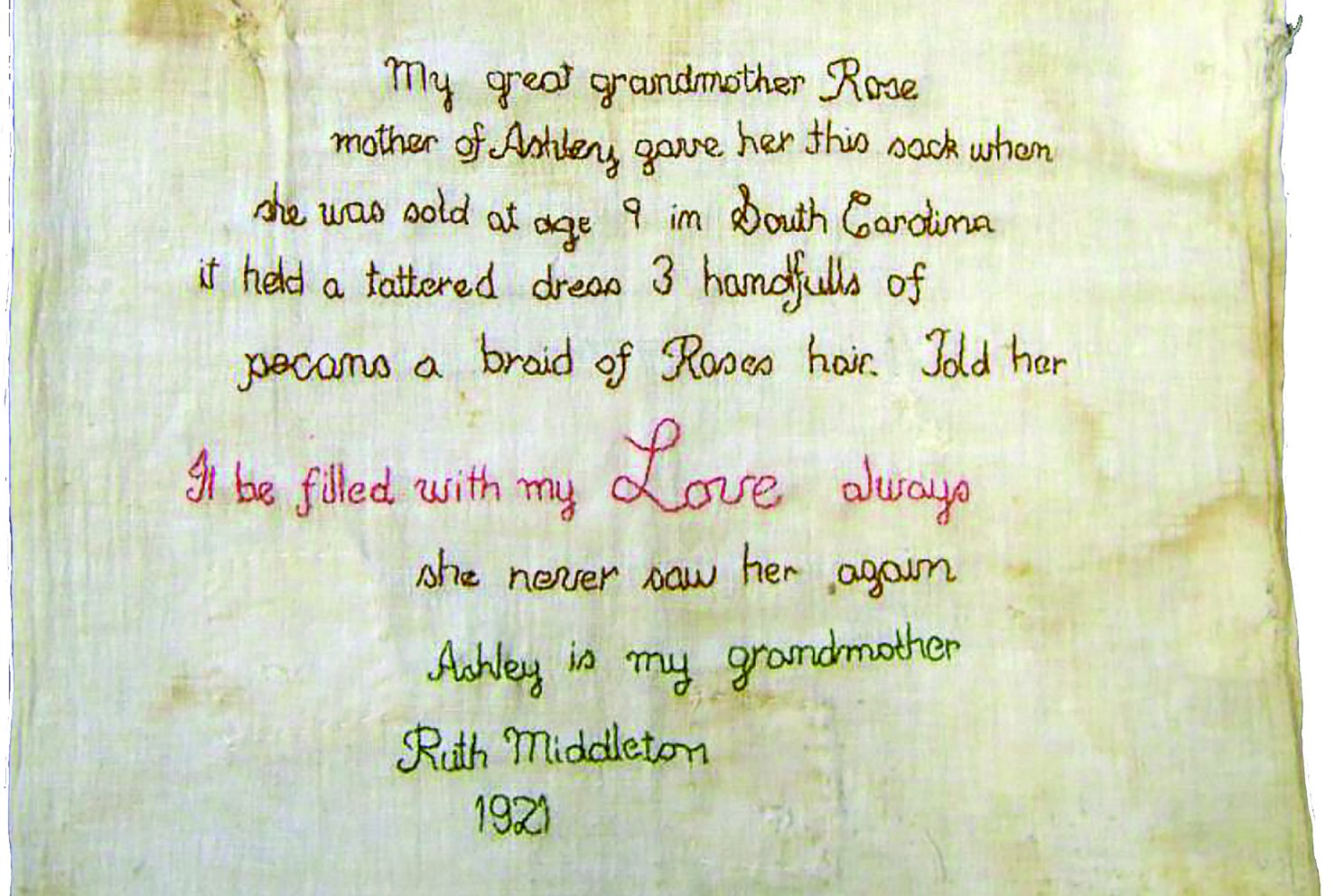

Ashley’s sack, embroidered with a piece of her family history.

Credit: Middleton Place Foundation

Her daughter about to be sold away, an enslaved mother carefully packs her a sack

Book explores a tattered artifact to piece together a history of a family torn apart

Editor’s Note: On Nov. 17, the Harvard historian Tiya Miles won the 2021 National Book Award in nonfiction for “All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake.” Below, the excerpt the Gazette published in June.

Excerpted from “All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake” by Tiya Miles, professor of history and Radcliffe Alumnae Professor. “All That She Carried” focuses on a worn, cotton bag given to a girl by her enslaved mother before the child’s imminent sale. The sack would re-emerge decades later, adorned with this embroidered family history: “My great grandmother Rose/ mother of Ashley gave her this sack when/ she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina/ it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of/ pecans a braid of Rose’s hair. Told her/ It be filled with my Love always/ she never saw her again/ Ashley is my grandmother/ Ruth Middleton/ 1921.”

When did Rose know that Robert Martin, the man who owned her and her daughter, Ashley, had breathed his last? Did a sense of dread descend on her in the Charlotte Street manor house when she learned of his death and then his burial in Magnolia Cemetery, a repository for the remains of many of Charleston’s elite residents?

Martin’s demise in 1852 from a condition described as “brain disease” would have grave consequences not only for his family but also for the Black families he and his wife, Milberry Martin, owned — families whose fate was tied up with the lives of their captors. When an enslaver died and his or her estate was reorganized, liquidated, or apportioned out to heirs, enslaved people suffered. They were made dead to one another through quick sales and forced separations that could lead to relocation deep within the cotton South. Wise to these realities, Rose would have wondered what fresh evils Martin’s passing portended for those she knew and loved.

