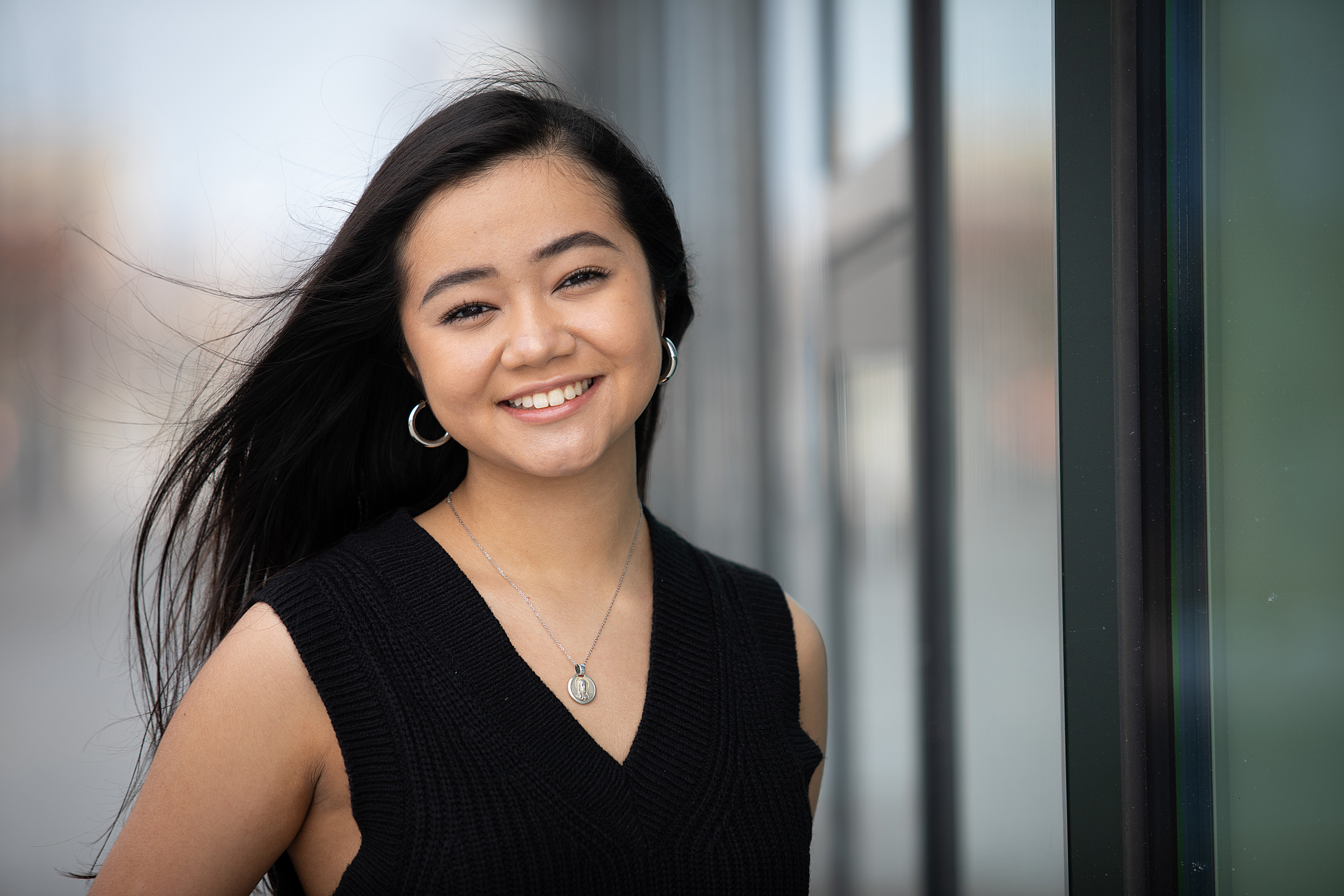

“Our perspectives as Hispanic engineers should be valued, uplifted, appreciated, and recognized,” said Daniela Villafuerte. “It is important to let people know that we are here …”

Eliza Grinnell/SEAS

Fueling a creative spark

Daniela Villafuerte tackles engineering challenges as she helps build a better world

This is one in a series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

As a child in Puerto Rico, Daniela Villafuerte ’21 was fixated on understanding how computers work. But the most advanced technology course offered at her all-girls high school was one in word-processing software.

Undaunted, Villafuerte began taking computer science classes at local colleges. Those classes introduced her to robotics, and despite having no experience, she decided to organize a competition team.

