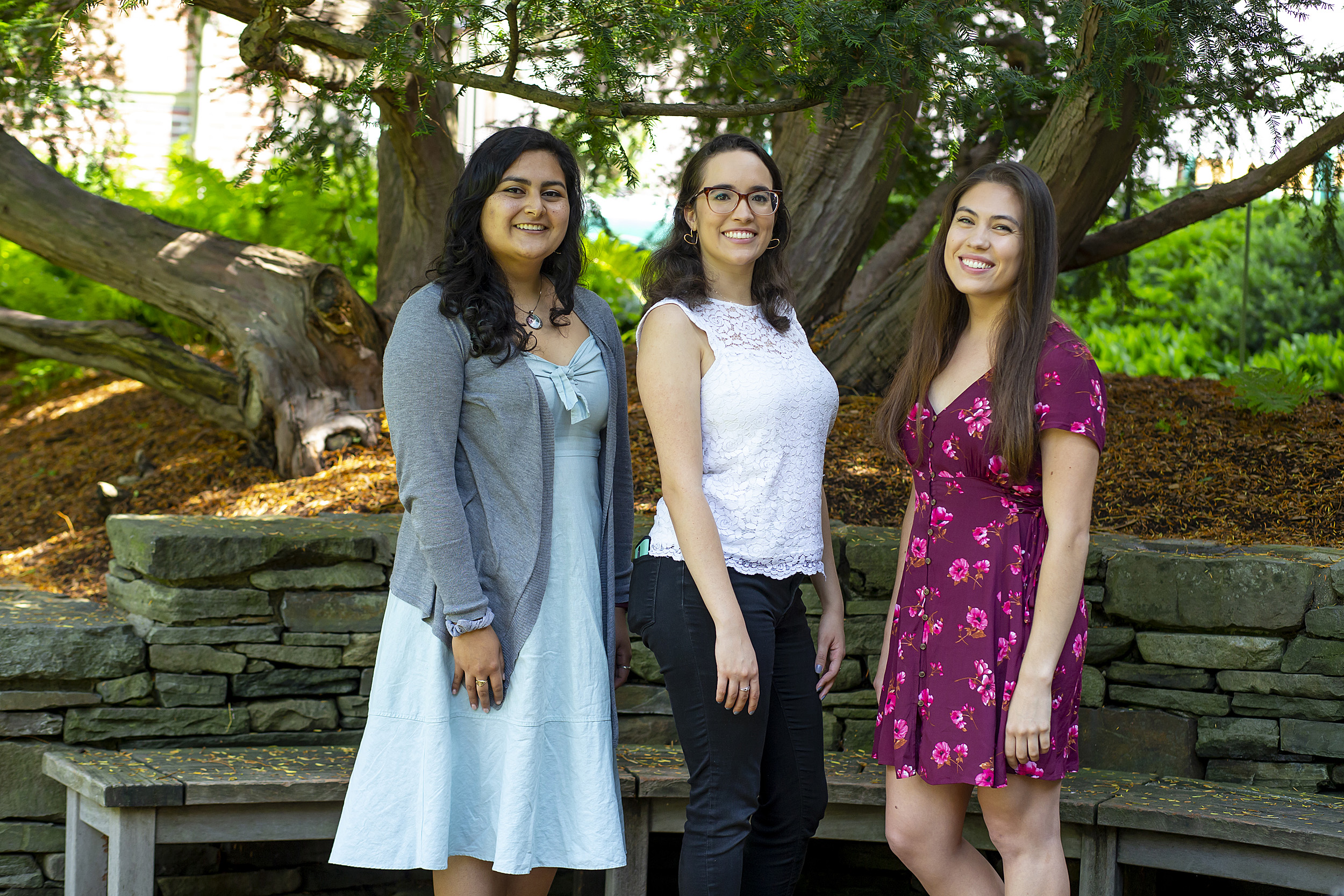

María Franco (from left), Tatiana Patiño, and Amanda Flores are part of the Harvard Teacher Fellows program.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

First-time teachers thrown into the COVID deep end

Fellows recall Zoom black boxes, shifting lessons, building ties with students, families

Novice teacher María Franco’s first day of in-person school was bittersweet. It took place in mid-May, not September, and only half the class was physically present, with the other half attending online. Still, after teaching online last fall and most of the spring, standing in a classroom at Chelsea High School for the first time filled her with joy.

“Having students in front of me has re-energized me and reminded me of why I wanted to teach in the first place,” said Franco ’20, who discovered a love for teaching in her senior year. “Teaching online was the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”

A member of the Harvard Teacher Fellows (HTF), a program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education that trains College seniors and graduates who want to pursue careers in the classroom, Franco and her cohort of 26 fellows found themselves launching their teaching careers amid the pandemic, forcing rapid adjustments all around.

