If we could talk to the animals … whales, specifically

Radcliffe fellows with divergent backgrounds came together with the goal of deciphering the clicks of sperm whales.

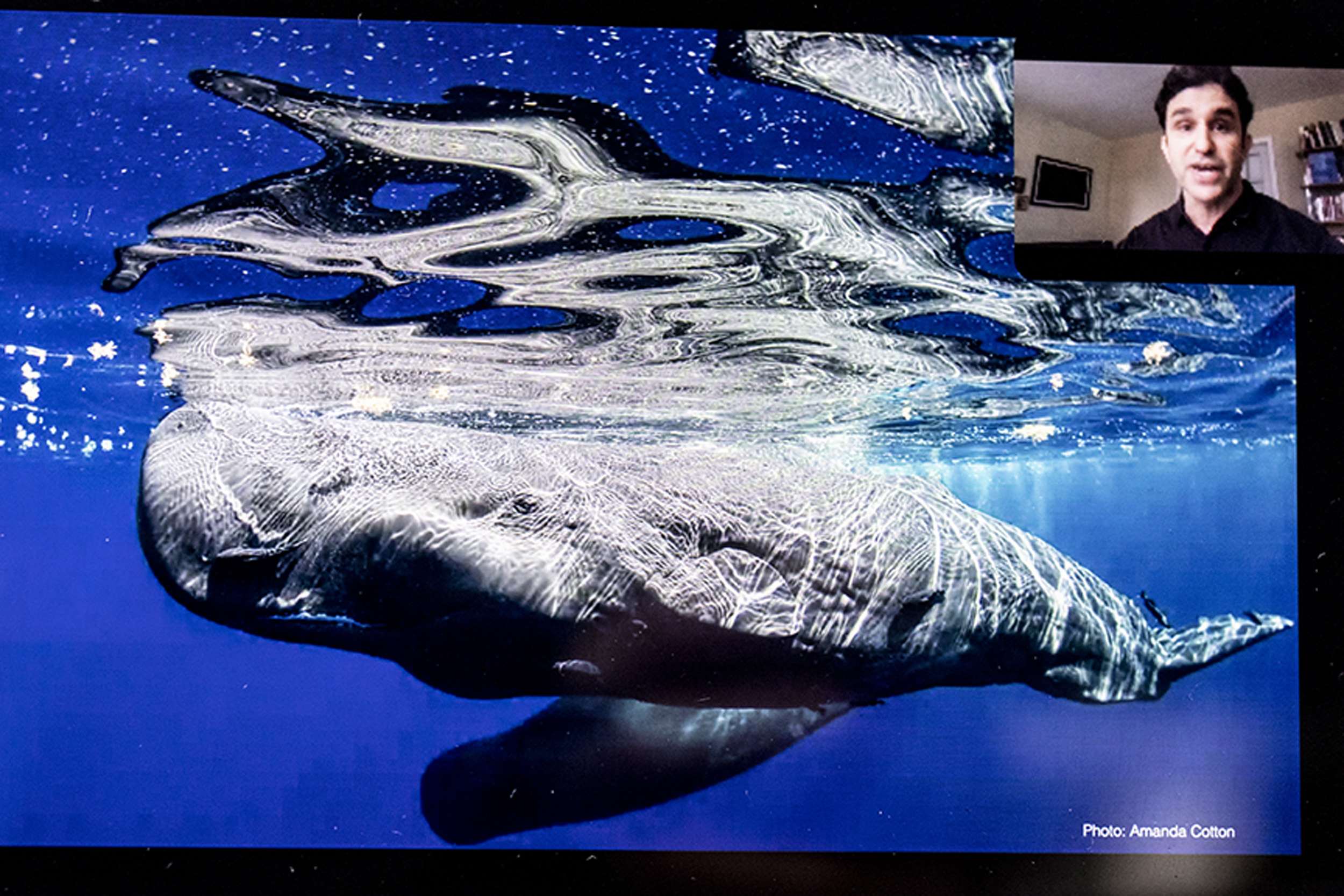

Photo by Amanda Cotton

Scientists who met at Radcliffe are exploring how whales communicate, and if they have language

If only Captain Ahab and the white whale could have had a heart-to-heart, things might have turned out differently.

