Artistic reconstruction of the new fossil dubbed Cretapsara athanata, “the immortal Cretaceous spirit of the clouds and waters.”

Artwork by Franz Anthony, courtesy of Javier Luque/Harvard University

Bad for 100-million-year-old crab, but good for scientists

Crustacean trapped in fossilized tree resin offers clues into evolution of creatures, when they spread

Javier Luque’s first thought while looking at the 100-million-year-old piece of amber wasn’t whether the crustacean trapped inside could help fill a crucial gap in crab evolution. He just kind of wondered how the heck it got stuck in the now-fossilized tree resin?

“In a way, it’s like finding a fish in amber,” said Luque, a postdoctoral researcher in the Harvard Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. “Talk about wrong place, wrong time.”

It was, however, a bit of good luck for Luque and his team, as the amber, recovered from the jungles of Southeast Asia, presented researchers with the opportunity to study a particularly intact specimen of what’s believed to be the oldest modern-looking crab ever found. The discovery provides new insights, reported Wednesday in Science Advances, into the evolution of these crustaceans and when they spread around the world.

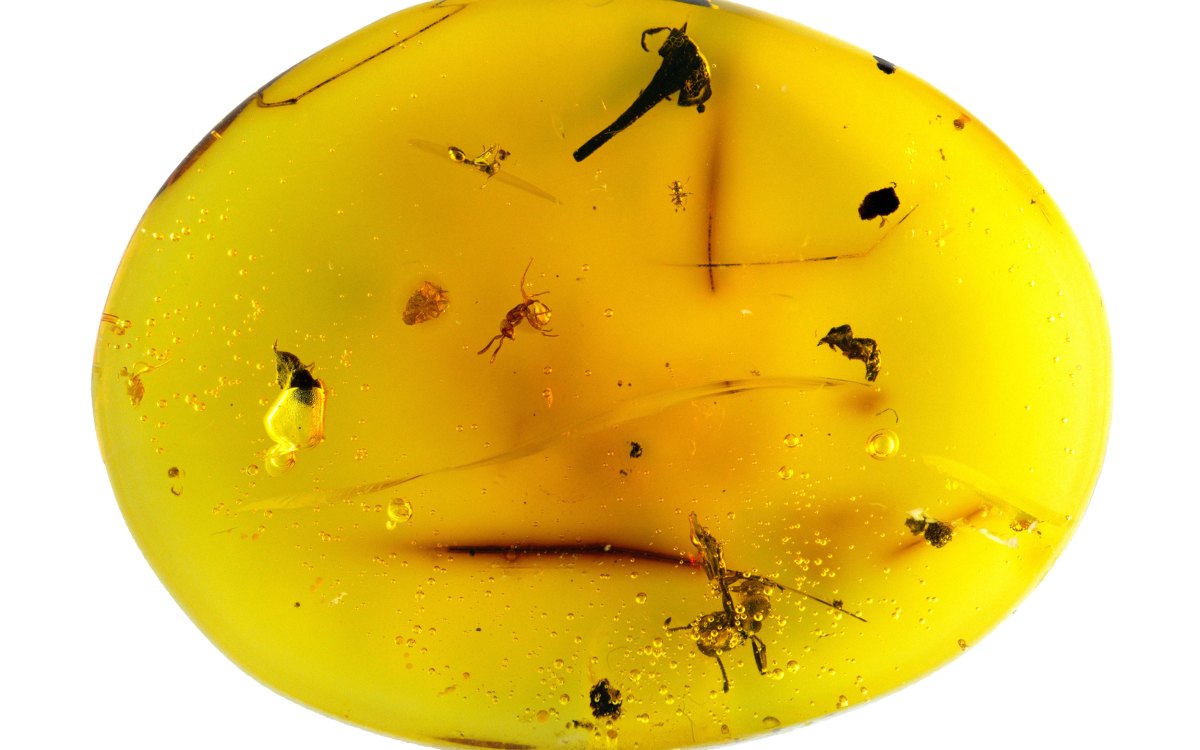

The crab, measuring about the width of an eraser on a pencil, is the first ever found in amber from the dinosaur era, and the researchers think it represents the oldest evidence of incursions into nonmarine environments by “true crabs.”

