A pioneering geneticist and Renaissance man of parts

Richard Lewontin remembered as whip-smart, a fierce debater, and an engaged and loyal mentor and friend

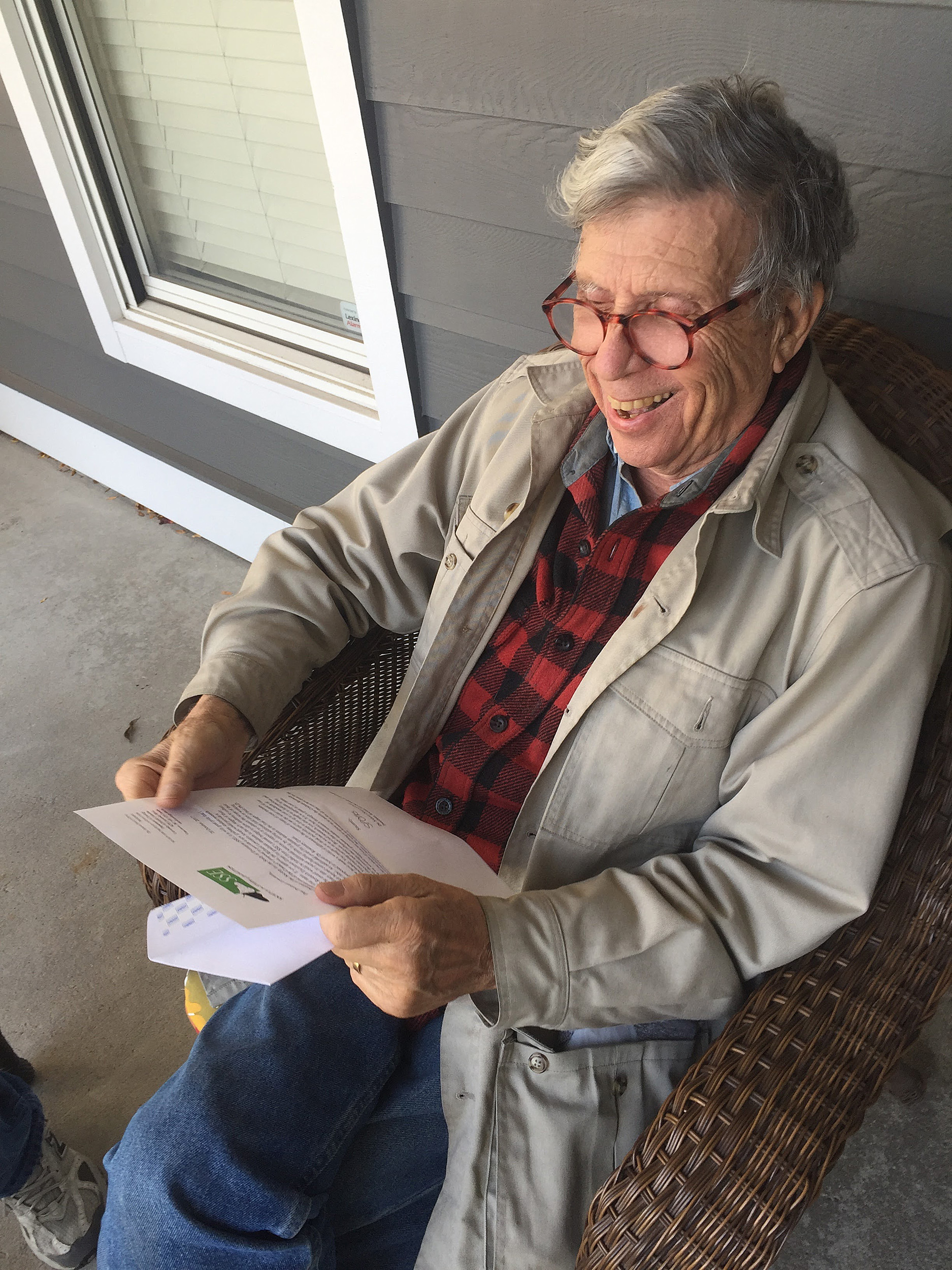

Dick Lewontin in 2017 with a letter from the president of the Society for the Study of Evolution, announcing the society’s intent to establish a Graduate Student Award in his honor.

Photos courtesy of Andrew Berry

A large wooden conference table stood beneath an enormous, mounted moose head in the center of the lab of renowned geneticist Richard “Dick” C. Lewontin. Many considered it nearly the beating heart of the lab, which took up the entire third floor of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Here students, postdocs, and visiting scientists gathered to dissect and debate an eclectic set of topics, from population genetics and ethics to politics and history.