It may be a bit late for the protagonists of Herman Melville’s classic novel “Moby Dick,” but talking to the massive creatures might one day be a reality. According to a group of scientists working on deciphering sperm whale communication, the time may come when a human-to-whale conversation will indeed be possible.

But first, they have to spend more time eavesdropping on the giants from the deep.

“The goal here is to find ways to use technology to connect us to nature by really deeply listening,” said marine biologist David Gruber RI ’18, lead scientist on Project CETI, a nonprofit that grew out of a series of meetings among scholars from various fields that began at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in 2017. The researchers, a collection of biologists, cryptographers, linguistics, computer scientists, and robotics experts, will begin by gathering the whale’s sounds and observing their patterns of behavior. In their final phase, they hope to play taped vocalizations back to the animals and record how they respond.

Gruber was virtually back on campus Tuesday to discuss the work with his colleagues and former Radcliffe Fellows Shafi Goldwasser RI ’18 and Michael Bronstein RI ’18. During an online talk moderated by Radcliffe Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin they reviewed the inception of CETI (short for the Cetacean Translation Initiative), its progress, and what they hope the work might mean for the future of animal/ human understanding.

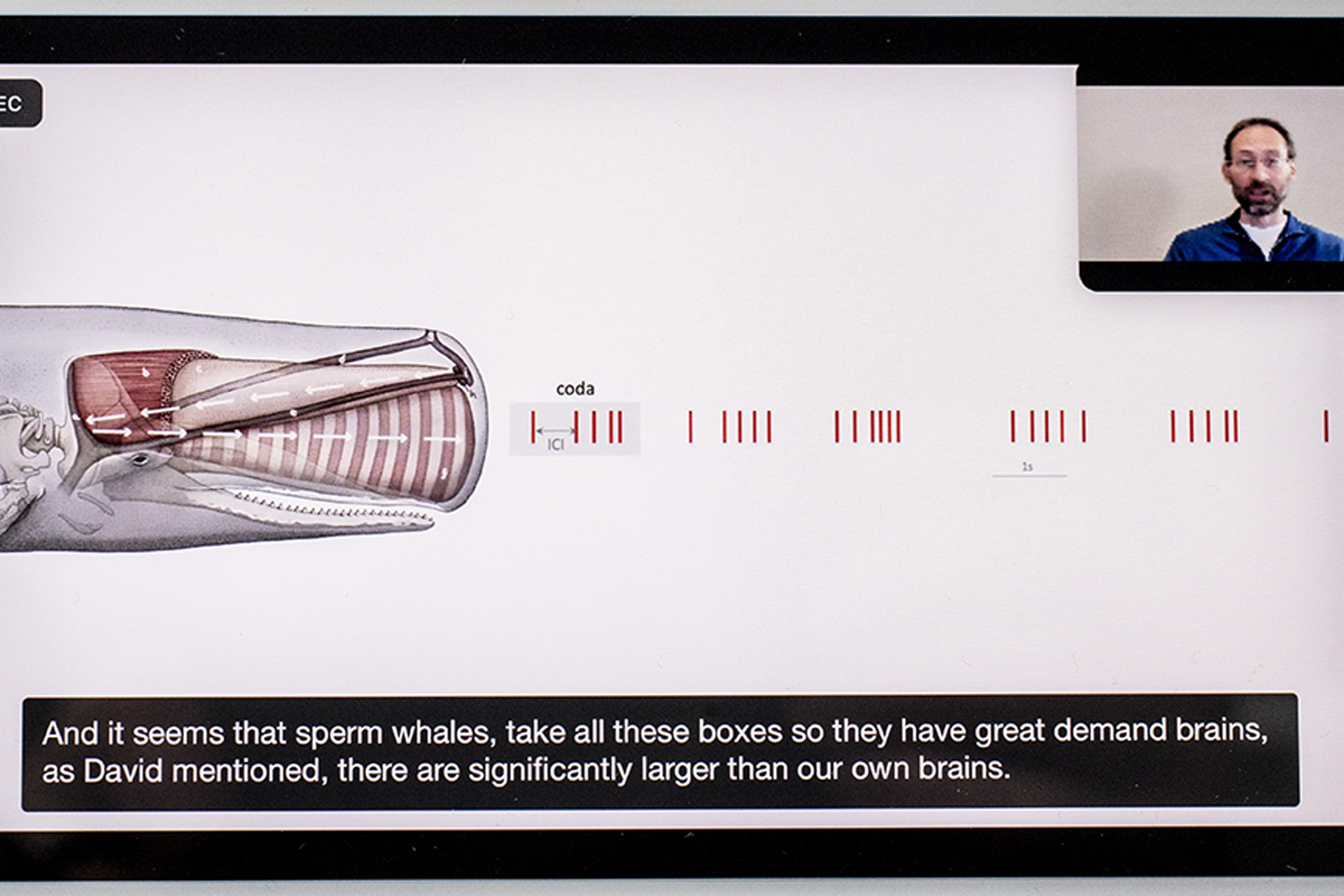

Gruber explained that while at Radcliffe in 2017 to design robots based on the soft properties of jellyfish, in collaboration with Robert Wood who directs the Harvard Microrobotics Laboratory, he grew interested in codas, the series of clicks sperm whales use to communicate. He was listening to a recording of the sounds in his office one day when Goldwasser, a cryptographer and Radcliffe Fellow exploring machine learning and data privacy, stopped in from across the hall. “We began discussing the sounds and she brought up the idea of using machine learning and invited me to this Radcliffe machine-learning working group that she’d organized,” said Gruber, a professor of biology at City University of New York.

More discussions followed, and in 2019 they applied for funding after studying an existing data set of whale sounds gathered by other researchers off the coast of the Caribbean Island Dominica and convening a two-day exploratory seminar back at Radcliffe. “We came together and kind of realized that this moment in time the window opened up where we think we could make significant inroads,” said Gruber.

Some of those inroads will be based on artificial intelligence, explained Bronstein, a computer scientist who was using his fellowship year to detect the spread of misinformation on social media sites with machine-learning algorithms when he sat in on the discussions about the giant marine mammals. Upon hearing Gruber and Goldwasser’s pitch about communicating with the leviathans his first thought was “It’s the craziest idea in the world.” But, Bronstein added, “The questions stuck in my head.”

Michael Bronstein (inset with graphic) and David Gruber said at the conclusion of their project, they hope to play taped vocalizations to the animals and record how they respond.