The program, started in 2015, is typically five semesters, including a teaching residency in a partner school across the country. But with the spread of COVID it became four semesters of coursework with a one-year residency in a partner school in Greater Boston. And there were shifts in curriculum. Lessons on body language and behavior management were replaced by methods for remote instruction and ways to build meaningful relationships with students in the virtual world.

Fellows remained in Boston for their residencies for safety reasons, said Noah Heller, director of Harvard Teacher Fellows, and a lecturer in education. But having instructors and teachers-in-training concentrated in one geographic area also made it easier for the groups to work closely together and offer each other support as the classroom situation evolved in an unparalleled time.

For Tatiana Patiño ’20, who was inspired to become a teacher after taking USW35, a popular class taught by now-retired senior lecturer Katherine Merseth, the program’s support was key during last year’s turmoil.

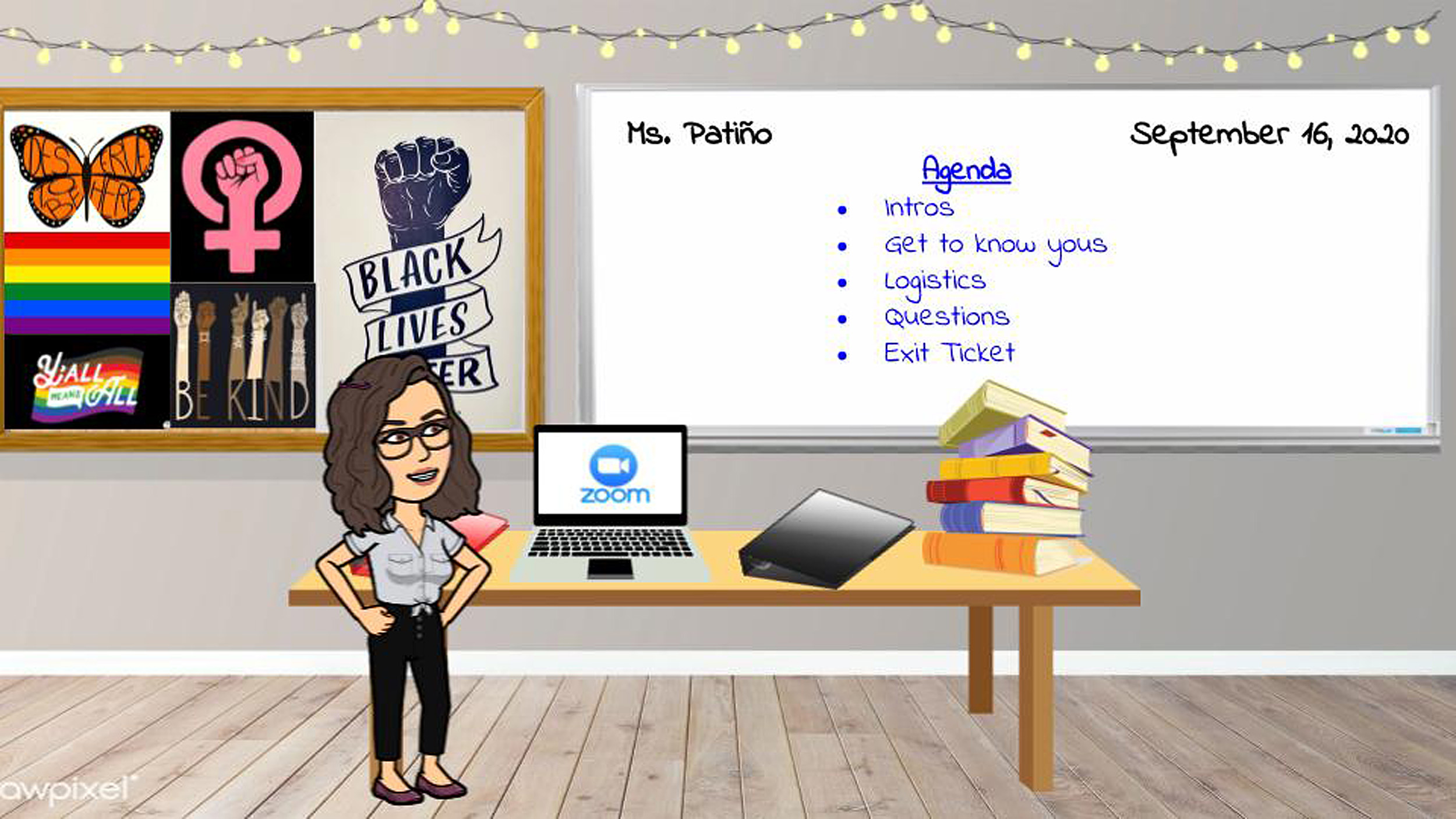

Tatiana Patiño’s online classroom.

