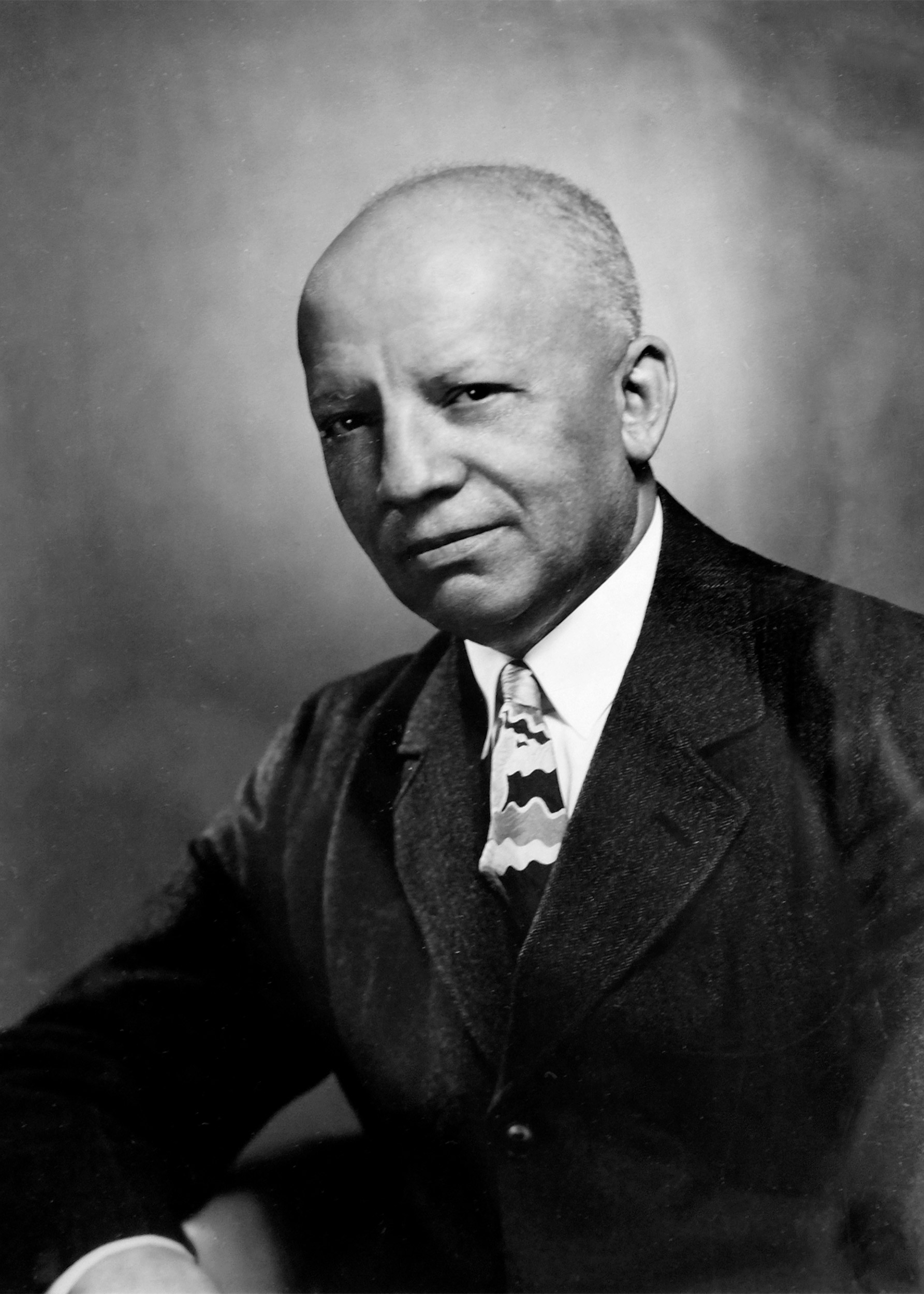

Carter G. Woodson, 1947.

Source: Library of Congress

In his book “Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching,” Jarvis R. Givens, assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, tells the little-known story of Woodson, a groundbreaking historian and the founder of Black History Month. The Gazette spoke with Givens about Woodson, who popularized Black history and joined efforts with a legion of African American teachers during the Jim Crow era to celebrate the contributions of Black people in the nation’s history. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Jarvis R. Givens

GAZETTE: Carter G. Woodson is known as the father of Black history. How did his life inform his development as a teacher, thinker, and scholar?

