A taste of the old normal

Pilot project on hybrid classes offers insights into possible scenarios — and proves a delightful reminder of the joys of in-person learning

Nathan Reiff conducts Harvard Glee Club members in Andrew Clark’s hybrid music class.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Sam Marks felt almost giddy. It was the first time the senior lecturer on playwriting had taught in person since last March, and he couldn’t stop grinning at the handful of students looking back at him.

“I just want to sit here and look at you all,” Marks said to them. “This is what it’s supposed to be.”

Since the start of April, about 200 students, faculty, and staff have been taking part in a monthlong, in-person-and-virtual hybrid learning pilot for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. The test run involves 14 courses, ranging from the humanities to the sciences, that meet on campus and in person in Harvard Hall, Farkas Hall, or in tents in the Yard.

The students and professors in each course meet one to three times in person before going back to their online Zoom format and are part of Harvard College’s planning for the fall semester. The pilot is meant to give faculty, instructional staff, and students a sense of what it’s like to physically be in a class with coronavirus restrictions in place and then have to make accommodations for possible hybrid learning scenarios.

“We are still planning for all possible scenarios for the fall although we have a clear intention of doing as much in-person learning as we can,” said Rebecca Nesson, associate dean of the Harvard College curriculum. “We’re out of practice doing a whole bunch of things and have a lot of systems that need to get restarted. We’re trying to get all of those things going and fold in the extra procedures [like social distancing] that we have in a pandemic.”

