iStock

Is inflation a problem now? Maybe, but more likely not

Surge in consumer prices is likely temporary and due to rising demand, supply problems, business professor says

If you’ve tried to buy just about anything from groceries to airline tickets lately, it’s no surprise that prices are on the rise. But many analysts were taken aback when the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its Consumer Price Index (CPI) earlier this week showing prices jumped 4.2 percent in April over a year ago, a much sharper spike than the 3.6 percent economists expected.

Even when staples like food and energy, commodities that fluctuate in price month to month, were taken out of the CPI equation, prices are up 3 percent since 2020 and rose 0.9 percent just between March and April, something that hasn’t occurred since 1982. Price hikes and dips are a routine fact of free market economies. But when they rise abruptly or approach levels that hinder consumer spending, inflation can trigger all sorts of knock-on effects, which could spell trouble for the U.S. economic recovery.

Alberto F. Cavallo, Ph.D. ’10, Edgerley Family Associate Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, studies the macroeconomic policy and measurement implications of price fluctuations in economies around the world. Since early 2020, he’s been focused on how COVID has affected consumer prices, drawing on spending data from Opportunity Insights, a research initiative run by Harvard economist Raj Chetty. Cavallo spoke with the Gazette about what’s driving prices up, how far they may still go, and what COVID has revealed about the U.S. economy.

Q&A

Alberto F. Cavallo

GAZETTE: In March 2020, at the very onset of the pandemic, you argued that consumers were experiencing a higher rate of inflation than the CPI was capturing. So is this 4.2 percent rate increase since April 2020 genuinely new and surprising, as many have suggested? And why are prices rising sharply when demand is up and many industries seem to have adapted to COVID?

CAVALLO: Since last year, I’ve been investigating this issue of the measurement of inflation during COVID. COVID dramatically changed the way we did our spending, during the lockdowns in particular. The CPI is constructed in a way that the weights assigned to each category of consumption are not updated often. During 2020, we were still using the weights assigned in 2019, and that meant [it] did not correctly reflect the actual experience of higher inflation people had through March of 2020. But that was a temporary measurement problem. The weights were updated in December of 2020.

It’s not a new thing that happened in the last couple of months, as the official statistics reflect. Some people, particularly low-income people, have actually experienced higher levels of inflation for several months. Food inflation has been particularly high during COVID, and traditionally, low-income households spend relatively more on food.

Why are we seeing more inflation right now? There are basically three factors. One is the so-called “base effects.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates an annual inflation rate [by] compar[ing] prices today to prices 12 months ago. Twelve months ago, we were in the middle of the crisis; prices were falling. In the official CPI, they were particularly low, so the annual inflation rate appears higher right now. That probably increases the annual inflation rate by roughly one percentage point. If we didn’t have that, we would be closer to three percent. Still, that’s a temporary effect. It’s not the whole story.

