Genuine heroines

Answering Campbell’s ‘Thousand Faces,’ Maria Tatar reveals multitudes in new book

“For centuries, we’ve demonized the curiosity of women like Eve and Pandora, blaming them for bringing sin and evil into the world. Yet curiosity has served women well in our cultural imagination,” said Maria Tatar.

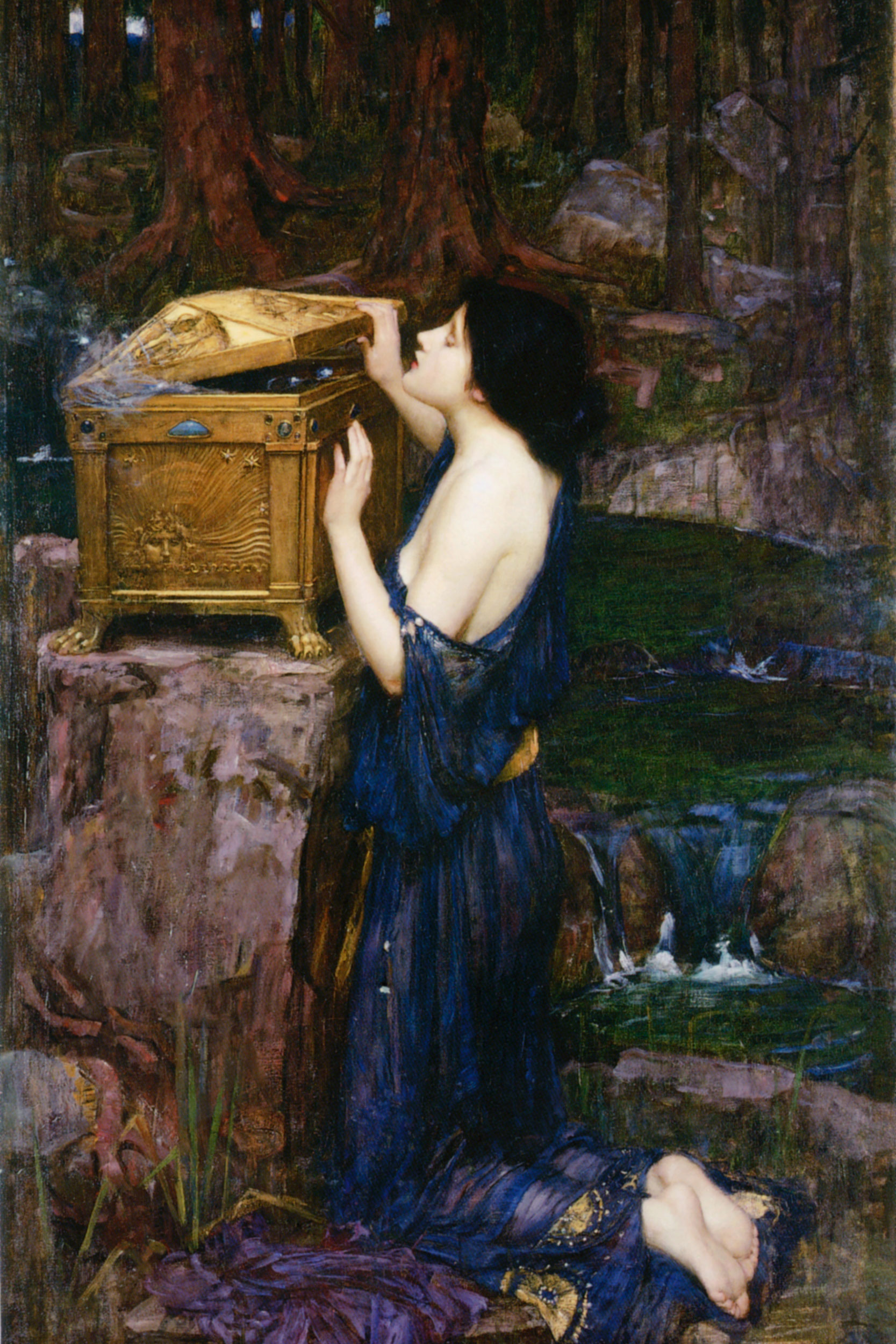

“Pandora” by John William Waterhouse, 1896

In his 1949 book “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” the literary scholar Joseph Campbell laid out a blueprint for a classic journey, one that has influenced stories from “Star Wars” to “The Da Vinci Code.” The protagonist heeds a call to adventure, goes through an ordeal, and then returns home a hero. In Campbell’s eyes, the character was almost exclusively male.