“We were the only all-girls robotics team in the competition, and we had to train on our own for a year to understand the process of how to build the robot,” she said. “It was tough in the beginning. We spent hours and hours in a classroom trying to figure out why the robot wasn’t moving or why it wasn’t lifting the ball it had to lift.”

The hard work paid off and Villafuerte’s team placed near the top in the competition, despite being first-timers. Their success inspired the school to add robotics to the curriculum.

Those experiences convinced Villafuerte to concentrate in electrical engineering at the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Finally, through her SEAS courses, she was able to learn how a computer works.

She also learned that engineering is much more complex than she had imagined. One of her most challenging, but rewarding courses at SEAS was “Engineering Problem Solving and Design Project” (ES 96). She and her classmates worked with the Harvard Global Health Institute and SaveLife Foundation to design a drowsiness detector that would alert a driver at risk of falling asleep behind the wheel.

“That fueled my interest in the intersection of health and technology,” she said. “Working on the signal processing team for that project, we had to understand the biological factors that were important, then translate those signals into a number that could be used to alert a driver that they should stop driving. It was very challenging.”

The support of her peers in the Harvard SEAS chapter of the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers (SHPE) helped Villafuerte persevere through complex problems in ES 96 and other technical classes. Inspired by the strong community, she served as SHPE president during her senior year.

Villafuerte and her fellow board members endeavored to create community-building events that would encourage Hispanic students. They also organized recruiting activities to help SHPE members achieve career goals.

“Our perspectives as Hispanic engineers should be valued, uplifted, appreciated, and recognized,” she said. “It is important to let people know that we are here, and to celebrate this community. And it is even more important to spread the word and tell new students about SHPE, so they don’t feel alone.”

She also found a like-minded peer group in the Harvard chapter of Engineers without Borders. Villafuerte joined as a translator, serving as a liaison between Harvard students and residents of the community of Los Sanchez in the Dominican Republic.

But her curiosity soon got the better of her, and as the EWB students worked to develop a water distribution system for Los Sanchez, Villafuerte took a hands-on role in a civil engineering project that was a bit out of her comfort zone.

“When I joined EWB, I didn’t know I was going to understand how a well is drilled, or what goes into a global stability analysis, in both English and Spanish, but it was a great experience for me,” she said. “We do all this analysis, but then when you get to travel to the community and see that those numbers are being used to create a water distribution system for a community in need, it really emphasizes that you are actually touching lives.”

Villafuerte wanted to explore other ways her technical abilities could make an impact, so she applied to the Undergraduate Technology Innovation Fellows Program, jointly offered by SEAS and the Harvard Business School.

She and a team of fellows conceptualized a startup that would use biodegradable material technology developed at Harvard to manufacture novel packaging that could replace single-use plastics.

“This wasn’t just the nuts and bolts of code. We had to manage a team. We had to figure out how to translate this technology and apply it to be a real-world thing. That fellowship helped me to be much more innovative,” she said.

She’s applied that innovative spirit to her senior thesis project. While stuck in lockdown in Puerto Rico over the summer, Villafuerte drew inspiration from the pandemic that was worsening all around her.