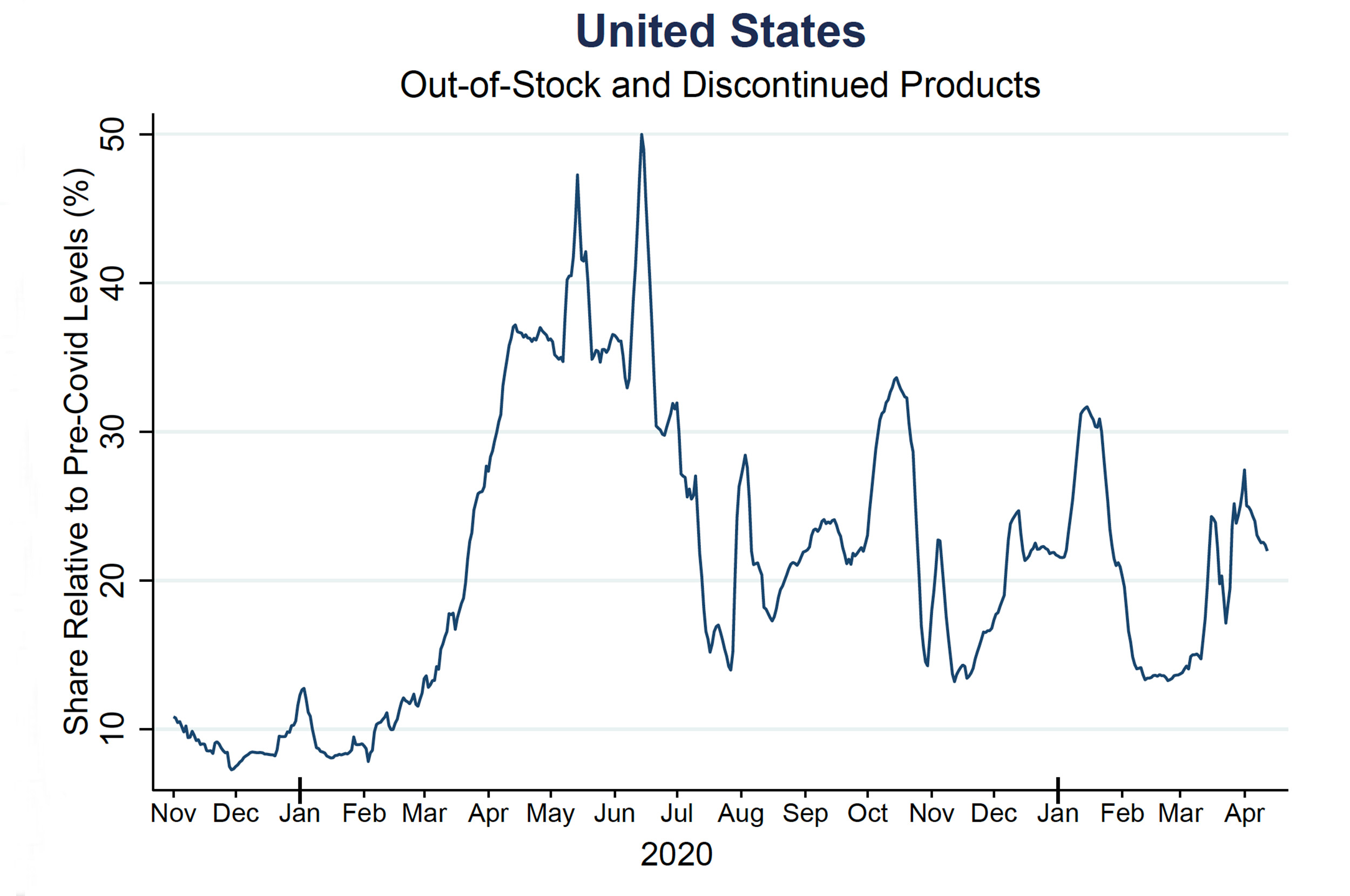

[Consumers] are seeing more inflation right now because of two other factors: supply disruptions and demand, which is picking up. No one can actually measure supply disruptions at the retail level, so we have been monitoring the number of “stock outs” online at large retailers. We built these time series that measure temporary stock outs, which are when the website shows “this item is out of stock,” but it’s supposed to be coming back. And then, we are measuring what we call permanent “stock outs,” which is when the item completely disappears from the stores. What we find is that we had a spike in temporary stock outs in April of 2020. The temporary stock outs went from about 15 percent of all items in the store, which is the normal level we were seeing before the pandemic, to over 25 percent. And then there was a gradual decline over time. We seem to be going back to normal in terms of how many of these items are temporarily out of stock. But what is surprising is how many items have disappeared from [retailers’] websites altogether. They’re not even offered for sale. The total number of products or varieties of products have fallen by about 20 percent relative to what we saw pre-pandemic. The Fed has emphasized that they expect the supply disruptions to stop putting upward pressure on prices in the next few months. They’re proving more persistent than many people expected, me included. As soon as vaccinations started, I thought [there’d be] faster recovery in some of the supply disruptions. I expect now, based on the research we have done, that they will continue having an impact for at least one quarter more or even longer. I do expect them to eventually dissipate or improve towards the end of the year.

The final factor is demand, which is recovering very quickly. Nobody knows what will happen with demand in the future. It will depend a lot on how the Fed and also the Treasury react to higher levels of inflation, if it persists toward the end of this year.

GAZETTE: Prices for certain categories of goods that went up at the onset of the pandemic (real estate, food, energy, construction materials and services, large appliances, home furnishings, automobiles) remain high, while those categories that nosedived early on (air travel, hotels, restaurants, and live entertainment) are rebounding pretty significantly. Why are prices up across so many different sectors?

CAVALLO: At the beginning of the pandemic, we had competing forces. We had some sectors that were experiencing more demand temporarily because of the lockdowns and some sectors where demand was collapsing — hotels, transportation — all those prices were falling. There were also some sectors experiencing supply disruptions. You had supply pushing prices up, and demand pushing it down and so, prices were, if you will, contained.