“The table was the center of action. This was where the arguments were had,” said Andrew Berry, a Harvard lecturer in evolutionary biology. “His lab was the single most intellectually vibrant place in the universe because it was set up for interaction, drawing in all sorts of really smart, interesting people, often with different perspectives. It implicitly created an amazing sense of community.”

According to colleagues, friends, and former students of Lewontin, who died on July 4 in Cambridge at 92, this was the kind of environment in which the population geneticist and Renaissance man thrived. The space he created was not unlike himself, whip-smart, curious, and tough-minded yet warm and welcoming, capable of dealing out penetrating critiques during debates, but so engaging and magnetic that people, especially those passionate about all things science, gravitated toward him.

“It was a bit of a paradox: He was intimidating and brilliant and incisive, but he was also incredibly charismatic and loyal to his people,” said Berry, who served as a postdoctoral researcher in Lewontin’s lab in the 1990s. “He was truly a fantastic mentor, and he really went to bat for his people in a very Lewontin kind of way.”

A prime example was Lewontin’s refusal to put his name on scientific papers coming out of his lab if he contributed ideas but did none of the work, colleagues said. He also gave a nice corner office with large windows to the individual responsible for what was considered the least glamorous job in the lab — refreshing the food for the thousands of fruit fly larvae.

“It’s a big, dirty, messy, smelly job,” Berry recalled. “Lewontin said: ‘This is the worst job in the lab, so the person doing that should have the best space in the lab.’”