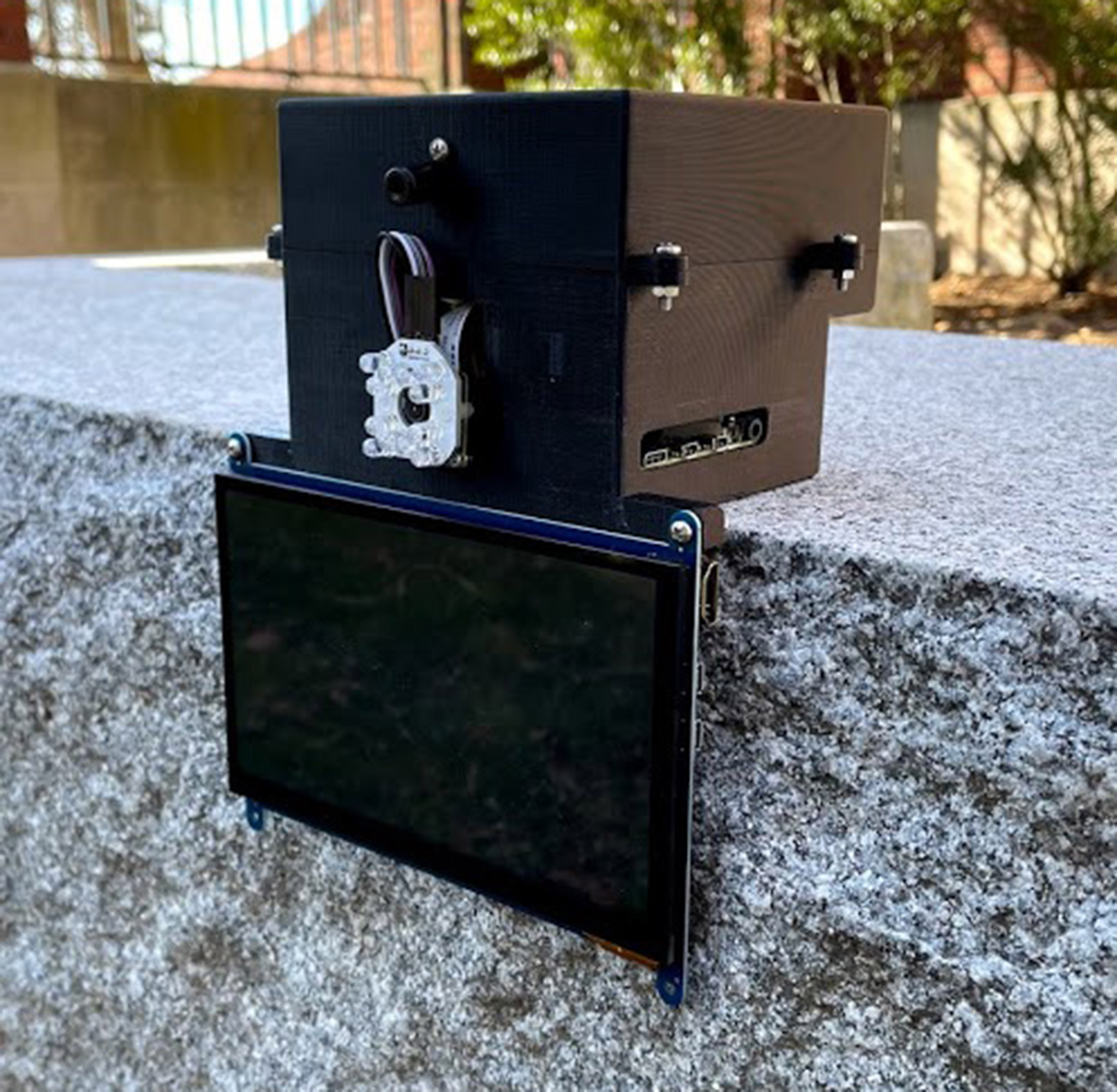

She and her partner set out to create an automated, non-contact health screening system to measure vital signs related to COVID-19.

Daniela Villafuerte stands near drilling equipment that was used during an Engineers Without Borders trip to Los Sanchez in the Dominican Republic. Villafuerte takes a bow (fourth from left) after a successful performance of “West Side Story.”

Courtesy photos

“When I was back home in Puerto Rico, you’d go into a store and an employee would measure your temperature with a temperature gun,” she said. “Our automated system is intended to eliminate the risk of exposure for that employee, but also add more data to provide better clearance.”

For instance, while temperature is used as a key factor to determine whether someone may be suffering from COVID-19 symptoms, it is not a very specific measure. Their device will track respiratory rate, heart rate, and oxygen saturation, all through non-contact methods, to provide a more complete picture.

Since she began working on the project at home, far away from the 3D printers and laser cutters in the SEAS Active Learning Labs, Villafuerte had to get creative to prototype — she ended up using Legos to build the initial structure.

Hands-on engineering problems have fueled her creative spirit, but so have the extracurricular activities she’s been involved with. An avid dancer since childhood, Villafuerte has danced with hip hop, jazz, and ballet troupes on campus, and also performed in the Harvard-Radcliffe Dramatic Club production of “West Side Story.”

“It was a great outlet for me to express myself,” she said. “For me, dancing has always been a way to communicate without words, to express myself through music and movement, and just be purely creative.”

Looking to the future, she’s excited to apply her creativity and problem-solving skills to a brand new set of challenges at a management consulting firm in Boston.

“The students and the community at SEAS have been very supportive and intellectually motivating. In my engineering classes, they were always so collaborative, and by working together and struggling together you make the best friends and find the best mentors,” she said. “The community really shaped me in a way.”