Radcliffe Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin found little scholarly work on Constance Baker Motley, who became the subject of her newest book.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Charting the path of a ‘Civil Rights Queen’

Radcliffe dean’s book explores life of social justice pioneer, lawyer, politician, and judge Constance Baker Motley

In her new book, “Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality,” Radcliffe Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin shines a light on a lesser-known, yet central player in the Civil Rights Movement and women’s rights pioneer. The daughter of working-class immigrants, Motley attended Columbia Law School, argued several cases before the Supreme Court, became the first woman of color in the New York State Senate, the first woman to serve as Manhattan borough president, and the first Black woman appointed to the federal judiciary. Brown-Nagin, who is also the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law and Professor of History, spoke with the Gazette about her new book and Motley’s lasting impact. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Tomiko Brown-Nagin

GAZETTE: How did you first hear about Constance Baker Motley?

BROWN-NAGIN: The first time I studied Motley with any detail was during the writing of my book “Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement.” She argued the Atlanta school desegregation case all the way to the Supreme Court. During the chapter that covered Motley I ended up writing a little biographical sketch, and it was within that context that I came to realize that there was relatively little scholarly work on her and thought that that was curious and something that needed to be corrected.

GAZETTE: Her life and career were shaped and influenced by the fact that she was a woman of color in a white, male-dominated world. Can you say more about that?

BROWN-NAGIN: She was a counterpart to Thurgood Marshall, known as Mr. Civil Rights. He was her mentor and hired her at a time when women just were not hired as lawyers. That was true for Motley, for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, for Sandra Day O’Connor, for many women attorneys who ended up doing great things in the law.

So, Motley’s gender was a disadvantage to her as she sought to make a career. Before she even started down that path, she had friends, even family members telling her that she was crazy, that women don’t get anywhere in the law.

On the point of seeing the Civil Rights Movement through the lens of gender, the thing to emphasize is that in Western societies, historical significance itself is essentially coded male, meaning the lives of men are deemed worthy of study and remembrance. And in this context, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Thurgood Marshall have been subjects of multiple biographies and are well-known figures in American society and throughout the world. That is well deserved in the case of those two individuals. But it shouldn’t be that women are made invisible in the story, especially when it’s such a singular woman as Constance Baker Motley, who was the only woman working at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund for many, many years, and had tremendous impact.

Another point that I make in the book is how leadership styles that are most often associated with women can be underappreciated, or conversely, how masculine leadership styles are typically prized. One of the reasons I think Motley is a little less well-known is because of her persona. She was reserved, she was imperial, she was feminine. Those traits actually facilitated her breakthroughs in the legal profession; they played well in the context of a world that was steeped in certain gender stereotypes. But at the same time, when it came to the decision about who should be the head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1961 when Marshall was stepping down, I do think that because of all of the ways in which gender limited women, including in the sense of leadership style, she was at a disadvantage. To be a leader was to be loud and gregarious and charismatic, and to be limelight-seeking and masculine. Leadership itself is gendered.

GAZETTE: Do you think that landscape has changed?

BROWN-NAGIN: I think one can say without a lot of controversy that there are still disadvantages to the extent that women do not conform to the male way of moving through the world. Those disadvantages also extend to men, frankly, who don’t conform to the masculine stereotype. I do think that at the same time, even when women do conform to male stereotypes, there are disadvantages. Behaviors that are valued in men are sometimes a target of criticism in women. And it’s really challenging to thread the needle, to retain some of those attributes traditionally associated with women that can be valuable in the workplace while also showing that one is capable of assertiveness and decisiveness in a way that is commonly associated with men.

GAZETTE: Motley had three separate careers, as a lawyer, a politician, and a judge, and throughout much of her life supported idea that progress and social change was best accomplished through the courts. Sometimes it seemed like her approach was in conflict with the direct action many others were supporting at the time.

BROWN-NAGIN: What happens is that over time norms change, ideas change, goals change around what freedom and equality mean for African Americans. When Motley started out litigating all these cases for the NAACP, initially the Civil Rights warriors were viewed as extreme leftists, even Communist radicals. By the mid 1960s, there are new radicals, adherents of Black power or Black nationalism, including in New York City where Motley is seeking public office. In that changed historical moment, she is viewed as insufficiently radical. She’s now a reformist. She is an establishment figure and an ally of white liberal Democrats. And so, in some quarters, that is held against her.

There is also an important point to make about her life in the law and the judiciary. Some allies, and even some antagonists, assumed that because she believed in social justice she would always be on the side of the little guy and rule in favor of whatever the perceived correct position was in Civil Rights cases. In fact, she was bound by legal precedent, by norms and expectations, by her own sensibilities, her own judgment about how to apply facts to the law. In that context, too, she might be deemed more pragmatic and more moderate than anyone might have thought. But that is the beauty of this project, to show complexity in the human experience and to show complexity in the African American experience and in the variety of feminisms. I make the point that Motley certainly was a symbol of — and pushed for — equality for women, especially when she was Manhattan borough president and in the New York State Senate. But she never labeled herself a feminist, which to some people is problematic. She didn’t spend time articulating her feminism. She just sort of did it in her work and in her life.

“… even when women do conform to male stereotypes, there are disadvantages. Behaviors that are valued in men are sometimes a target of criticism in women.”