In her new book, “The Heroine with 1,001 Faces,” Maria Tatar looks beyond the warmongers, vengeful gods, and lone wolves of ancient mythology, fairy tales, and contemporary film and literature to shed light on women whose heroic feats have been ridiculed or ignored for centuries.

The Gazette spoke to Tatar, the John L. Loeb Research Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures and of Folklore and Mythology Emerita and a senior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows, about the book and her own quest to bring tales of unsung heroines to light. Interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Maria Tatar

GAZETTE: What is the story behind the book’s title?

TATAR: My goal was to capture an infinite number of possibilities for female heroism. I wanted to challenge the male-centric premise of Campbell’s book and contrast his model with what is found in Scheherazade’s heroic storytelling project in “The Thousand and One Nights.” In most cultures from times past, women lacked the mobility of their male counterparts and were confined to interior spaces, where they engaged in domestic crafts: weaving, spinning, sewing, and, most importantly, storytelling. We can detect art, craft, and beauty in the work of designing women from ancient times (Arachne and Penelope) to more recent times (Celie in “The Color Purple” or the spider in “Charlotte’s Web”).

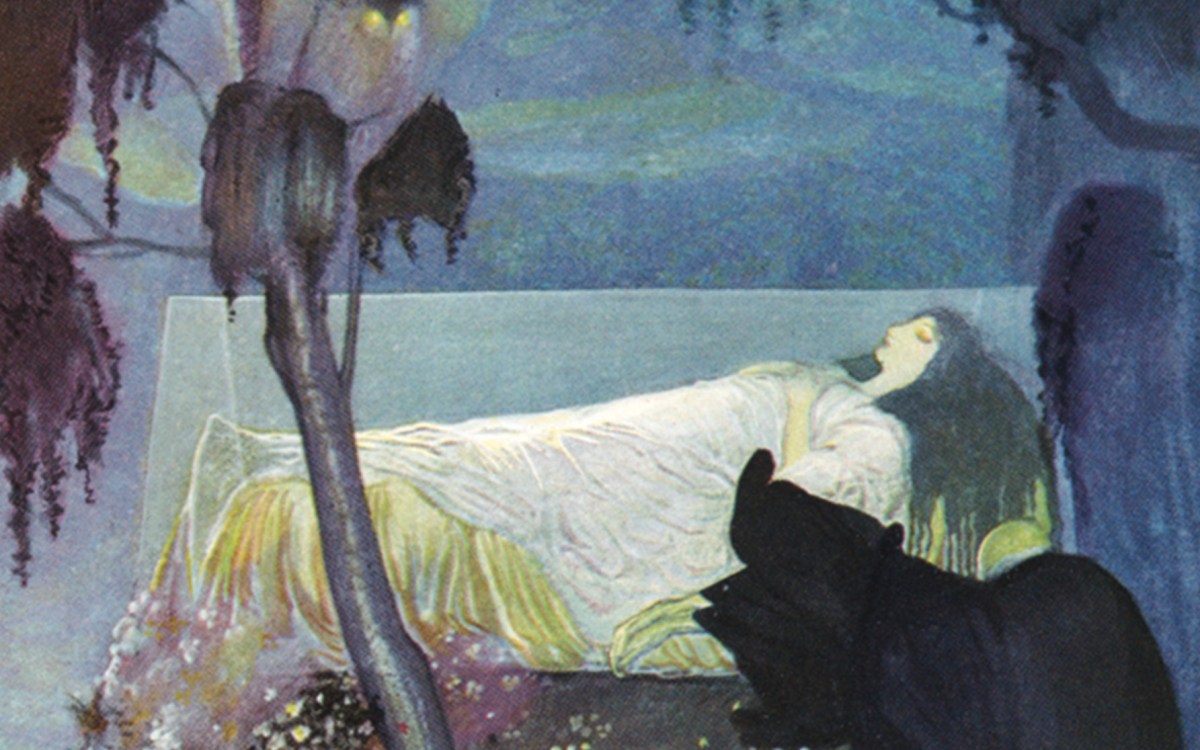

“We can detect art, craft, and beauty in the work of designing women from ancient times,” says Tatar, such as Scheherazade of “The Thousand and One Nights” and Penelope of the “Odyssey,” (both depicted above).