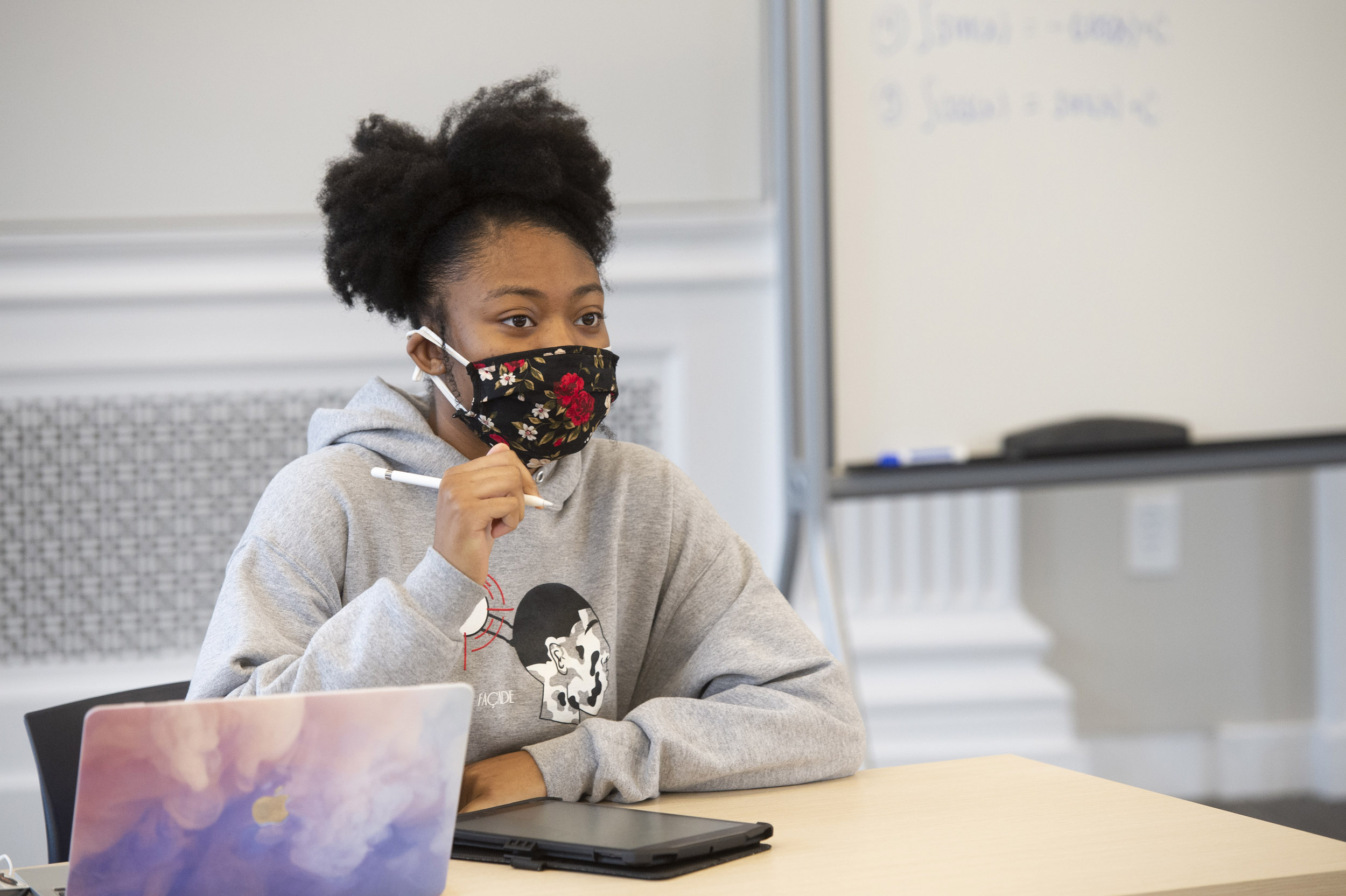

Susan Takang ’24 asks a question during a math class being taught by Reshma Menon.

The Office of Undergraduate Education set up two classrooms for hybrid learning in Harvard Hall. One was renovated before the pandemic for this purpose, and the other has a portable cart with all necessary equipment. Both rooms are outfitted with camera and audio equipment so students working online can see and hear what is happening just as well as can students sitting inside the classroom. In-person students also sign in online so they can interact with their remote classmates.

This was the format for a history course co-taught by Daniel Lord Smail, Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of History, and Matthew Liebmann, Peabody Professor of American Archaeology and Ethnology. About 10 students were spread out in Harvard Hall 101, while close to 40 watched on Zoom. The Zoom screen of remote students was displayed on big-screen TVs in the classroom.

The class went smoothly for the most part, but Liebmann, who was teaching from home, was quick to point out when something wasn’t clear for the online audience, such as when the PowerPoint was not being shared or when the remote cohort did not have a clear picture of the small artifacts the in-person students had examined. In the classroom, Smail was able to address the issues quickly and made notes for future improvements to ensure both sets of students had access and involvement.

“On several occasions I said something along the lines of ‘Let’s turn to the Zoomies now’ and Matt would call on a few names while I looked at the camera, then back to roomies,” Smail said. “That seemed an important way to make sure that all students felt they were getting equal attention.”

What’s been most salient from the pilot is the excitement shared by both the students and professors who were able to resume in-person learning, even for a short while. For the first-years, it marked their introduction to a college classroom. For juniors and seniors, it felt like a return to normal. For one third-year law student enrolled in an undergraduate course, it was likely the last time he’d be in an in-person class. Many students took selfies to celebrate the moment.

Even once-awkward icebreakers were met with fresh zeal. “I’m excited to meet you all in person instead of on a screen,” said Michael Yin, a junior introducing himself to the playwriting course before admitting the fun fact that he hadn’t worn contacts since the pandemic started.