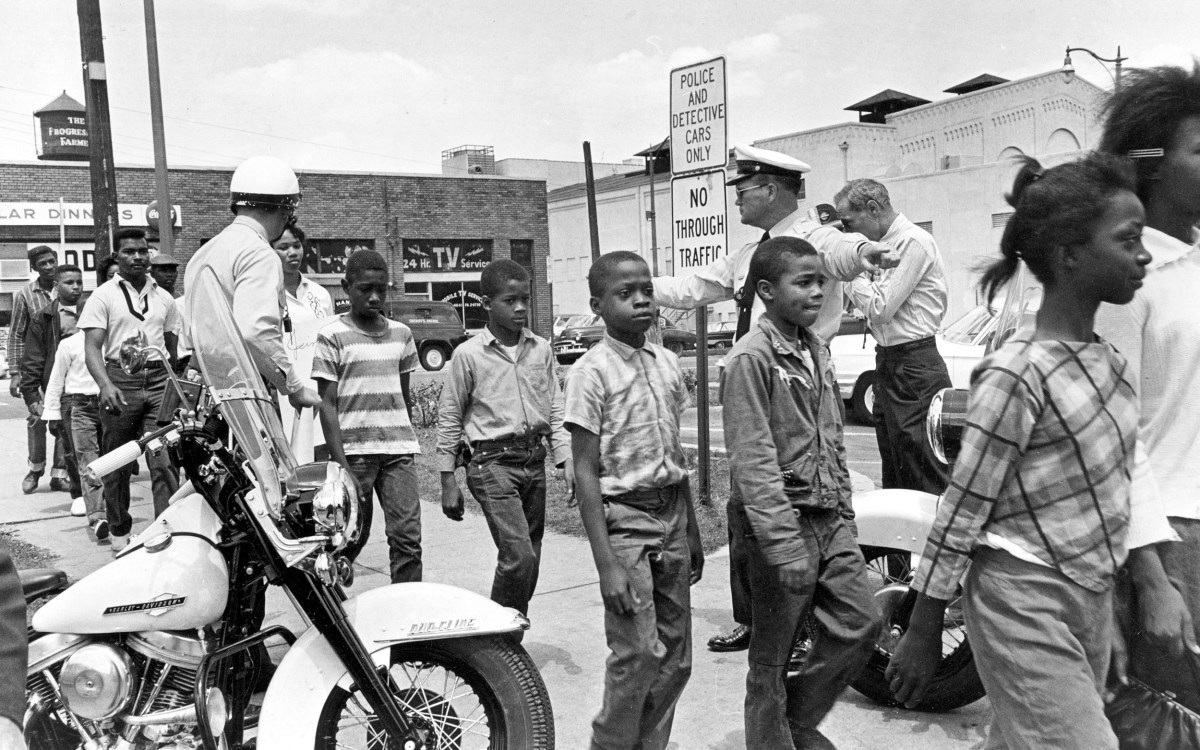

GAZETTE: So many of the issues that she was dealing with — racial justice, inequality, women’s rights, police violence and brutality, mass incarceration, voting rights — are pressing issues today. Are there lessons from Motley’s life and her body of work that we can apply to this moment?

BROWN-NAGIN: I think one overarching lesson is that while it’s important to have people of color and women who symbolize change in society, it’s foolish to expect any one individual, whether it’s Constance Baker Motley, or even Barack Obama, to be able to solve problems created over centuries. She was able to do quite a lot, but no single person can achieve the change that sometimes we want to see once a former outsider is inside the establishment. The other point is that the price for an outsider becoming an insider is that, to a large extent, one has to work within the system. The system sort of envelops the person. And that individual cannot, if he or she wants to be successful, spend all of her time pushing against the rules and norms of the system.

There is also a lesson in Motley’s life about opportunity. She came all the way from the bottom of society to the top. She, in her own personhood, teaches us a lesson about the necessity of ensuring that there is opportunity in education and employment for people from all walks of life. It was important to her to nurture talent, and she was a mentor to generations of young lawyers, even other judges, including Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Motley wanted to make sure that although she was the first in many instances, she would not be the last.

GAZETTE: Is there a direct connection between Motley’s legacy and the historic nomination, pledged by President Biden, of a Black woman to the Supreme Court?

BROWN-NAGIN: Motley appeared on short lists for SCOTUS decades ago but was never nominated. Some opponents held her experience as a civil rights attorney against her. The nomination of an eminently qualified Black woman to SCOTUS now—some 50 years later—would affirm our commitment, as Americans, to the principle of equal opportunity. Of course, Motley, working with Thurgood Marshall and other lawyers at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, litigated numerous cases that helped to establish that principle.

Supreme Court nominations are about more than partisan politics or even the balance of power on the Court, where the current conservative supermajority will remain dominant regardless of this appointment. We should not underestimate the importance of landmark nominations in building the legitimacy of public institutions. Motley made this very point when she argued persuasively for the appointment of women and people of color to the bench not because “they would bring something totally different than white men.” Instead, she said, the appointment of women and people of color to federal judgeships builds confidence in the government. It helps people feel that their government is fair.

GAZETTE: Has your time at Radcliffe influenced this work?

BROWN-NAGIN: I do want to note that this was a real Radcliffe book. I worked on it while I was a fellow, and then I completed the book while Radcliffe dean. And, of course, the book is all about gender as mediated by race and class and profession, and I am proud to send this book into the world as the head of an institution that in important part is dedicated to preserving the history of women and gender in America.

Tomiko Brown-Nagin will be the featured speaker at the first installment of Virtual Radcliffe Book Talks, 4 p.m. Tuesday. Free and open to the public, registration via Zoom is required.