Video by Kai-Jae Wang/Harvard Staff

Back in days of great floods

New research shows overflowing rivers helped sculpt face of Mars

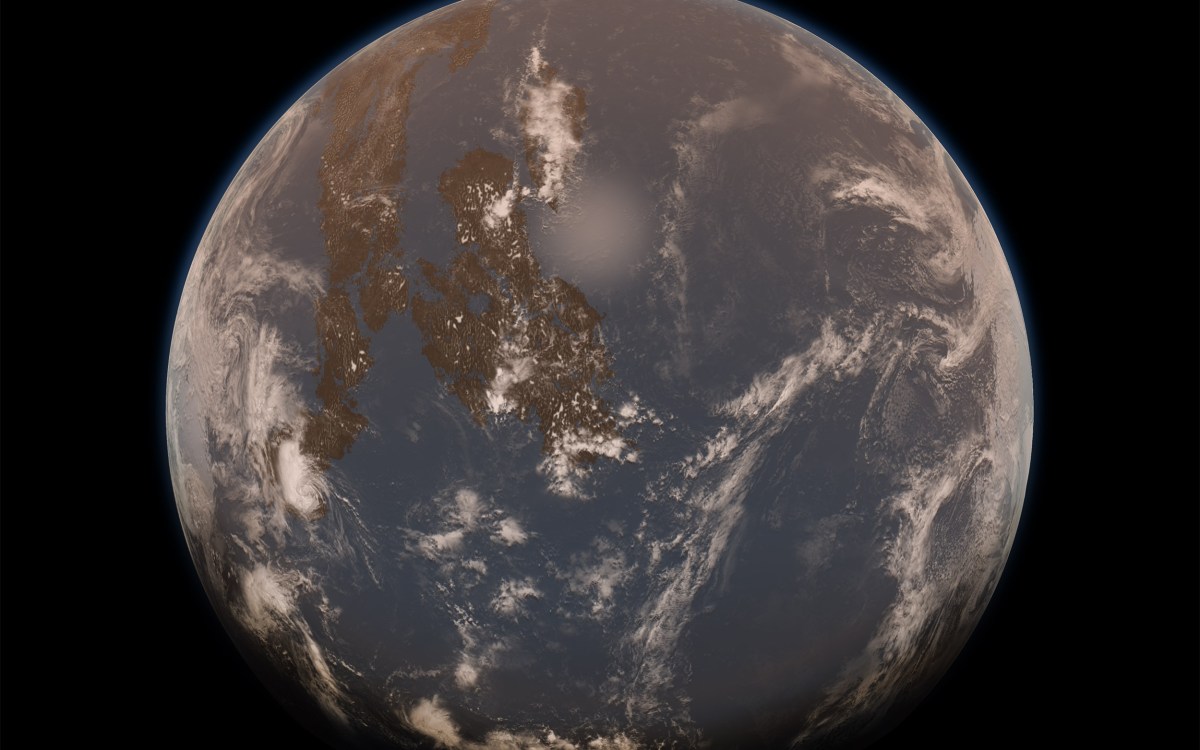

You wouldn’t know it to look at Mars now, but rushing waters that crested banks had a hand in sculpting the face of the bone-dry red planet.

New research finds that billions of years ago Mars was beset by catastrophic river flooding that played a massive role in shaping what the planet’s expansive but now dry network of valleys looks like today, with its deep chasms and canyons.

This study builds on previous work looking at the planet’s water systems and was published late last year in Nature. The project team includes Harvard postdoctoral research fellow Gaia Stucky de Quay from the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and scientists from the University of Texas at Austin.

Years of evidence show that Mars had streams, ponds, lakes, and maybe even seas and oceans around 4 billion years ago. Large river systems covered about 50 percent of the planet during this time, and large crater lakes that could hold up to a small ocean’s worth of water were common.

Scientists analyzed satellite images and sophisticated topographical mapping of these dried-up water basins on Mars to determine what happened when the lakes that used to fill the planet’s giant craters overflowed, likely due to immense rainstorms. It appears the ensuing floods loosed immense amounts of water, along with sediment.

“Mars, like the moon, is completely filled with lots and lots of craters, so you have this landscape that’s kind of like a golf ball that’s just full of little holes,” said Stucky de Quay. “What ends up happening is that all these rivers are just flowing and then fill up and then they overflow and make these catastrophic floods.”

The impact on the planet was powerful and almost immediate. Landscapes and other geological features were rapidly reshaped in a matter of days or weeks. In fact, the breach floods eroded more than enough sediment to completely fill Lake Superior and Lake Ontario.

Stucky de Quay holds a globe of Mars.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Although flood evidence has been observed previously on Mars, this is the first time that scientists have quantified how widespread it was, particularly during the planet’s early history. The study results provide scientists new insights into river formation on Mars and how it differed from the usually slow and gradual process on Earth. It also shows these types of floods on the red planet were much more common than previously thought and were an important geographical process.

“This hydrological activity was really active for some reason between 4 billion years and 3.5 billion years ago when it peaked, and we see loads of rivers that are about this age,” said Stucky de Quay. “It changes how we study these rivers because a river that forms in one day and forms a huge valley is very different from a river that formed over millions of years, so we need to reassess how we study the shapes and evolution of these river systems.”

Previous research from the group discovered that some of the crater lakes were prone to rapid flooding as a result of rainstorms and snowmelt that filled them up.

The researchers decided as a next step to look at the impact of this flooding on a global scale. For the study, they looked at images of 262 breached crater lakes that were collected by remote sensing satellites. This is believed to be the first time scientists looked at such a large number of breached Martian lakes at once.

The scientists found that the river valleys formed by these breaches were much deeper than those formed in other ways. For instance, river valleys formed by breach floods were around 560 feet deep, while the depth of valleys formed in other ways was just around 254 feet. The results suggest that these floods carved out rock and sediment rapidly while other valleys were formed more slowly.

One of the most astounding findings for the researchers was that the valley systems formed from breached lakes accounted for only 3 percent of total river valley length on Mars but made up about a quarter of its volume. That means floods from overflowing lakes carved out about 13,675 cubic miles of volume.

“This is a bit of a surprising result because they’ve been thought of as one-off anomalies for so long,” Timothy Goudge, an assistant professor at UT’s school of geosciences and lead author on the study, said in a statement.

The researchers believe the chasms and canyons that formed from flooding may have had a lasting effect on the surrounding landscape and influenced the formation of other nearby river valleys. It provides a potential alternative explanation for the unique Martian river valley topography that is usually attributed to climate.

The group hopes additional research, such as new data from the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover, will add to these findings and perhaps help pinpoint exactly how fast the floods carved out the land.

“Hopefully, we can shed some light on the timing of that,” Stucky de Quay said.