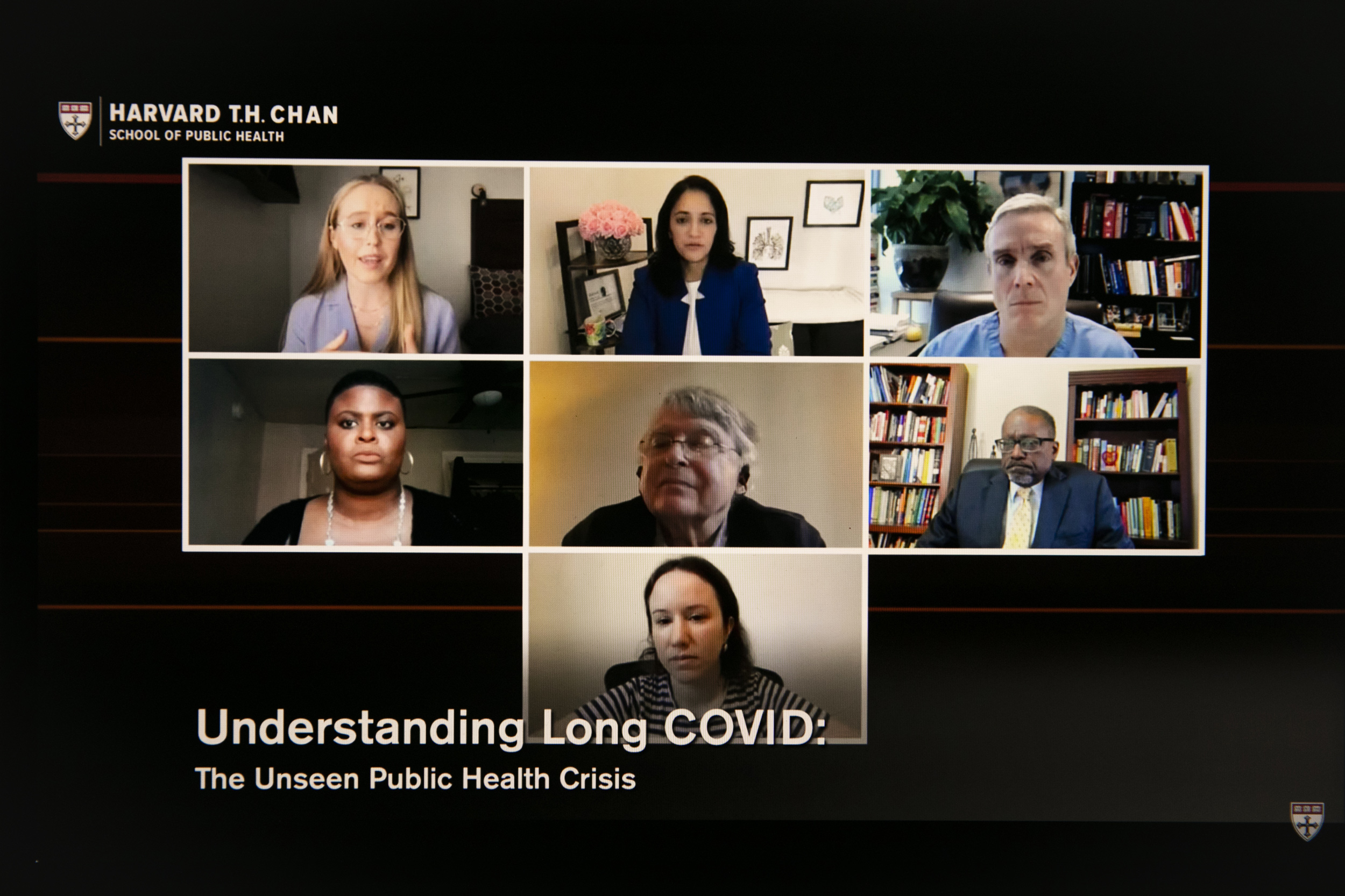

Journalist and COVID long hauler Fiona Lowenstein (clockwise from top left) moderated the virtual panel, which included Kavita Patel, Wes Ely, Gary Gibbons, Hannah Davis, Steven Phillips, and Chimére Smith.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Long COVID sufferers face physical pain, physician skepticism

Chan School event seeks way forward for patients, medical professionals

Dismissive doctors, inconclusive tests, and an array of debilitating symptoms all too often explained away as signs of mental, rather than physical, distress. That’s been the experience for many patients suffering long COVID, a poorly-defined, long-lasting suite of symptoms affecting millions of Americans.