Surely Rose had witnessed the “coffles” of forlorn men, women, and children, gliding like ghosts to and from the Old Exchange Building, an outdoor slave mall. These dark human trains of the shackled and surveilled moved across southern roads with increasing frequency in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s as cotton plantations spread westward. White men on horseback with whips and guns guarded the valuable cargo. Along the way, these middlemen of the domestic trade took sexual advantage of vulnerable girls and women and vended people to eager buyers at markets flying the customary red flag that advertised the peculiar nature of its merchandise.

A formerly enslaved man from Tennessee who had been sold four times across three states described the dreaded coffle: “We had to travel a good deal of the distance on foot. … The women, they put them in the wagon and carried them, but the men had to walk … and you could see the women crying about their babies and children they had left.”

Some unwilling migrants who came through Charleston, strangers to Rose from distant parts, would have lugged grimy “tow sacks” on backs welted like wounded trees. In the surge of forced migration that delivered tens of thousands from the Upper South and the coastal zone to the interior southwest stretching from Alabama to Missouri during the post-1820s cotton boom, enslaved people carried these rough-hewn bags to their next places of incarceration.

Is this how Rose seized upon the thought of the bag? Did she picture herself or Ashley marching in melancholy step to the sound of chains clinking across the Carolina swamps and pine forests? Or did Rose prepare her bundle weeks or months in advance, in expectation of emergency?

Here, in this country of grief where the danger of separation loomed so large, we can imagine that residents always kept a bag packed, whether physically or psychically. When Rose prepped an emergency kit for her daughter, she packed for persistence in the face of “incapacitating uncertainty,” to borrow a phrase from the Civil War historian Drew Gilpin Faust. Rose would have known this state of instability as the only constant in her life. Yet she found the inner strength to meet a measureless threat with action.

What we know from the account sewn on the sack by Rose’s descendant is that Rose responded to this crisis with practicality and purpose. She gathered a variety of items to provide for her daughter’s basic needs. By sustaining her daughter’s life in the present, she forged a pathway for Ashley’s survival. And setting her daughter down that path was a projection of continuation. In packing the sack, Rose not only rescued a single child, but also ensured the persistence of a family.

It is rare that we get to peer inside one of the hastily prepared bundles that sold or escaping enslaved people grasped in times of sudden change. Each item Rose packed for so significant a parting was both essential and versatile. The tattered dress could protect a body from exposure and shield an enslaved girl’s inner dignity. The dress Rose packed also had another potential function, as fabric stored wealth, especially for women, who used cloth as currency or a trade good. Although Rose seems to have packed a shredded dress most valuable for its personal meaning, she certainly would have recognized that Ashley could repurpose the fabric or trade it. Rose also packed pecans, a concentrated energy source and a specialty food in the 1850s Lowcountry that Ashley could have eaten to stave off hunger or bartered for another necessity. Finally Rose tucked a lock of her own hair into the bag, the most unusual element of her care package. While hair seems at first a whimsy in an emergency bag such as this, it may be the most potent item, symbolically and even spiritually.

Rose may have understood her movements to matter on more than one plane of being. Just as she drew on inner strength to withstand this trauma, she may have called on spiritual help to sanctify her emergency pack. Extrapolating from interviews with Black residents of coastal South Carolina and Georgia, the anthropologist Mark Auslander, who has worked closely with the sack, has suggested that Rose’s packing instantiated a spiritual ritual, given that the bag resembled “regional medicinal bundles.” And Rose, he has indicated, quoting contemporary interviewees, may have been “doing something with, a blessing, something sacred.” In this interpretation, the sack, once packed, became animated with a protective spirit through Rose’s ministrations and, especially, through the lock of her hair.

A reading of the sack as a protective spirit bag would suggest that a braid of Rose’s hair was meant to enliven it with Rose’s spirit. Certainly, the braid must have been meant to capture and concretize a tactile memory of Rose for her daughter, functioning like a snapshot that Ashley could hold in her hands. By giving a gift that had once been a part of her own body, Rose also bestowed a potent reminder of her presence in Ashley’s life. For hair could function as a token of memory and social connection across the distances the slave trade created. Through the medium of her braid, Rose may have wanted to synthesize nearness and convey to her daughter a lasting memory of their emotional connection.

So when did Rose know?

We must presume Rose always knew that she would birth a motherless child. Since the inauguration of the transatlantic slave trade in the late 1400s, through the acceleration of the American domestic slave trade in the early 1800s, and still today, Africans and people of African descent have borne a crisis of mother loss. Memoirist and cultural theorist Saidiya Hartman captured this profound historical state when she traveled to Ghana in search of her African roots. Her numbing insight arrived at on the journey became the organizing idea of a breathtaking travel narrative. “Lose your mother,” Hartman found in her book of the same title, was the forced imperative of the slave trade and a raw truth of African American experience.

We are a people suffering from the loss of a motherland, a mother tongue, and a mother’s knowledge of our new names. It might even be said that the search for true belonging and the quest for relational repair lie deep at the heart of the modern Black psyche. In the face of devastating mother loss, our ancestors’ answer was mother love: a graspingly fierce, imperfect insistence on making and tending generations. An affirmation of Black life embedded in love and stashed in a sack is, after all, what Rose was packing for.

Copyright © 2021 by Tiya Miles. Excerpted by permission of Random House, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.