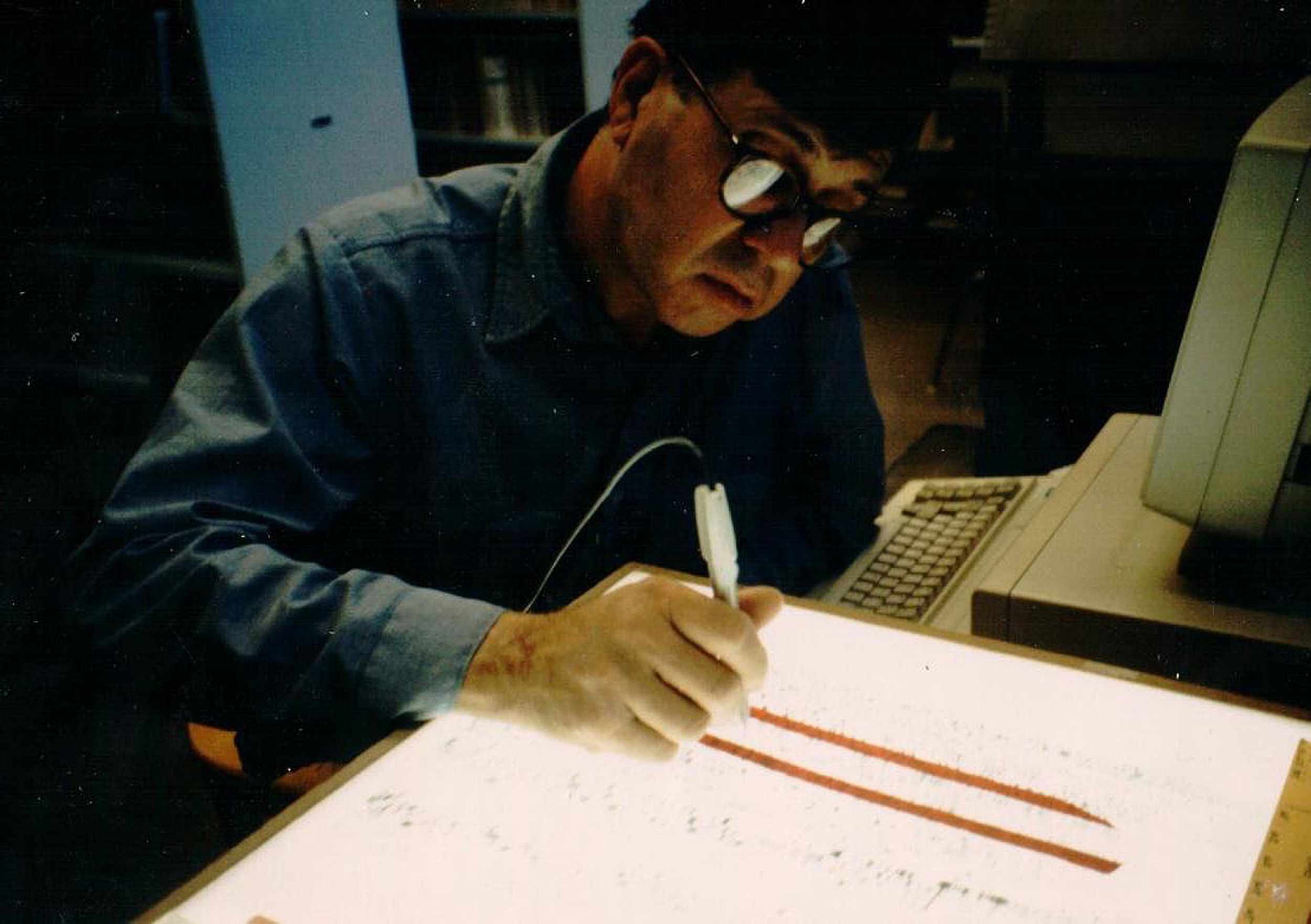

Lewontin working on a manual scoring DNA sequence.

Lewontin spent the majority of his career at Harvard, arriving in 1973 and holding one of the Alexander Agassiz Professorships until 1998. He retired in 2003.

He was familiar with Harvard before his appointment as a professor. Born in 1929 in New York City, Lewontin graduated from the College in 1951. He went on to do his master’s and doctorate work at Columbia University under geneticist and evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky.

Before returning to Cambridge, Lewontin taught and did research at North Carolina State University, the University of Rochester, and the University of Chicago, where he worked with biochemist Jack Hubby. He was known for embracing new technology and bringing innovative approaches from mathematics and molecular biology into his lab. His work studying genetic diversity within populations helped lay the foundation for the field of molecular evolution.

“Lewontin was a foundational scholar in the field of evolutionary genetics and evolution writ large whose impact on the field is hard to overestimate,” said Elena Kramer, Bussey Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and chair of the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. “His work has had a lasting impact on evolutionary biology and will continue to do so for generations to come through those he directly trained and indirectly inspired.”

In 1966, working with Hubby, Lewontin helped pioneer a method using gel electrophoresis to examine genetic diversity at the molecular level, revealing a surprising amount of genetic diversity among members of the same species.

Lewontin’s seminal work was a 1972 paper (later expanded into a book) that challenged the idea that genetic variation could explain differences among racial groups. His work showed that close to 90 percent of all human genetic variation could be found in one population and that differences attributable to race make up only a minor part of human genetic variability (about 15 percent).

“He was truly a fantastic mentor, and he really went to bat for his people in a very Lewontin kind of way.”

Andrew Berry, lecturer in evolutionary biology

He accrued a number of awards and honors during his career and authored a number of influential books, including “The Genetic Basis of Evolutionary Change” (1974), “Not In Our Genes” (1984), and “It Ain’t Necessarily So: The Dream of the Human Genome and Other Illusions” (2000).

Lewontin loved debate and often made his thoughts known through contributions to mainstream publications on topics in science or even economics and politics (he identified himself as a Marxist). His years-long back-and-forth with his Harvard colleague Edward O. Wilson, a founder of sociobiology who worked a floor above him in the MCZ, was especially famous and played out in many letters to The New York Review of Books.

While Lewontin loved intellectual rough-and-tumble, his many friends and colleagues also fondly recalled him as funny, caring, and deeply social.

Hopi E. Hoekstra, a professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and of Molecular and Cellular Biology, said she was struck by how much Lewontin loved to simply talk about science when she met him in 2007.

“He would just pop up and sit down in my office and just start talking about science and ideas he had and things he was thinking about,” Hoekstra said. “He would come to our lab meetings and just chime in, to all of our delight.”

As she got to know him better, she was struck by his curiosity outside of science, as well. She discovered he spoke many languages, played the clarinet, and was on the board of the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont, where he and his wife had lived since the 1960s, after he built a log cabin there. He was also a volunteer firefighter and would ask Hoekstra what he should do about the mice. Eventually, he started bringing them in to Hoekstra, who is also curator of mammalogy in MCZ, to add to the collection there.