GIVENS: It’s always important to start with the fact that Carter G. Woodson was both the child and the student of formerly enslaved people before we emphasize that in 1912, he became the second Black person to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard. He was born in 1875 and grew up working on his family’s farm. His first teachers were his formerly enslaved uncles who taught him in a one-room schoolhouse in Buckingham County, Virginia. He worked in the coal mines before he started high school at the age of 20 and worked alongside formerly enslaved men and Civil War veterans who were illiterate, men who relied on Woodson to read to them in the evenings. It was in those experiences that Woodson came to learn that Black people carried important knowledge from their lived experiences that needed to be taken seriously and preserved. In 1915, he created the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History while he worked as a teacher during Jim Crow, and then went on to become the man that people refer to as the “father of Black history.” As an educator and institution-builder Woodson popularized Black history and celebrated the contributions of Black people in American history, and as a scholar, his books indicted the American school system for the various forms of violence it inflicted upon Black people.

“One of the biggest lessons that I hope folks take away from this book is that we can’t undervalue the significance and the impact teachers can and do have in the lives of students,” said Jarvis R. Givens, author of “Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching.”

Photo by Stephen Russell Duncan

GAZETTE: What do Woodson’s efforts represent in the history of Black education in the United States?

GIVENS: Woodson embodies a countervailing educational tradition that Black people sustained. It is a tradition that is intimately tied to the fugitive literacy practices of enslaved people who defied anti-literacy laws, which criminalized Black education, laws imposed by the white supremacist establishment determined to control and surveil them. These laws made it illegal for Black people, free and enslaved, to be taught to read and write. The first anti-literacy law was instituted in South Carolina in 1740, and it was in response to the Stono Slave Rebellion in 1739, where Colonial legislators linked Black literacy with Black revolt.

Anti-literacy laws would proliferate in Southern states during the antebellum period. Virginia, where Woodson was born, passed an anti-literacy law in 1819. I’m saying all of this to emphasize the long history of ongoing suppression and surveillance of Black education and Black teachers, but also to make clear that despite the efforts to prevent Black people from having access to education, we find stories across the South of Black people stealing away at night to learn to read and write. The most famous among these narratives is that of Frederick Douglass, who secretly learned to read and write after he learned that his education was forbidden. Douglass recalled his master’s words, that, “If you learn him now to read, he’ll want to know how to write; and, this being accomplished, he’ll be running away with himself.”

Embodied in that stolen literacy of enslaved people is a countervailing tradition that I call “fugitive pedagogy” in my book. It’s a legacy that continued to show itself after the Civil War, when Black education continued to be violently suppressed even after it was technically legal in the Southern states. Between 1866 and 1876, more than 600 Black schools were burned down in the South, which explains why Black people continued to pursue critical parts of their education subversively.

GAZETTE: How influential is Woodson’s book “The Mis-Education of the Negro” in the history of Black education?

GIVENS: “The Mis-Education of the Negro” continues to be extremely relevant. It came out in 1933, and it was a critique of American schooling and the distortions of Black life and Black humanity that existed in the established orders of knowledge. Woodson argued that such curricular violence was intimately related to the violence that Black people experienced in the physical world. In that book, he writes, “There would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom.”

But there was a bit of controversy around the book because Woodson was also criticizing some of his peers, contemporary Black scholars and leaders, for not taking a strong stance around what he saw as a central conflict in education: the condemnation of Black life in school curriculum and ideology. But the book was widely read and extremely influential, especially when we look to the emergence of Black studies and African American studies in the late 1960s. An inaugural class in San Francisco State University’s Black Studies Department, the first in the country, was called “The Miseducation of the Negro.” Many of the arguments in the book reflect core tenets of African American studies and the countervailing educational tradition that we can trace through Black people who are trying to learn to read and write against the dominant scripts of knowledge, an order of knowledge that said they were destined to be slaves, that they lacked reason, and then, that they had no history or culture worthy of respect.

GAZETTE: How did Negro History Week become Black History Month?