Patient advocates and health care experts who gathered virtually at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Friday agreed that the first step in addressing the condition is relatively simple: Stop doubting patients who say they’re sick.

Patients and advocates recounted bad experience after bad experience: bouts of dizziness and vomiting, unrelenting pain, inability to stand up or get out of bed. They’ve lost jobs, experienced difficulties caring for children and themselves, and become suicidal and depressed. They’ve also faced skeptical medical professionals who insist that negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 mean they aren’t sick, that they should go home and wait it out, or possibly consider seeking mental health care.

Fiona Lowenstein, a journalist, long COVID sufferer, and founder of the patient group Body Politic, said the experience is both devastating and confusing, one of isolation and doubt. Chimére Smith, a patient advocate, said she was left to wait for hours for physicians who told her nothing was wrong and, when she described the cognitive impairment she experienced, was accused of drug use. Smith, who is African American, said she felt her diagnoses were affected not only by ignorance of an emerging condition but also by racism and sexism within the health care system.

“I would have doctors, usually white male doctors, who would look at me and say, ‘There’s nothing wrong. Everything is fine. Go home,’ and if something was wrong, ‘Just take the two weeks, and you’ll be fine,’” Smith said. “And I often think my two weeks have never come.”

“Like so many chronic disease sufferers before them, COVID long haulers face ambivalence and even outright distrust from the very health systems responsible for taking care of them.”

Michelle Williams

The virtual event, “Understanding Long COVID: The Unseen Public Health Crisis,” took place Friday afternoon and featured Smith, Hannah Davis, founder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative; Wes Ely, co-director for critical illness for Vanderbilt University’s Brain Dysfunction and Survivorship Center; Gary Gibbons, director of NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Kavita Patel, a Brookings Institution fellow, and Steven Phillips, vice president for science and strategy of the COVID Collaborative. It was moderated by Lowenstein.

“Long COVID affects millions around the globe, yet we barely understand this emerging condition,” said Harvard Chan School Dean Michelle Williams, who introduced the event. “We barely understand its devastating and long-lasting symptoms that prevent them from working, that prevent them from socializing, that prevent them from parenting, and in fact that prevents them from carrying on with any sense of normalcy. Like so many chronic disease sufferers before them, COVID long haulers face ambivalence and even outright distrust from the very health systems responsible for taking care of them.”

Even though the condition remains something of a mystery, panelists said the way forward starts with listening to — and believing —patients. From there, researchers can start cataloging symptoms — some 200 have been reported — and identify which tests have detected abnormalities, and which treatments have shown signs of helping.

Davis said despite the difficult time patients have had, it’s important that physicians and patients begin working together. It’s also important to recall that there’s a reason some never had a positive COVID test: In the pandemic’s early months, tests were scarce and unavailable to those not sick enough go to a doctor’s office or hospital. In addition, the cognitive dysfunction that many report was initially thought common only in older patients, but studies have shown it also crops up in younger ones. Davis said she finally felt heard when she visited a physician familiar with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, whose symptoms overlap.

Panelists suggested an array of solutions, including extending physician visit times, since 15 minutes is often not long enough to appropriately care for a long COVID patient; developing a list of patient questions to help guide physicians unfamiliar with the condition as they try to make diagnoses; exploring other post-viral syndromes, like that associated with Lyme Disease, for clues; convening expert groups who can begin to standardize knowledge and language around the condition so medical professionals have a common body of knowledge to draw from; and encouraging patients to stay active and insist their voices be heard.

“We have to completely think about the patient voice being a central voice,” Smith said. “The truth is, we’ve been right. We were right before. We were calling it long COVID before a lot of people. We were galvanizing [action] on social media. That’s the reason why we’re having this conversation.”