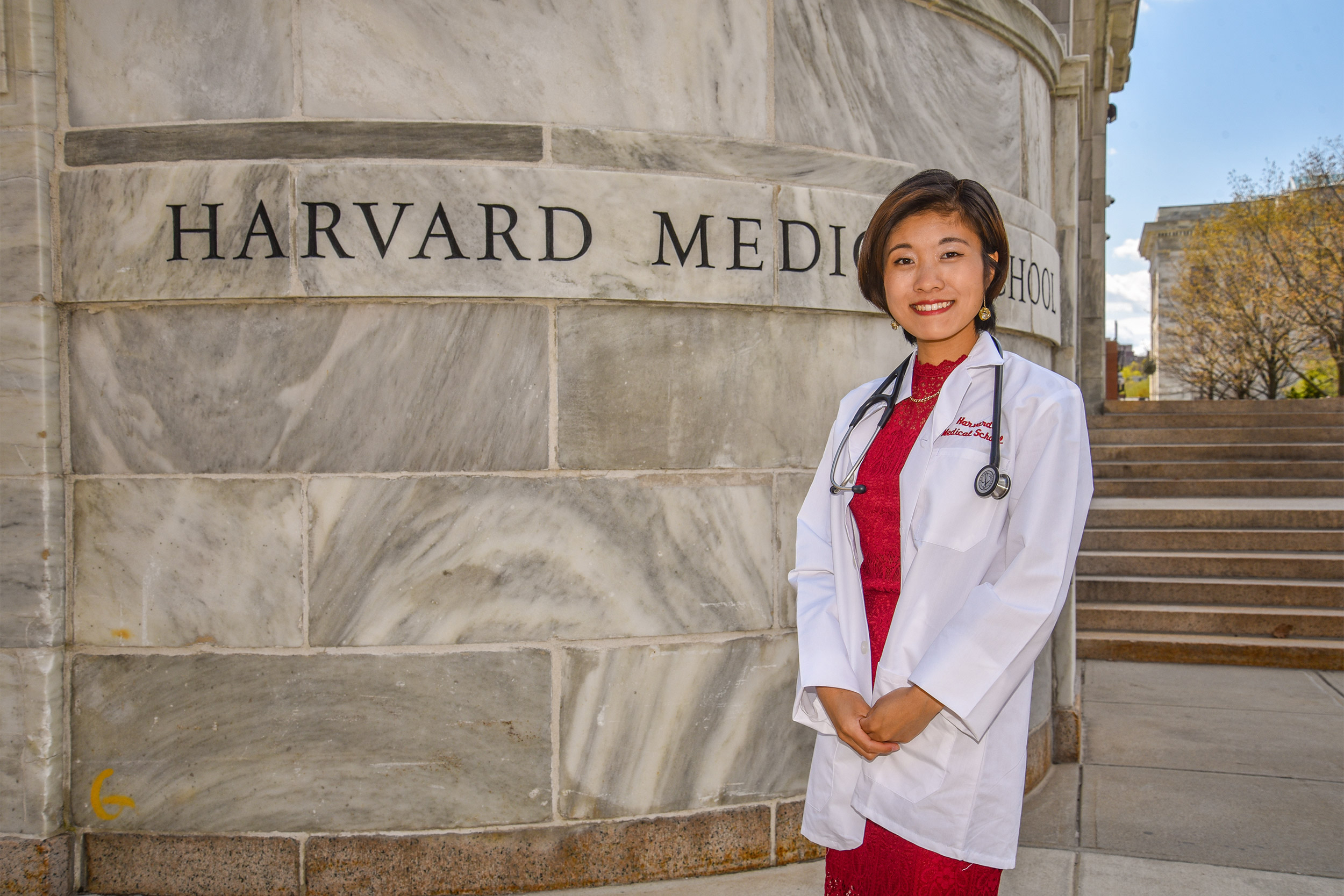

Ryoko Hamaguchi is graduating this year from Harvard Medical School and will train in the Harvard Plastic Surgery Residency program.

Photo by Steve Lipofsky

Creating a niche

M.D. student Ryoko Hamaguchi connects art, medicine, cultures

This is one in a series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

Every week during her first year at Harvard Medical School (HMS), Ryoko Hamaguchi sat in the front row of her preclinical classes sketching a portrait of a guest patient on her iPad.