Photos by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Researchers have long tried to understand how animals communicate. What’s different today is the incredible advances in deep learning and artificial intelligence, said Bronstein, a professor of machine learning and pattern recognition at Imperial College London. He cited the language-generation tool GPT-3, which can produce human text on demand — answer questions, write poems, stories, essays, or news reports — as an example of groundbreaking technology that can process massive amounts of data, specifically words, with speed and accuracy. Their work will rely on a similar model.

To produce a “whale grammar,” the researchers will first collect sounds using specially designed computers attached to the animals with suction cups, underwater microphones, and swimming robots. They’ll then use traditional processors on land for the heavy computational lifting. “What is important is that we are building all these data sets for automated analysis by machine-learning algorithms rather than by humans, by hand, as it was done in the past,” said Bronstein. “And we currently estimate that it will be able to collect billions of sperm whale clicks and associated metadata that will result in a data set that is similar in order of magnitude to those used portraying human language models.”

Far from the murderous beast depicted by Melville, sperm whales are “truly gentle creatures,” said Gruber. They live in matrilineal pods in which the mothers and grandmothers dictate interactions. Those complex social lives, along with their large brains and reliance on sound to communicate at great depths — they often dive a mile below the surface and can hold their breath for more than an hour — make them ideal study subjects.

For Goldwasser, a theorist, developing a robust set of questions is crucial to the work. Through CETI, she is hoping to understand the goal of whale communication, and whether it extends beyond the search for food and efforts to simply locate one another while hunting in the deep. She is also fascinated by the ways humans “develop very complicated error correction methods for phones or computers, because there’s noise on the line,” and whether whales use similar corrections when communicating over long distances in water. Getting a better handle on the complexity of whale communication might also help scientists better understand other non-human communication and whether there is a “hierarchy of complexity” in animal communication, one possibly “connected to evolution,” said Goldwasser, professor in electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California, Berkeley.

Well aware that other researchers have long been involved in studying whale and dolphin communication, Gruber said they welcome collaboration with other scientists and with the public at large. “We’re basically putting everything up as open source, and we’re going to start a citizen science community that could help come on the ride with us.”

Acknowledging that they are just at “the beginning of this journey,” Bronstein said he hopes their work “leads to some shift in the way we treat our environment. And maybe it will result in more respect for the living world.”