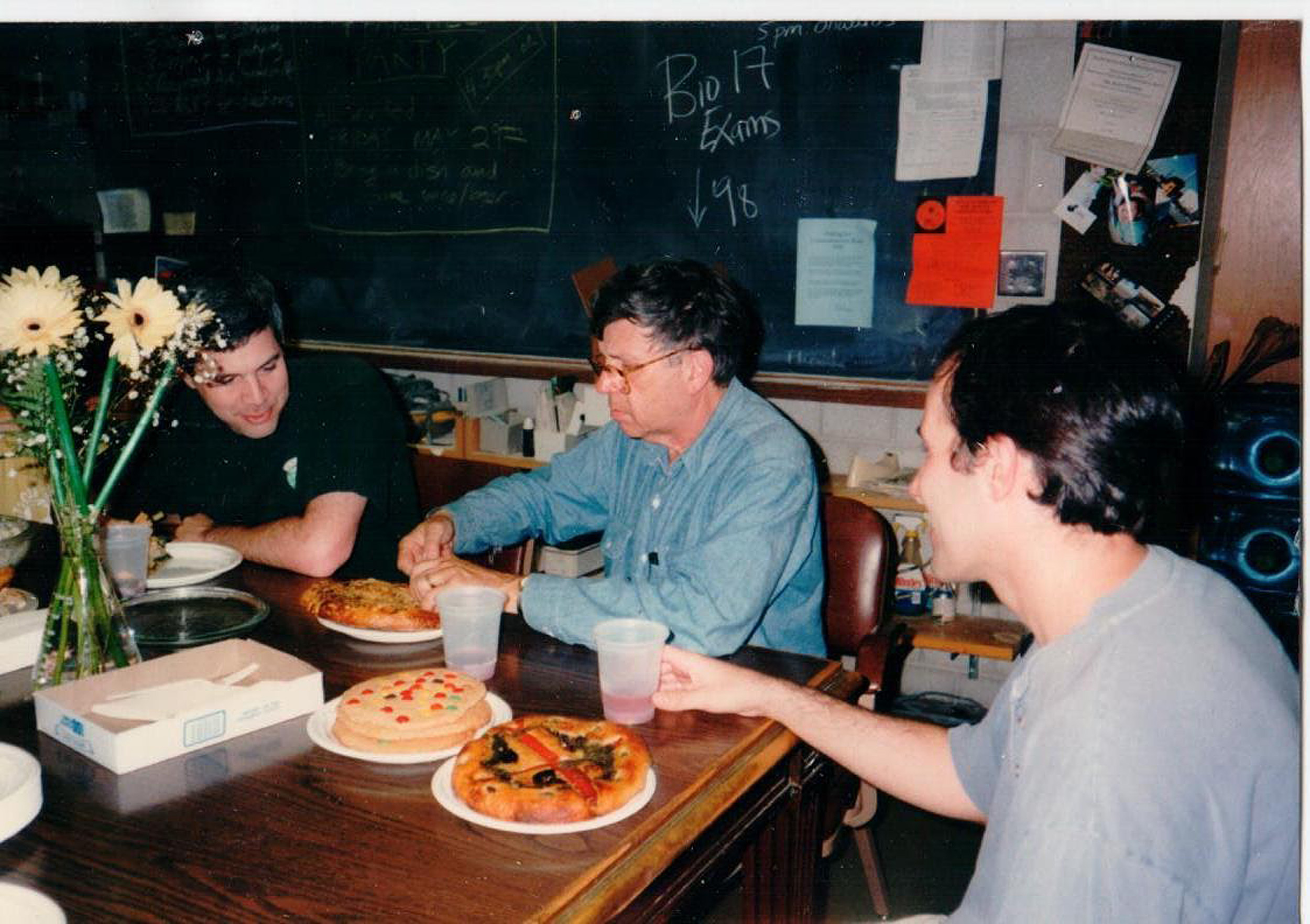

Lewontin (center) with Dan Weinreich, Ph.D. ’98, and Dmitri Petrov, Ph.D. ’97, at a central table in his research space.

“He had all of these wonderful interests,” Hoekstra said. “He was very deep in that sense.”

Scott V. Edwards, a professor in OEB who worked with Lewontin and received mentoring and thesis advice from him as an undergraduate, remembered that sense of curiosity, too.

“Normally, when he stopped outside my office to check his mail, I wanted to pick his brain about some abstruse population genetics theory, but he wanted to talk about birds,” said Edwards, an ornithologist. “He’d have questions about bird behavior and movements during migration. I would try to help him to figure out what species was coming through his bird feeder.”

Edwards also remembered how engaged Lewontin could become during class. He said the eminent professor, who showed up to teach each day in khaki pants, boots, and a work shirt, would become so engrossed in engaging with the class, through gesture and notes on the board, that he would end each session covered in chalk.

“He just always wanted to get to the core of the matter of whatever he was talking about,” Edwards said.

Lewontin is survived by four sons, seven grandchildren, and one great-granddaughter. Lewontin married Mary Jane Christianson, his high school sweetheart. They enjoyed more than 70 years together and died three days apart.