“I would incorporate elements of their story as they were telling them,” said Hamaguchi, who is graduating this year and will train in the Harvard Plastic Surgery Residency program.

The patients were brought into the class because they each had an illness or health condition that was connected to that week’s preclinical curriculum.

Later, when the students were discussing the patients’ cases, the digital portraits were a way for Hamaguchi and her classmates to share “reflections about what we had heard and how we were connecting the science that we were learning with the human aspects of illness.”

Bridging art and medicine

“My mom has always said that the first skill I learned was to draw,” said Hamaguchi, recalling that she was constantly doodling as a child.

It wasn’t until she participated in an interdisciplinary arts undergraduate honors program at Stanford, where she was a biology major, that she brought her love for art and her interest in science together.

“That was the first time that I explored the field of medical illustration,” she said.

The drawings she completed for the program’s thesis project ranged from “artistic depictions of human anatomy” to portraits of organ donor recipients paired with the donors, based on photos provided by the donor’s family. The aim was to capture “the poignant human relationships” that can sometimes happen when a donation recipient and a donor family connect.

The artwork for that project, which she published in a book, was the first step Hamaguchi took toward carving out a future combining art and medicine. “That was something that I didn’t really expect to be able to do,” she said, since she had never pursued formal art training.

At HMS, Hamaguchi said she received encouragement before she was even admitted.

“By some stroke of luck,” she said, she was paired with Rafael Campo, HMS associate professor of medicine, part-time, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, for her admissions interview.

“It was an instant connection,” Hamaguchi said.

She carried a huge black art folder with samples of her work to all her med school interviews, including the one she had with Campo. When she laid out the artwork in her portfolio in his office, she said it resembled more of “an art critique session than an interview.”

What Hamaguchi remembers most, and what struck her as different from the interviews she had at other schools, was Campo’s encouraging her interest in “exploring the intersection between art and medicine.”

She said it impressed her because it was coming from someone “who has done that masterfully in the realm of poetry.”

The interview with Campo set the tone for Hamaguchi’s first experience at HMS, and when she arrived at the School as a student, other faculty, including Dean for Medical Education Edward Hundert and Dean for Students Fidencio Saldaña, continued to encourage and support her artwork.

Growing up in the U.S., Ryoko Hamaguchi said she was raised in “a culturally and linguistically Japanese traditional family.”

Photo by Steve Lipofsky

Bridging two cultures

Hamaguchi was born in Japan and came to the U.S. when she was 6. Describing her upbringing in a “a culturally and linguistically Japanese traditional family,” she said that at home they spoke only Japanese, and she and her brother, who was born in the U.S., attended a Japanese school on Saturdays, studying the language, history, and culture of their homeland with the same textbooks and curriculum used by public schools in Japan.

Spending her weekends studying “was not the most enjoyable thing growing up,” she admitted, but now she is grateful for that connection to Japanese culture and appreciates her parents’ “determination for us to preserve our Japanese identity.”

Even though Hamaguchi said she has encountered few Japanese-speaking students at HMS, she has managed to find other ways to stay connected with her culture. As part of the Japan America Academic Center, Hamaguchi has given tours of HMS to middle and high school students from Japan.

Right now the tours are virtual, but before the coronavirus pandemic, she guided students in person, giving them tours of TMEC and a simulation lab at Beth Israel Deaconess.

Through connections with the Japanese community at Harvard Business School, Hamaguchi applied and was selected to serve as a national delegate for Japan at the Y20 Summit 2020. She spoke at the online summit in October 2020. The Y20 Summit is an international youth conference held in advance of the G20 Summit that gives a voice to young people from G20 countries, allowing them to discuss and debate issues and contribute solutions to global challenges.

As a delegate from the U.S. representing Japan, she was able to meet and work with the other delegates from Japan. The delegates connected with each other and with Japanese students and young working professionals via webinars to “hear what their life is like, what their concerns are, particularly during COVID-19,” Hamaguchi said. “I feel like we were able to deliver that to the G20 leadership.”

A transnational role in the pandemic

As the world has struggled with the pandemic, Atul Gawande, the Samuel O. Their Professor of Surgery, at HMS and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, began researching the global responses of various countries through his research group, Ariadne Labs.

Gawande reached out to HMS students for assistance and Hamaguchi volunteered in response to his call for a Japanese-speaking student.