Many firms are operating still with a lot of additional costs. Think of restaurants, for example. They can accept new customers, but many restrictions of social distancing still remain. They can occupy only half of their tables. They’ve been having these higher costs ever since we have been able to go back to restaurants, and demand is picking up. At the same time they’re still facing some of the supply disruptions. So all of these forces are coming together and pushing prices up. That’s what’s special about this moment we’re living right now: We have supply disruptions; we have demand pushing prices up; and we have some of these temporary base effects, creating the impression that inflation has been rising very quickly — in part because of what’s happened in the last few months, but also, because we’re comparing [it] to a very depressed price level back [in 2020].

“Some people, particularly low-income people, have actually experienced higher levels of inflation for several months. Food inflation has been particularly high during COVID, and traditionally, low-income households spend relatively more on food,” says Alberto F. Cavallo.

Photo by Stu Rosner

GAZETTE: What does the CPI and other data say about the U.S. economy and where things are heading?

CAVALLO: It’s important to keep an eye on inflation. The main variables that macroeconomists look at are inflation, output, and unemployment. Low levels of inflation, particularly after a recession like we experienced, can be seen as a positive sign that the economy is recovering, and demand is picking up. It becomes worrisome when the inflation level continues to rise beyond the target of the Fed, which would be slightly above 2 percent in the next few months. It takes a long time, however, for inflation to become endemic in an economy. I’m originally from Argentina, a country that has a long history of inflation. For many years, governments introduced extremely expansionary policies that eventually led inflation to levels beyond 10 percent and eventually to hyperinflation. But I don’t see that playing out in the U.S. I believe that if inflation were to rise to levels that economists consider alarming that the Fed will react responsively and try to pull down the economy.

GAZETTE: What does the Fed consider alarming?

CAVALLO: Initially, it was 2 percent. Now, they say they want an average of 2 percent. Given that we have experienced levels of inflation that were below the target for a while, we can expect them to allow inflation to rise to 3, maybe 4 percent. Most people would expect that if inflation remains above 4 percent for several months, then we are likely to see the Fed becoming more worried about inflation.

GAZETTE: How do politics and policy factor into such decisions?

CAVALLO: There are two main policies, monetary and fiscal. The Fed has control over the monetary policy. The Treasury and the Biden administration controls the fiscal side. They’ve certainly announced a very big stimulus to try to get the economy to recover. Some economists believe the magnitude of the fiscal expansion is too big. Others believe it is right and that we shouldn’t worry. That decision will eventually depend on how the statistics of unemployment and output are comparing to inflation. And while inflation remains relatively low, or there’s the perception that inflation is still a level that can be controlled, then I think policy, both on the Fed side and the Treasury side, will still favor stimulating output and making sure we can get the economy to recover.

GAZETTE: How should businesses and economic analysts use the recent trends in consumer spending to learn from and/or plan for the next crisis or is COVID simply a sui generis event?

CAVALLO: COVID is a very particular crisis. It’s so complex. It has all these different characteristics — supply, demand; it’s a global event where everybody is affected; there was a financial panic at the beginning that was resolved; and then we have a health crisis. I use it to teach my students all these different channels that can affect the macroeconomy. I think we can learn a lot from that.

On the topic of inflation, COVID led me through some important lessons. One is, sometimes we need better data to know what’s really happening. I do most of my work trying to create more high frequency indicators, so we don’t have to wait too long to see what’s really happening in the economy. I think it’s going to give a push to the use of better data in macroeconomics. In a way, it’s a positive thing that may come out of all this.

There’s been talk about big data helping policymakers for a long time. Statistical agencies, which produce the official indices like the CPI, have been very reluctant to use these new data sources. But COVID forced them to. For example, on the collection of prices for the CPI, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has traditionally sent an army of people to stores to write down the prices of products they see. And I’ve been telling them for over 10 years that, for some categories of goods, you can go online and find exactly the same prices you find in the store. COVID shut down their offline operation, so they moved online. And that I think has increased the capabilities of some of these statistical agencies. That’s just one example — collection online.

Many of them, for example, are considering collecting data on consumer spending thanks to the work that Opportunity Insights has done in showing that credit cards and debit card information can be tremendously useful to monitor very quickly what’s happening with the spending patterns of different consumers. So I think there’s a lot of, not just potential but actual improvements during COVID in the measurement of macroeconomic variables that is going to be a quite helpful for policymakers, if we ever faced another crisis like this. Hopefully, we won’t.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.