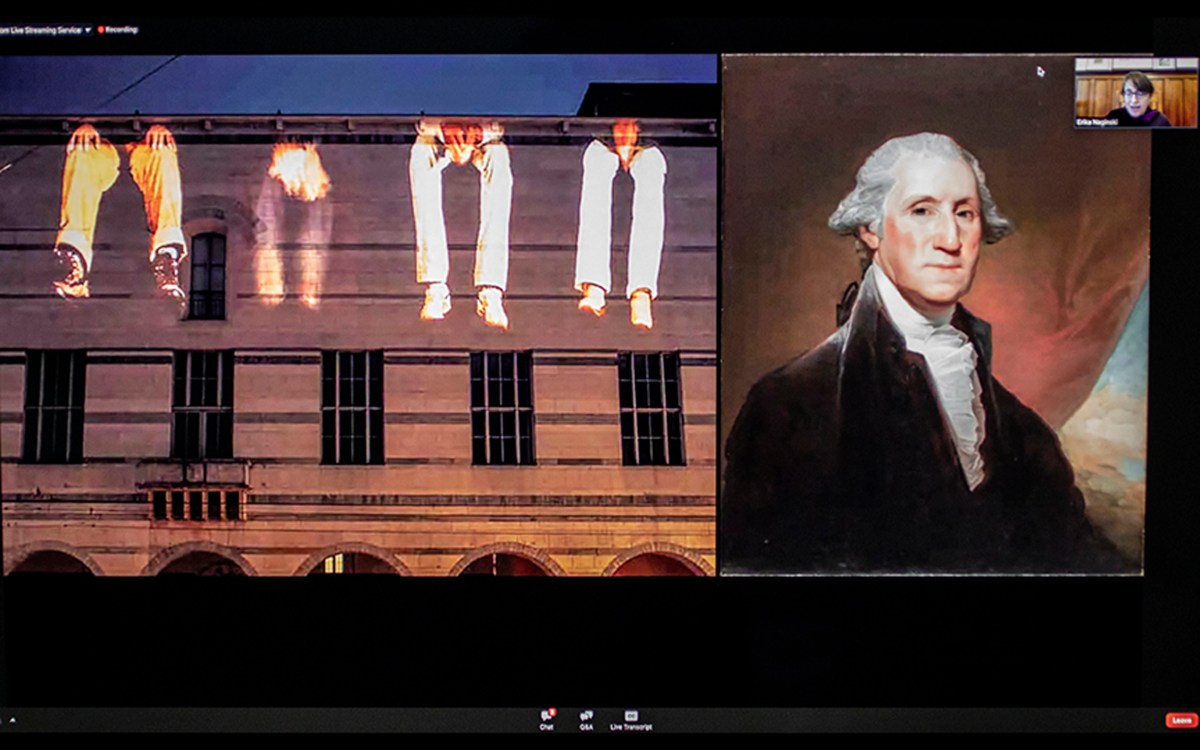

“Raphael and the Fornarina” by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (left) and “Suzanne Fourment” by Ferdinand-Victor-Eugène Delacroix were two pieces compared during the discussion. The artists were considered by many to be rivals in their time.

Photo credit: Harvard Art Museums

Competing visions

Ahead of ‘The Game,’ art historians discuss a different kind of rivalry

In the lead-up to the “The Game,” Harvard’s annual football showdown with Yale, art historians from the rival schools got into the competitive spirit.

During an online discussion sponsored by the Harvard Art Museums, Elizabeth M. Rudy, the University’s Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints, and Freyda Spira, Robert L. Solley Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Yale University Art Gallery, explored artistic rivalries through the centuries.

According to Spira, the competition between the courts of Holy Roman Emperor Maximillian I and Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, highlights how 16th-century pioneers revolutionized art with their efforts to create colored prints. The artists experimented with indigo, gold leaf, and crosshatching — the drawing of closely spaced parallel lines — to introduce color and tone to a process that until then was defined by black ink on white paper.

One well-known historical rivalry was more a product of hype, said Rudy, referencing the alleged clash between French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix and French Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Many critics insisted the artists fell into two separate camps: the color and pigment favored by Delacroix versus the drawing and line preferred by Ingres. While Delacroix loved the works of Peter Paul Rubens, a Flemish master of color, and Ingres was obsessed with the High Renaissance Italian Raphael, whose work was exemplified by line, scholars have debunked claims that the artists were “the figureheads of two identifiable movements,” said Rudy. “They were complete dialectical opposites.” Still, stories of personal animus proved popular fodder for the press, helping fuel the myth.

Curators Elizabeth Rudy (right) and Freyda Spira.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“The story of these two artists’ similarities and differences is complex and entangled,” said Rudy, “but there’s something about the simplicity of a face-off, of a clear opposition that satisfied the public, and I daresay it does today.”

Rivalry can also be a great source of creativity, she noted, particularly in the architectural realm. She offered up the example of a 1922 design contest for a new headquarters for the Chicago Tribune. The competition received more than 260 submissions from 23 countries. The winning idea, a neo-Gothic design by New York-based architects Raymond Hood and John Mead Howells, is still a fixture of the Chicago skyline — but one of the losing drawings had an even greater impact.

When sketches for the competition were published in a book a year later, a submission by Adolf Meyer and his partner Walter Gropius, who founded the revolutionary 20th-century German school known as the Bauhaus, caused a stir. Their vision of a sleek geometric skyscraper “sought to be thoroughly modern without explicit references to past historical form,” said Rudy, and their approach “would be adopted by subsequent generations of architects, and today the style dominates many urban landscapes.”

Gropius eventually joined Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. His Tribune competition drawings and photographs are included in the collection of Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger museum, which houses the Gropius Archive and the largest Bauhaus-related collection outside Germany.

“There’s something about the simplicity of a face-off, of a clear opposition that satisfied the public, and I daresay it does today.”

Elizabeth M. Rudy

Almost 60 years after the Chicago competition, an undergraduate at a school a little south of Cambridge would design a transformative war memorial. In 1981, Maya Lin was a senior at Yale when her design was chosen for a Washington memorial honoring U.S. service members who died in the Vietnam War. Selected from more than 1,400 submissions, Lin’s “minimal plan,” said Spira, “was in sharp contrast to the traditional format for memorials, which usually included figurative heroic sculpture.”

Instead, Lin envisioned a “V-shaped form that would be literally carved into the landscape” of the National Mall, one that would relate directly to the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial and “tie the three together physically and historically.”

As a Washington, D.C., native, Spira said she considers Lin’s final product, a black granite wall engraved with the names of more than 58,000 dead or missing “one of the most significant and emotive on the Mall.”