Hamaguchi was then paired with volunteer physician-researchers, many of whom were Japanese, at Brigham and Women’s and Massachusetts General Hospital. They were working with physicians in Japan to find out how they were dealing with the pandemic, initially focusing on the country’s efforts to limit health care provider exposures and infections.

Harnessing the bilingualism and connections of this international group, Hamaguchi said, “we were able to have very rich conversations with the health care providers” in Japan and uncover underreported nuances of the Japanese public health system and their implications for the COVID-19 pandemic.

She enjoyed being able to “be a bridge between Japan and the U.S., the two countries I call home.”

Ultimately, she became the project lead and described the experience as a “big learning opportunity” to find out how the health care system was challenged by and evolved through the pandemic in Japan.

A research trifecta

Adding a fifth year to her M.D. program, Hamaguchi has engaged in interdisciplinary research projects in wound healing, grappling with the topic through the lenses of translational, clinical, and basic science investigation.

During her third year, Hamaguchi got connected with her primary mentor, Dennis Orgill, HMS professor of surgery and medical director of the Wound Care Center at Brigham and Women’s. She was able to work in a plastic surgery research lab there.

Using mouse models, the team studied new therapeutics and treatments for diabetes with a goal of translating the findings into improvements in care for patients with debilitating wounds, such as burns or diabetic foot ulcers.

Hamaguchi also worked with Orgill on a clinical retrospective study on reconstructive plastic surgery treatments for a chronic, painful skin condition, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Because of her foundation in biology, Hamaguchi also wanted to delve into the basic science of wound healing so she took a position in the lab of George Murphy, HMS professor of pathology and director of dermatopathology at Brigham and Women’s.

Hamaguchi led a project using 3D printing and bioprinting technologies to recapitulate the architecture of the human skin stem cell niche. This work evolved into her honors thesis, and she presented her findings at the 2020 Soma Weiss Student Research Day at HMS, the International Society for Stem Cell Research annual conference, and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute’s annual retreat where, as the only medical student among the oral presenters, she received the Best Trainee Presentation Award.

Beyond the contributions of this project in basic skin biology, she is excited by how this work may open new doors toward increasingly sophisticated models of skin diseases, as well as advanced engineering of skin substitutes for use in clinical applications for burns and acute and chronic wounds.

One day, she said, plastic surgeons might be able to take biomimetic synthetic skin “off the shelf in the operating room” and apply it to burns or other nonhealing wounds, not only avoiding skin grafts but potentially enhancing healing through engineered skin that looks and behaves like natural skin — complete with microscopic structures such as hair follicles and stem cell niches.

“That could change many things that we do in plastic surgery,” Hamaguchi said.

A burgeoning career as a medical illustrator

Even though there wasn’t much time for sketching patients during her clinical rotations, Hamaguchi “made it a practice to … use my artistic talents in some way” during each rotation, whether it be creating illustrated one-page summaries on clinical topics or sketching memorable surgical cases from memory. She said showcasing her work helped her develop a network of faculty and residents who believed in her.