Courtesy of Tatiana Patiño

“All our professors said, ‘We’re going to figure this out together,’” said Patiño, who taught ninth-graders at Chelsea High School as part of her residency. “They always asked us, ‘How can we help?’ ‘What do you need to feel supported?’ I can’t imagine teaching without HTF. It’s been the most incredible mentoring experience I’ve had.”

The challenges of teaching during COVID were many. The lack of physical proximity and the ubiquitous black screens on Zoom (in many areas students were not required to turn on their cameras) made it harder to connect with students. There were times when Patiño felt “like a YouTuber,” as if she were performing a monologue all day long. Franco thought she was “teaching into the void,” and found her online task more challenging than any of her classes at Harvard.

There were some upsides too. Online teaching eased newbie teachers’ anxieties about standing in front of the classroom and rendered moot several classroom-management challenges, allowing the fellows to focus on content teaching and pedagogical practices. The fact that many of the teachers-in-training were computer-literate and already familiar with Zoom and other learning platforms also helped smooth the shift to online instruction, said Heller.

“The playing field was much more equalized,” said Heller. “Often when you enter into teaching, you feel so far behind every other adult in the building, but everyone had their world turned upside down.”

In March 2020, when school buildings closed, the program quickly moved its own classes online and begin preparing students for remote instruction. When fellows started teaching in the fall, the familiarity they had with several online learning applications from their coursework made them feel more prepared than most teachers, who had to move online almost overnight.

The main challenge was connecting with students, said the fellows, who had to be creative and resourceful. Patiño started holding office hours in the style of college professors, and invited her students to her office to do homework or simply hang out. Many showed up and began to open up and turn on their cameras.

A native of Colombia who grew up in the suburbs of Atlanta, Patiño bonded with her students, many of whom were Latinx, by talking about quinceañeras, the Latinx equivalent of a Sweet 16 celebration, and by speaking Spanish, her self-described “superpower,” which helped her build relationships with her students’ parents.