Researchers describe this as the most complete fossilized crab ever discovered.

Credit: Lida Xing/China University of Geosciences, Beijing

True crabs (known as Brachyurans) stand in contrast to “false crabs” (called Anomurans) that aren’t technically crabs but are still sometimes called by the name (think hermit crabs or king crabs).

Previous fossil records, which mainly consist of bits and pieces of claws, suggested that nonmarine crabs came onto land and into freshwater about 75 to 50 million years ago. This new discovery pushes that back to at least 100 million years ago, answering Luque’s initial question of what this crab was doing in the jungle and bringing the fossil record in line with long-held theories on the genetic history of crabs.

“If we were to reconstruct the crab tree of life — putting together a genealogical family tree — and do some molecular DNA analysis, the prediction is that nonmarine crabs split from their marine ancestors more than 125 million years ago,” Luque said. “But there’s a problem because the actual fossil record — the one that we can touch — is way young at 75 to 50 million years old … So this new fossil and its mid-Cretaceous age allows us to bridge the gap between the predicted molecular divergence and the actual fossil record of crabs.”

The researchers now believe that what is known as the Cretaceous Crab Revolution —when crabs (true or not) diversified worldwide and started evolving their characteristic, crabby-looking body forms — was not a one-time event, as previously thought. This new research brings the tally of when different crab species independently evolved to live outside their marine habitat to at least 12 separate times.

Video credit: Alex Duque, courtesy of Javier Luque/Harvard University

The new fossil was dubbed Cretapsara athanata, “the immortal Cretaceous spirit of the clouds and waters.” The name honors its age and South and Southeast Asian mythological spirits. The creature suspended in amber is instantly recognizable as a true crab, which makes sense since the researchers say it is the most complete fossilized crab ever discovered.

The team, using micro-CT scans, was able to see in clear detail delicate tissues like the crab’s antennae, legs, and mouthparts lined with fine hairs, large compound eyes, and even its gills. Not even a single hair was missing, they said.

The study was a collaboration between Harvard and the China University of Geosciences, and included authors from 10 institutions including Yale University, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institution Panama, University of Alberta, UC Berkeley, Yunnan University, and the Royal Saskatchewan Museum.

The work is part of a larger National Science Foundation-funded project with Javier Ortega-Hernández, an assistant professor in OEB and curator of invertebrate paleontology in the Museum of Comparative Zoology; Joanna Wolfe, a researcher in Ortega-Hernández’s lab; and Heather Bracken-Grissom from Florida International University to investigate the evolution of crabs over 200 million years.

The fossilized amber specimen is housed at the Longyin Amber Museum in China. The piece was collected by local miners in Myanmar, and purchased legally in 2015. In the paper, the authors acknowledge the sociopolitical conflict in northern Myanmar and say they have limited their research to material predating the 2017 resumption of hostilities in the region. They hope acknowledging the situation in the Kachin State will serve to raise awareness of the current conflict in Myanmar and the human cost behind it.

Javier Luque (left) and Catalina Suarez excavating fossils in the tropics.

Credit: Felipe Villegas/Humboldt Institute

Luque, who has been studying crab evolution for more than a decade, said he first became aware of the specimen in 2018 and has been obsessed with it since. He hopes the finding will make people consider crabs deserving of another moment in the spotlight.

“They are all over the world, they make good aquarium pets, they’re delicious for those of us who eat them, and they’re celebrated in parades and festivals, and they even have their own constellation,” Luque said. “Crabs in general are fascinating, and some are so bizarre-looking — from tiny little pea-shaped crabs to humongous coconut crabs. The diversity of form among crabs is captivating the imagination of the scientific and nonscientific public alike, and right now people are excited to learn more about such a fascinating group that are not dinosaurs. This is a big moment for crabs.”

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Geographic Society, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.