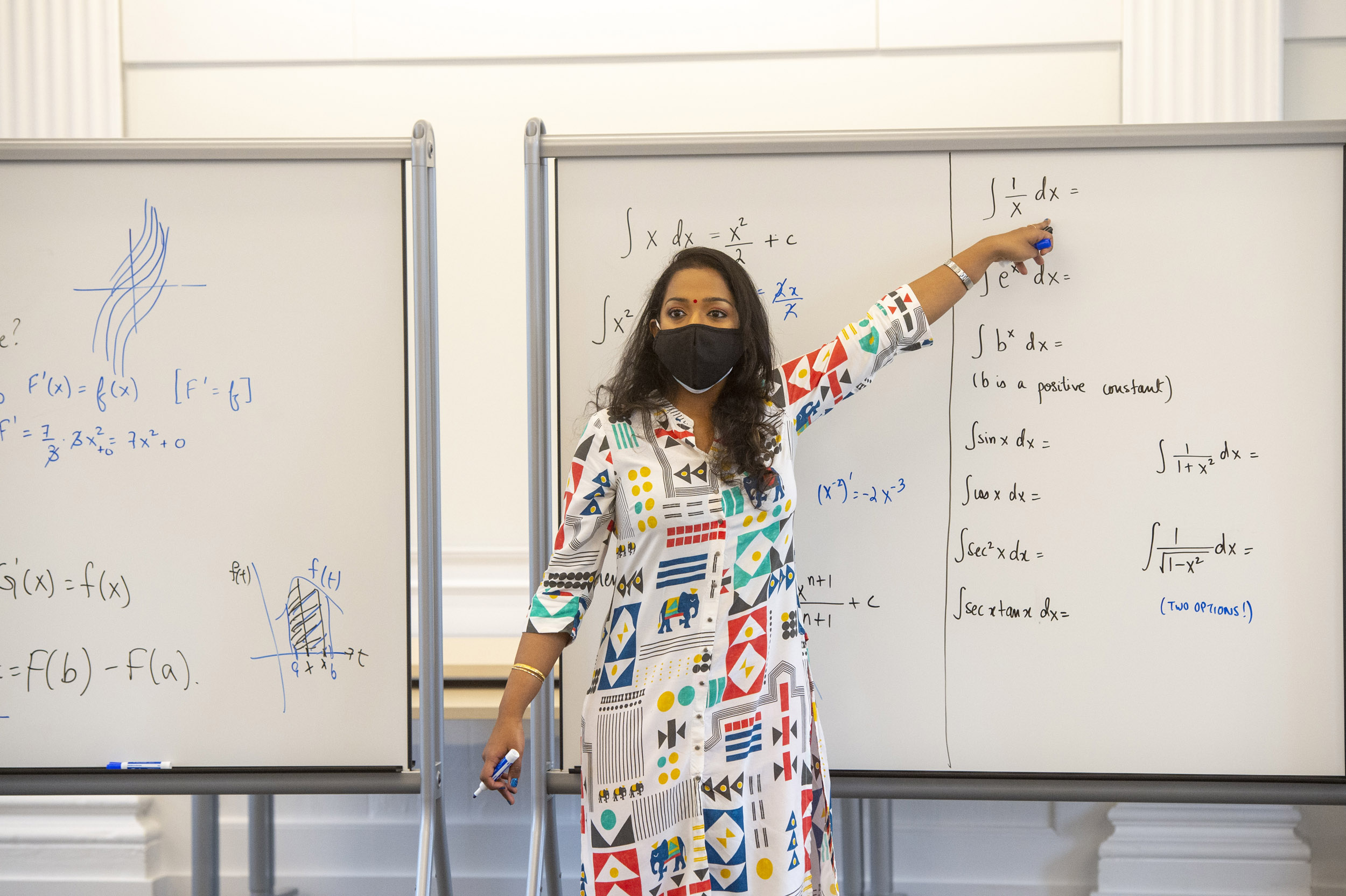

Preceptor in mathematics Reshma Menon stayed after class to answer questions from students and meet those who just wanted to formally introduce themselves in person. She said she missed these “organic” moments and how engaging in-person learning can be, especially in a subject like math.

Juan Espinoza, a third-year Harvard Law School student, joins others in a tent in the Yard for English with instructor Sam Marks.

A group of first-years in her course agreed. “I felt like I learned better this way,” said Kira Fagerstrom.

Jasmine Adams added: “It was a significant difference in being able to pay attention. Everything just felt more clear.”

“I could immediately ask her, ‘Oh, what did you mean by that?’” added Taina Rico. “On Zoom, sometimes you don’t want to interrupt.”

They all came to the same conclusion. The course left them wanting more.

“This reassured me that there’s so much more to the Harvard experience,” Adams said. “This is exciting for when we actually have all of our classes like this. This is what we have to look forward to.”

Getting to in-person pilots involved a host of logistics, from determining the proper scale of classes to test to recruiting faculty and teaching staff volunteers to participate to scheduling to working with Harvard University Health Services to determine COVID testing and monitoring procedures. The in-person courses were open to faculty, teaching staff, and students who lived on or near campus. Each class has an observer from the College taking notes on how it went and ensuring proper social distancing procedures were followed. At the end of each class, students, faculty, teaching fellows, and the observers complete feedback surveys on the experience.

Each of the courses is meant to address a specific question about in-person or hybrid learning. Questions include: How does social distancing affect lab classes where equipment often has to be shared? Does mask-wearing affect learning in a foreign language class where lip movement can be crucial? And how do masks affect performing-arts courses like Glee Club?

“We want the education that we offer in the fall to be as in-person and as excellent as it can be,” said Nesson. “Perhaps our fondest hope is that this isn’t necessary at all because by the time it comes around, we will all be able to be together in classrooms with none of these constraints on us. But we need to be ready in case those constraints are in place.”