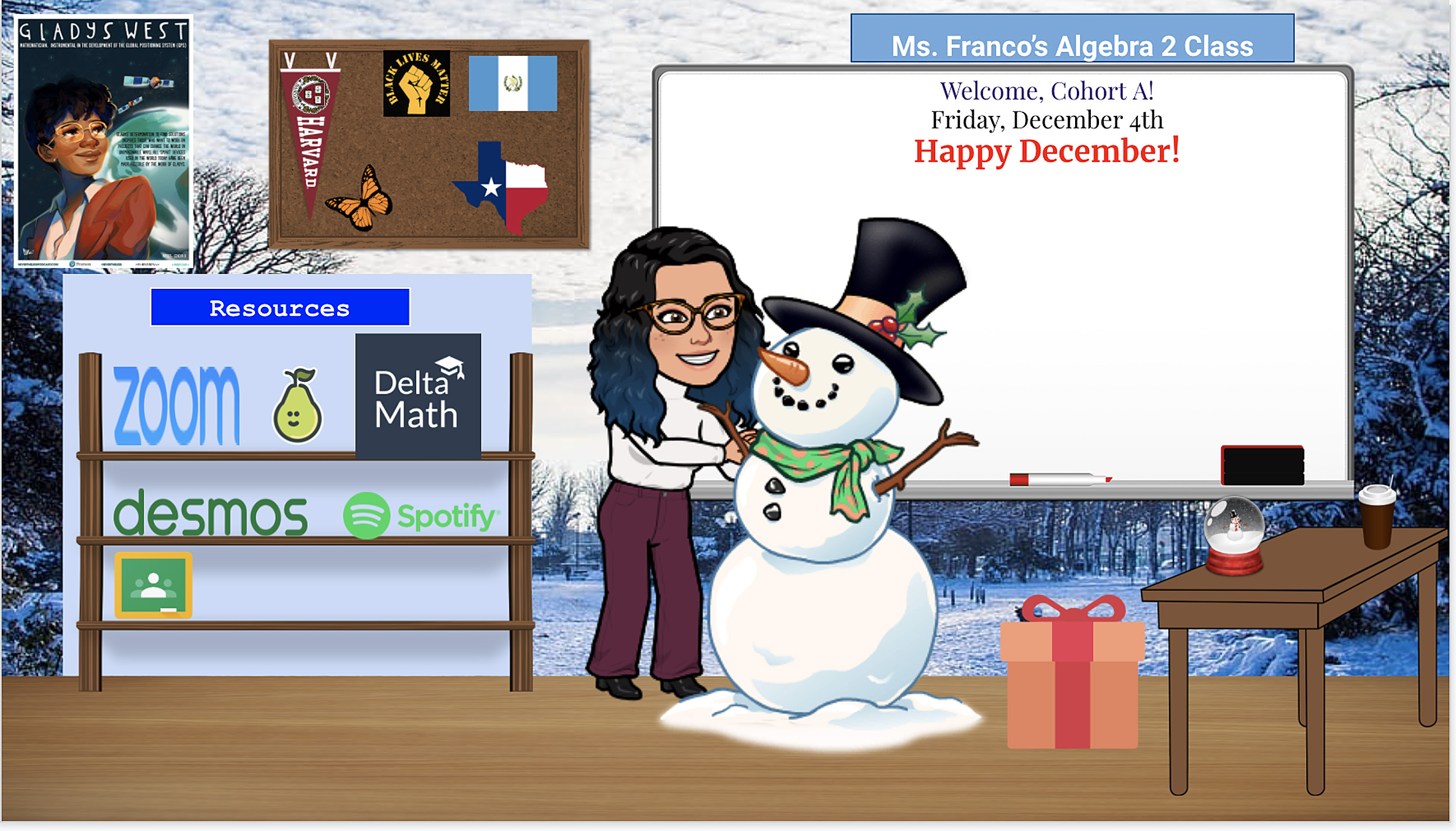

Franco — a Guatemala native who was raised in Dallas and was undocumented for 10 years — shared her personal story with her students hoping it would resonate with them. “When I was growing up, most of the kids were Latinxs or students of color, and most of the teachers were white,” said Franco. “It gives me hope that they’re able to see a teacher that looks like them and has gone through some similar life experiences.”

María Franco’s online classroom showcasing her heritage.