GIVENS: Woodson created Negro History Week in 1926 as an expansion of a set of practices that Black teachers had already been doing even before 1926. We have historical examples of Black teachers celebrating the birthdays of various Black figures, whether it be Frederick Douglass or Phillis Wheatley or the holidays commemorating Crispus Attucks, before Negro History Week. Black teachers had long developed rituals and commemorative practices in Black schools to cultivate a learning culture that affirmed Black students’ identities. It took on a new significance when Woodson offered the institutional structure of his association, where there were materials that could be created and disseminated across Black schools. But from the very first year, he reminded teachers that Negro History Week was the week not just to learn about Black history but the week to come together and celebrate what they had learned about Black life and culture in the past year. The expansion to a month took place in 1976, in the post-Civil Rights era and after the establishment of Black studies in the American academy.

GAZETTE: In a recent article, you said that anti-racist teaching is not new and that Black educators, such as Woodson and others, have long been practicing it. Can you explain?

GIVENS: The tradition of what some might call anti-racist teaching today is something that Black teachers had to engage in because it was a matter of life and death. It’s important that we not lose sight of this very rich and long legacy of Black teachers, where they continued to organize and resist, even as they found themselves in these deeply violent structures of education. In “Teaching to Transgress,” bell hooks said that “for Black people, teaching — educating — was fundamentally political because it was rooted in anti-racist struggle.”

As early as the 1860s, there were Black teachers like Charlotte Forten, a young Black woman from an abolitionist family in Philadelphia, who raised questions about the scripts of knowledge being offered to Black students. Forten taught recently emancipated Black children on the South Carolina Sea Islands. In a letter, she wrote that in addition to teaching students from the books and materials provided to her, she found it to be important to teach about the ex-slave Toussaint Louverture, who led the Haitian Revolution and freed Haiti from French colonial rule and slavery in 1804. She insisted that they should know what someone of their own color had done for his race.

My work in this area began when I encountered textbooks written by Woodson in the 1920s, such as “The Negro in Our History,” “African Heroes and Heroines,” “Negro Makers of History,” and others that highlighted the rich history and achievements of Black people, both of which were ignored or misrepresented in mainstream American textbooks. But there were textbooks written by Black teachers before Woodson. In 1890, Edward A. Johnson, a formerly enslaved man, wrote “A School History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1890” while he was a principal of a Black school in North Carolina. James W.C. Pennington, an escaped slave who went on to teach at a school for Black children in Newton, Long Island, wrote “A Text Book of the Origin and History, Etc. of the Colored People” in 1841. I think it’s important that we be clear about this long history of Black educators uplifting Black students and helping them imagine a world that had yet to exist, but one that they could strive for.

GAZETTE: What parallels did you find between your teachers, growing up in Compton, California, and Black educators from the 19th century?

GIVENS: I was blessed to have Black teachers from the time I was in preschool until I graduated from high school. My first teacher was a Black woman who was born in Grenada, Mississippi, and she asked us preschool students to memorize excerpts from speeches by important Black figures, and she taught us the words to “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the Black anthem. In high school, my AP literature teacher held 24-hour reading marathons at her home every winter break, and past and current students came to read a book together. My teachers, like many Black teachers, understood that our education was about more than individual success or social mobility, it was framed as a collective endeavor. Many of my teachers came from schools in the Jim Crow South, and they built on practices they understood to be good and necessary to provide Black students with a meaningful education. When I was writing the book, I couldn’t help but realize the resonance between what I experienced as a student and what I was seeing in the historical record.

GAZETTE: What lessons can be learned from this long tradition of Black educators challenging the system?

GIVENS: One very important lesson is that teachers have historically and likely will continue to play an important role in any efforts toward meaningful social transformation. We can’t fully understand the victories and the promise of the Civil Rights Movement and the Civil Rights struggle without thinking about the role of those teachers, who often operated in the shadows. These teachers were central to helping build and sustain that movement by cultivating the dreams of generations of Black people that we see expressed through so many of the individual figures we celebrate during Black History Month. Those folks are a part of a continuum of consciousness that can be tied directly back to the pedagogical visions of Black people striving for a meaningful, liberatory education in the 19th century.

One of the biggest lessons that I hope folks take away from this book is that we can’t undervalue the significance and the impact teachers can and do have in the lives of students. Teachers will be vital for any vision of justice we might try to build, create, and enact in the world around us.