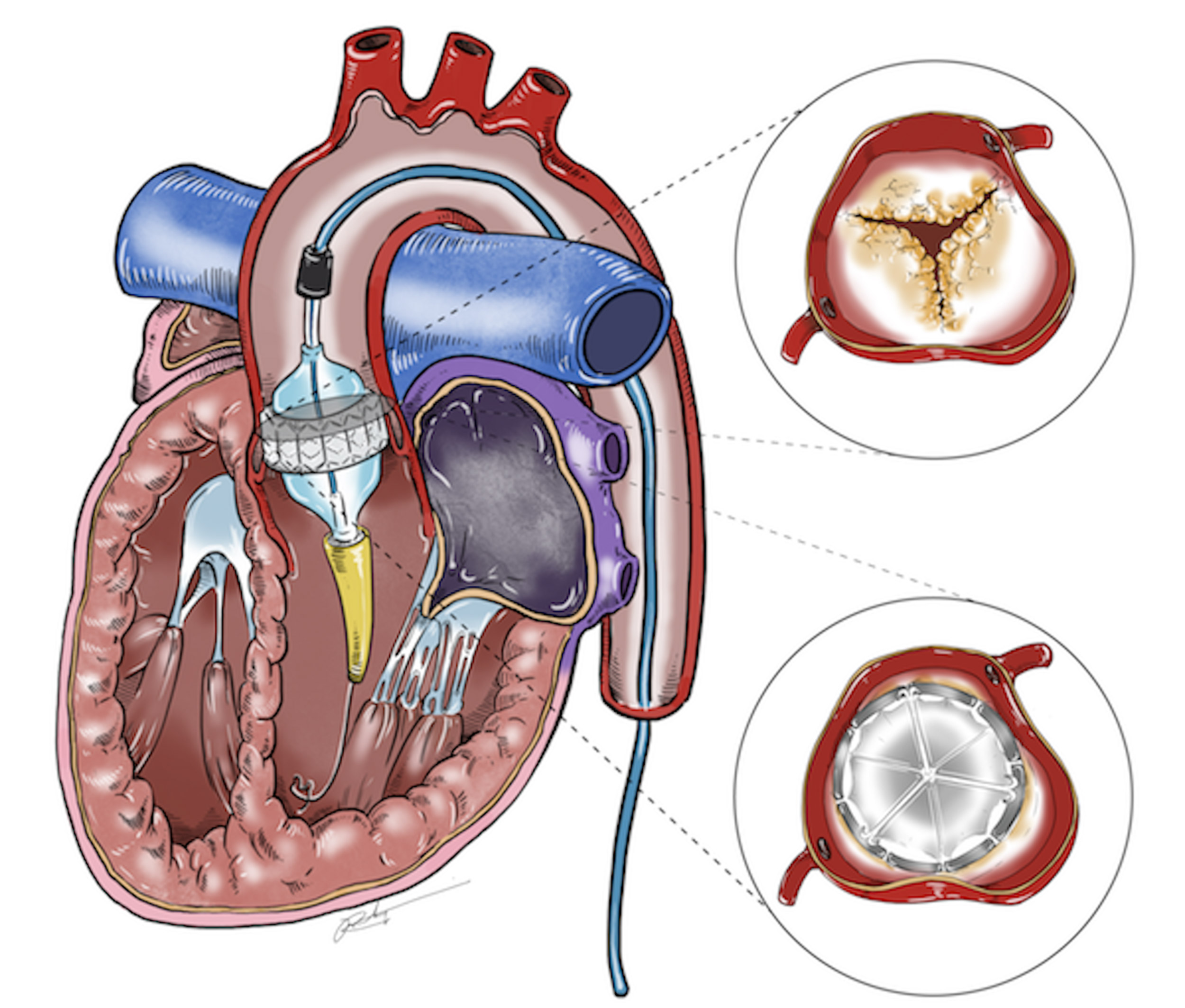

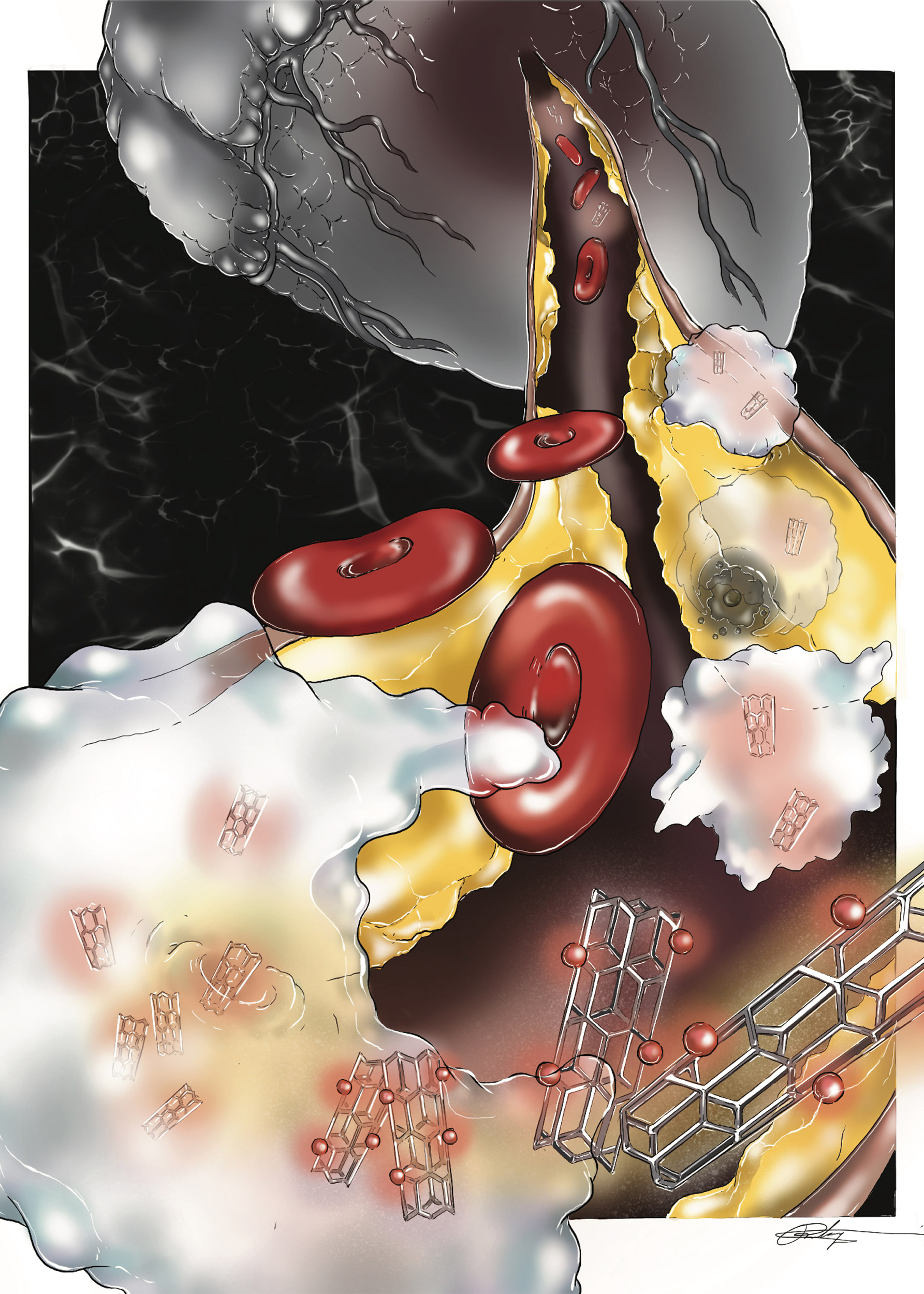

Orgill was also very supportive of Hamaguchi’s interest in medical illustration and she describes him as a “fantastic mentor.” With his support, her medical illustration career also flourished during that research year.

Orgill “created countless opportunities for me to illustrate my own papers, or illustrate other papers … in plastic surgery publications,” she said. “He was always very excited about the art and science intersection that has become a core part of my identity.”

From those first-published pieces and the connections she made in the hospitals, commissions and contracts started coming her way—all through word of mouth. Hamaguchi now has some 40 illustrations in her portfolio of paid and pro bono work, including research articles, journal covers, and book chapters.

While Hamaguchi can be proud of many accomplishments at HMS, building a career as a medical illustrator has been the most meaningful for her, she said, and a leap of faith beyond her comfort zone that cultivated a powerful proactive drive in herself.

“I came into med school with just that honors thesis project that I did at Stanford under my belt and very little else by way of professional experience, aside from my love for visual arts,” she said.

An ambassador of art, cultures

Plastic surgery residencies take approximately six to seven years to complete, and Hamaguchi foresees having less time to continue doing freelance medical illustration work during that time. But looking forward to the physician and surgeon she is training to become, Hamaguchi thinks she may be able to use her talents in the visual arts to communicate with patients and other health care workers.

Visual storytelling, she said, has the power to be used in patient care, by better informing patients facing complex reconstructive surgery about the care they will receive and the outcomes they can expect; in medical education, by better educating medical students and surgical residents on procedures; and in domestic and global surgery settings, as a way to remove barriers and improve access to reconstructive care for patients from different cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds.

“I think that what will give me the most joy is being able to use art in a much more practical way in plastic surgery and improving access to care and improving patient education,” she said.

When she completes her residency training, Hamaguchi sees herself having a clinical practice in the U.S. and traveling to Japan—to see her family members who have returned to the country, to catalyze the exchange of novel plastic surgery techniques between Japan and the U.S., and to serve as a mentor to young Japanese medical students, particularly female students aspiring to a career in surgery.

“I hope that I’ll still be connected and I can be an ambassador between the two countries,” she said.