Courtesy of María Franco

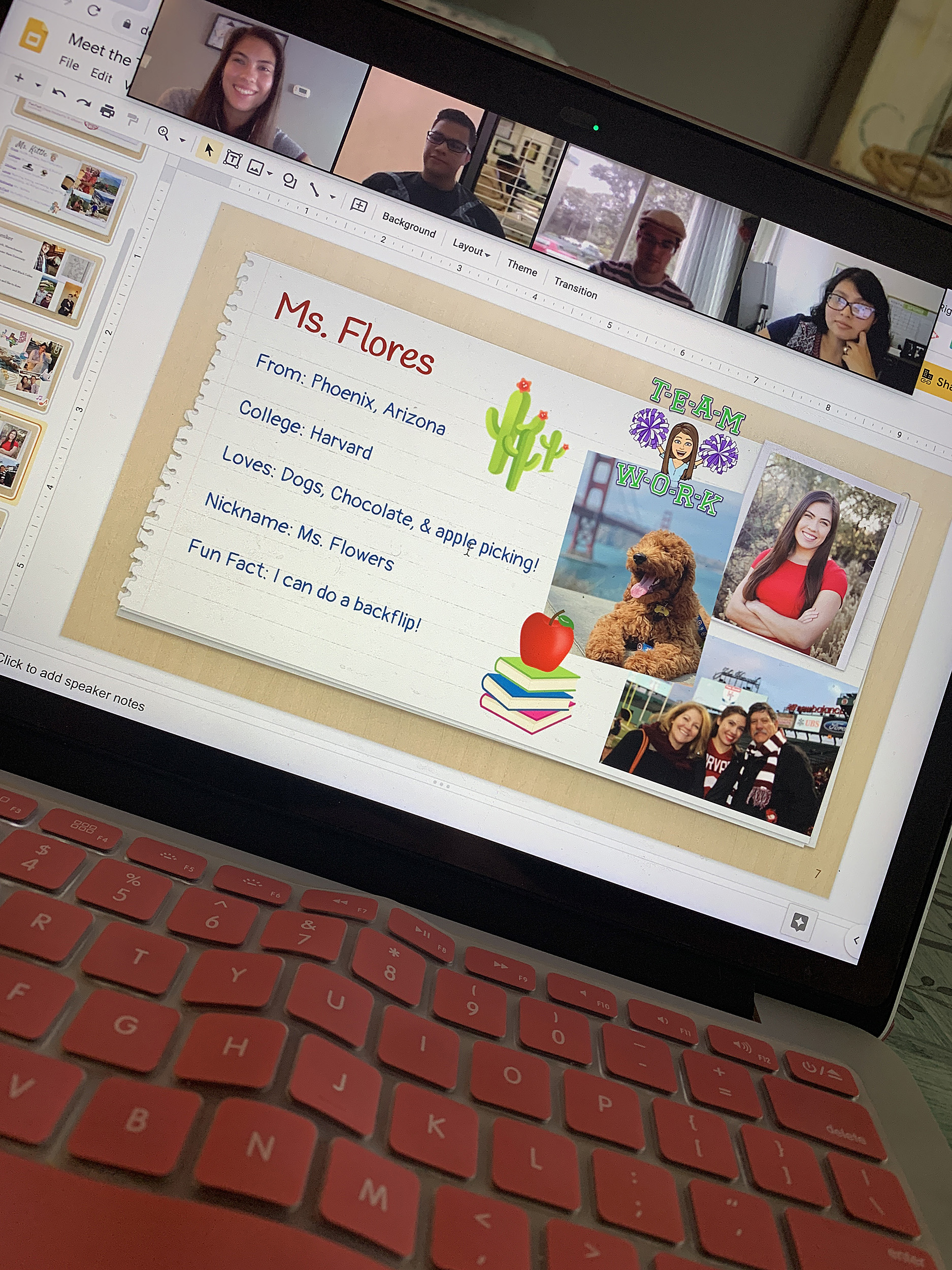

For her part, fellow Amanda Flores ’20 didn’t encounter many black screens in her Zoom sessions. She taught fifth-graders at Browne Middle School in Chelsea. At that age, students are not self-conscious and are excited about school, which Flores considered her “saving grace.” One of her hurdles was adapting her middle school lessons for fifth-graders (the program trains fellows to teach grades 6-12), but she relished every moment that students turned on their cameras to participate in class.

“There is a large battle trying to get the kids where they need to be, but there have been so many small victories along the way that kept me going,” said Flores, who would like to go back to her native Phoenix to teach. She plans to work in education policy in the future.

Heller said the pandemic provided many unique learning opportunities about how to be an effective teacher. And all the lessons go back to one of the program’s central philosophies: the value of forging relationships with students and their families. “Having students learning from diverse home environments has reinforced the idea of how important it is to get to know your students, to be able to relate to the contexts of their outside of-school lives, and to be able to facilitate social-emotional learning and the psycho-social supports needed for students and their families alongside meaningful and rigorous content,” he said.

Even though they all knew, in theory, the importance of establishing relationships with students and their families, the pandemic raised the stakes. Pandemic teaching and Zoom learning helped teachers in training see that students have a lot going on beyond the classroom.

Flores said she had thought she understood the importance of building personal ties. “But when you start, it doesn’t feel like that should be the main focus,” she said. “It feels that it should be, ‘We have to get better at reading. We have to learn the content.’ But this year showed us that isn’t going to happen unless we have strong relationships to fall back on, whether they’re on Zoom or the classroom.”

Amanda Flores going through an introductory slide for her students.

Courtesy of Amanda Flores

“It was a big wake-up call,” Patiño said.

With the pandemic in the rearview mirror, fellows are grateful they got to meet their students and teach in person for a few weeks before the school year ended in late June. Although they had to conduct hybrid classes, teaching to some students in the classroom and others online, and do more behavior management than on Zoom, they preferred that. If anything, they said, the pandemic strengthened their passion for teaching.

Next fall, Patiño will teach ninth-graders at Chelsea High School. Flores plans to go back to teaching after spending a year in Mexico City on a Fulbright Fellowship. The program’s retention rate is approximately 80 percent. It has 115 alumni. Last year’s cohort had 27 students, and this year’s cohort, the sixth, has 34.

HTF, for its part, continues its partnership with Chelsea Public Schools. Throughout July, each of the 34 fellows in Cohort 6 will be teaching in Chelsea’s summer school program as part of a revamped initiative to support learning amid the interruptions of the last two years. Instructional teams of four or more, composed of HTF fellows and a lead teacher from Chelsea, are working daily with students to help them master learning goals and make up credits needed toward graduation. This fall, 12 fellows will be teaching in Chelsea Public Schools for the teaching residency.

As for Franco, an economics concentrator who hadn’t considered a teaching career even though her mother and grandmother were educators, she will teach at Leadership Public Schools in Richmond, a long-time HTF partner school in the Bay Area of California. Teaching during the pandemic made her fall head over heels for high school students, who, in her words, are “funny, weird, and brilliant.”

“There are still days when my mom asks, ‘Why didn’t you go into consulting?’ ‘Why didn’t you go work for a bank?’” said Franco. “I tell her that if I had gone down those paths, I wouldn’t be happy right now.”