Images courtesy of Liveright

That’s where Scheherazade comes in as a foundational figure. She volunteers to marry King Shahryar, a man determined to punish women for the duplicity and infidelity of his first wife. Shahryar marries a succession of women, only to execute each the morning after. Scheherazade tells him stories and uses cliffhangers to delay her execution. Her storytelling prowess enables her not only to survive, but also to change the culture in which she lives; Shahryar ends his violent practices and lives happily ever after with his wife and their children. Like many heroines, Scheherazade uses words as her weapon and stories as her sword. And her goal is neither glory nor immortality, but social justice plain and simple.

GAZETTE: How did you feel when you started analyzing the ways women have survived and thrived in these stories?

TATAR: Even when marginalized, disenfranchised, and dispossessed, women managed to perform feats of heroism. Like Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre or Janie in Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” they talked back to household tyrants and seized authority, becoming authors of their own lives and putting muteness and submission on the run.

For centuries, we’ve demonized the curiosity of women like Eve and Pandora, blaming them for bringing sin and evil into the world. Yet curiosity has served women well in our cultural imagination, pushing them not just to make discoveries but also to care for others, using compassion to bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice. The heroines in my book are philanthropists in the true sense of the term. Their love for humanity leads them to work hard to repair the fraying edges of the social fabric, heal injuries, and make things whole again.

Because women’s speech was a powerful tool of resistance and revelation, it was even more important to control it or to make it impossible to speak. In “The Metamorphoses,” Ovid tells the story of Philomela and how she was raped by her brother-in-law. When she threatens to broadcast the crime, Tereus cuts out her tongue, something that, for all its horror, does not keep her from weaving a tapestry — and giving it to her sister — depicting her rape. Today’s non-disclosure agreements are in many ways just a legal strategy for silencing victims and keeping them from reporting criminal and abusive behavior.

“What I want to do is start a conversation about what it means to be a hero or a heroine today and what our models for heroism have been — and what they could be, might be, and ought to be.”

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: You write that some contemporary heroines, like Lisbeth Salander in the Stieg Larsson “Millennium” trilogy or Katniss Everdeen in the “Hunger Games,” more closely embody the Campbell archetype of the male hero than some of their predecessors, like Nancy Drew or Miss Marple. What are the benefits and challenges of this development?

TATAR: Whenever new forms of heroism emerge, I ask myself: What’s the gain and where’s the loss? The gain is that these contemporary women are charismatic, muscular, and brainy — they engage in male-coded action, leaping tall buildings in a single bound, disabling high-tech security systems, and triumphing in contests that resemble the gladiator games of ancient Rome. They can do anything a guy can do. That move in the direction of showing women in combat zones can be exciting to watch on screen. But I’m much more impressed by heroines who use the power of words, stories, and craft to track down those who injure and harm. And, by the way, men have been doing that too. But, as Madeline Miller points out in her novel “Circe,” then they are often seen as “boring.” It’s refreshing to think that we can now move on from the hero/heroine binary and consider non-gendered forms of heroism.

GAZETTE: What value do you see in reframing these foundational stories for a modern audience?

TATAR: Our foundational narratives (myths, biblical stories, epics, and fairy tales) are used not just to educate but also to indoctrinate. Maybe it’s time to stop condemning Eve’s curiosity — she is seen as a seductive creature out for carnal knowledge rather than as an agent of moral progress. Instead, we might want to highlight the courage and care of figures like Scheherazade.

Joan Didion once said: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see, and what it means.” In the 1970s and 1980s, women writers like Anne Sexton, Toni Morrison, Angela Carter, and Margaret Atwood began rewriting fairy tales, reinventing them and making them new and relevant to our time and place. Pat Barker, Ursula Le Guin, Natalie Haynes, and Miller are now doing that exact same thing with myths and epics. I’m waiting for reboots of biblical stories about Eve or Judith. Lot’s daughters, anyone? And it’s time also to pay more attention to Bluebeard’s wife and her many curious cousins in folkloric inventions. Not to mention Dorothy Sayers’ Miss Climpson or Barbara Neely’s Blanche White.

The stories we grow up with are the simple expression of complex thought. Because of that, they are great conversation-starters. In my book, I’m not trying to get at some universal truth or wisdom. What I want to do is start a conversation about what it means to be a hero or a heroine today and what our models for heroism have been — and what they could be, might be, and ought to be.