A fossil showing the oldest swimming crab from the dinosaur era.

Photo by Daniel Ocampo

The ‘platypus’ of crabs

95-million-year-old crustacean was sharp-eyed, speedy swimmer

With its adorable big eyes, this predator seemed more Disney than deadly.

A crab roughly the size of a quarter was found in the waters of what is now Colombia 95 millions years ago. It was known for stalking its unsuspecting victims from the dark before gracefully chasing down its prey.

Today, most adult crabs are largely known as bottom-dwellers who have to scavenge and scurry across the sea floor because of their tiny, almost useless eyes. But this long-extinct crab, dubbed Callichimaera perplexa, had unique physical features that made it an agile swimmer that likely zoomed through the water to catch whatever was in its sight.

Artistic reconstruction of Callichimaera perplexa swimming after a comma shrimp.

By Masato Hattori

A new study, published in iScience, looks at the signature feature of this ancient crab: its enormous eyes that made up about 16 percent of its body.

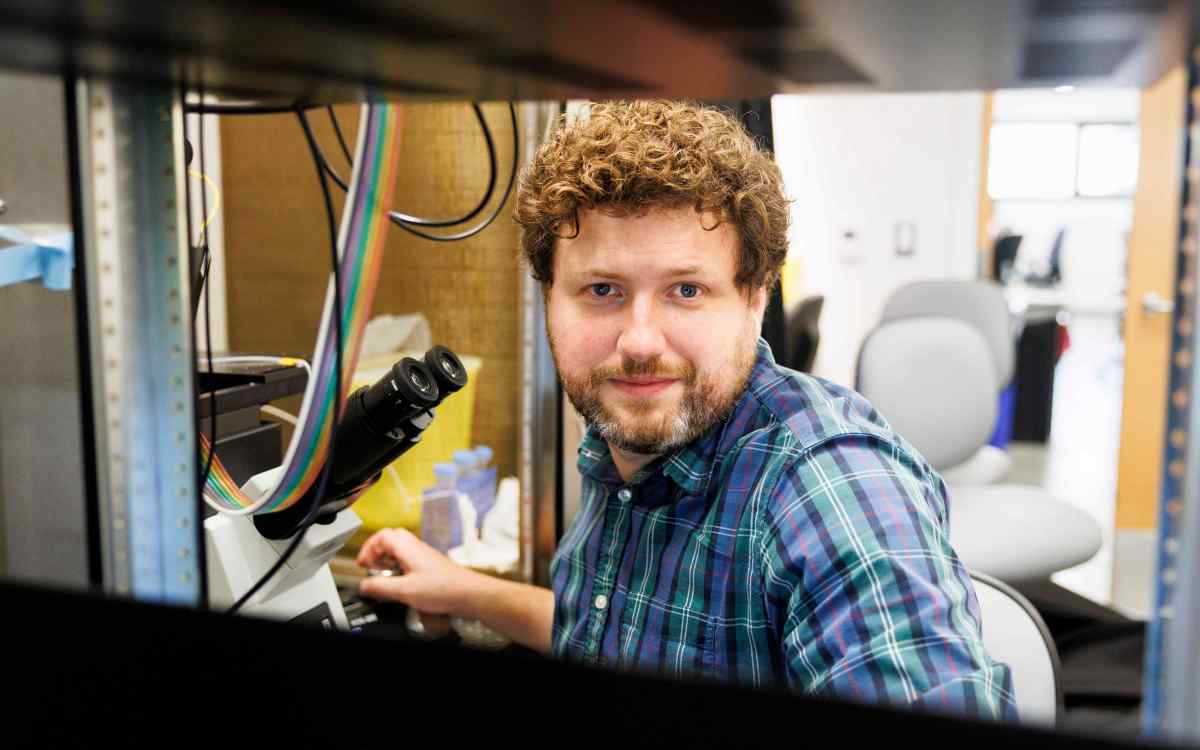

The researchers from Harvard and Yale show that, unlike most crabs today, this critter had incredible eyesight, which helped it become an active hunter.

“Even though it’s the cutest, smallest crab, the big eyes of Callichimaera and its overall body form with unusually large, oar-like legs indicate that it might have been an active swimming predator, rather than a bottom-crawler as most crabs are,” said Javier Luque, a postdoctoral researcher in the Harvard Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology.

Luque has been trying to understand Callichimaera since initially stumbling upon it on a dig in Colombia in 2005. He fondly calls it the platypus of crabs because of its unique assemblage of body parts that are present in many groups but hardly ever together in one body plan. The assortment includes a long, spider-like body with bent claws; flat, paddle-shaped legs; a strong but exposed tail; and large, stalk-less compound eyes.

“It is a true chimera,” Luque said.

Based on where the fossils have been found, it lived in what is now Colombia, Northern Africa, and in Wyoming. Luque and his colleagues have collected more than 100 well-preserved specimens. It’s unclear what type of prey the crab hunted, but it was found surrounded by fossilized comma shrimps, which are about as big as a rice grain.

Luque first described Callichimaera in 2019 in the journal Science Advances after years of periodically visiting museums and analyzing their crab fossils before confirming it was a new species.

In this recent paper, Luque and colleagues analyze seven pairs of exceptionally preserved Callichimaera eyes. They also compared them to the eyes of 15 crab species, both living and extinct, and put together a growth sequence for Callichimaera.

Luque and first author Kelsey Jenkins, a Ph.D. candidate at Yale, found Callichimaera had the fastest-growing eyes of the 1,000-plus crab specimens to which they compared them; the eyes could amount to 16 percent of their entire body. That’s equivalent to humans with eyes the size of soccer balls.

Usually, crabs have tiny compound eyes located at the end of a long stalk with an orbit to cover and protect them. Callichimaera, on the other hand, had large compound eyes with no protective sockets, meaning they were always exposed and vulnerable. The researchers said that anatomical make-up was almost a giveaway for its visual acumen.

“Plus, eyes that big impose a huge investment of energy and resources to maintain them,” Luque said. “This animal must have relied considerably on vision.”

In their analysis, the researchers found that to be true. The internal soft tissues in the eyes of Callichimaera they examined showed a closer similarity to the eyes of bees and other large-eyed insects than the stalked eyes of crabs. The researchers showed the crab saw as sharply as dragonflies or mantis shrimp, two remarkably visioned and efficient hunters.

The researchers first thought Callichimaera was a crab in megalopa, the last larval stage, where young crabs are free-swimming predators that have relatively big eyes. It’s a brief stage and as the crab matures into a juvenile, the body outgrows the eyes and the crab transforms into the sideways-scurrying scavengers seen today. The analysis showed Callichimaera was not only an adult predator, but that it maintained features from larval stages.

Luque said the researchers next plan to look at the biomechanics of Callichimaera’s swimming. Its name translating to “perplexing beautiful chimera,” Luque says he’s always surprised by what the team continues to learn about the long-dead crab.

“The animal itself is gorgeous and baffling,” Luque said. “I call it my beautiful nightmare.”